Abstract: The hero archetype has two sides. On the one hand it provides the impetus for personal emancipation, contributing to the success of Western culture. On the other hand it has given rise to present-day hubris and expansionism. The article investigates the dark side of unthinking heroic worship. It is argued that our civilization is under the

spell of an illusion of heroism causing a collective hubris and fixation on

principles, to the detriment of the personal values of the heart. As portrayed

in myth, the hero must be allowed to die.

Keywords: sun-hero,

suicide bomber, terrorism, Icarus, hubris, individuation, apocalypse, millenarianism, Carl Jung.

Introduction

Western civilization unwittingly

suffers from an obsession with the hero archetype, invoking a collective hubris.

The hero theme is depicted in the myths of Icarus (Wiki, here),

Bellerophon (Wiki, here),

and in the thematic

‘death of the sun-hero’ (cf. Lang, 1894, here). An Icarian heroism permeates culture. It implies an

obsession with daylight consciousness and its values, which causes the

irrational burgeoning life of the unconscious to be burnt off. The scourging sun

melts away the wings of Icarus so that he comes crashing down. A lightning

from Zeus makes Bellerophon suffer the same fate. The ideal is to go faster and faster, higher and

higher, to achieve expansion at all cost. There’s a relentless search after career, money, and

status. Few people listen to the faint voice of the spiritual unconscious,

anymore. Instead we tend to become obsessed with the Icarian premises of career, social

adjustment, political correctness, and scientific advancement.

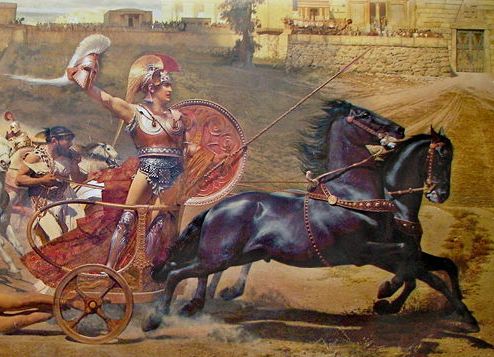

Detail from

Triumphant Achilles by Franz von Matsch (Wikimedia Commons).

The dragonslayer in the Nibelungen saga,

Siegfried (Wiki, here), represents an archaic side of the psyche, belonging to the

Nietzschean fantasies that reside in the unconscious. He is the hero that

extraverted men like to emulate. They want to be famous, brandishing their

sword in the sun, in order that everybody, especially the women, may see how splendid

they are.

What complicates matters is that the sun-hero suffers a violent death, as do Icarus

and Bellerophon. It depends on a secret identity between the sun-hero and the

chaos-dragon. The latter is the mother of the hero, from which the hero derives

his power.

In Egyptian myth, the sun replenishes its strength during the

nightly journey in the underworld, and rises as a newborn from the darkness of

chaos. During the nightly journey the dragon Apophis is defeated; yet the destiny of the sun

god Ra is to again suffer demise in red blood at the western horizon.

The twin gods Cautes and Cautopates, in Mithraic religion, each holds a torch. The one points upwards, the other downwards.

The Hero is always accompanied by his dark twin, the sinister Shadow — like Sherlock and Moriarty, Frodo and Gollum, Siegfried and Hagen, Horus and Seth, Christ and Satan. The one is destined to heaven and the other to hell. If one identifies with the Hero, then one is bound to be stabbed in the back by one’s own Shadow.

Heroic possession

The heroic obsession has made an

inroad in the Muslim world. The suicide bomber symbolically attacks the chaos

dragon, but he also kills himself in this act, in conformity with the

dramaturgy of the hero archetype. Western societies accommodate suicide bombers

who are intent on killing the “dragon” who is their own mother, and who

generously has fed and raised them, namely society, as such. These people are

possessed by the sun-hero archetype, because they are lacking in the capacity

of a strong consciousness, which would allow them to carry such ideas responsibly,

instead of living them out in archaic form.

Muslim young men blow themselves away in their “heroic”

quest against “draconic evil”, whether it’s the United States or a competing Muslim

denomination. They want to achieve glory at all cost. Thus, who or what happens to

be chosen as “dragon” is of little consequence. The gist is that they

have a sincere wish to be glorious dragonslayers.

There was even an attempt to build a whole civilization on the

heroic theme, namely the Third Reich. The “backstabbing myth” involves “the

Jew”, representing chaos, who stabs the heroic German soldier in the back (see

propaganda image

here).

According to this myth the WWI army had remained “undefeated in the field”,

only the revolution at home was to blame for Germany’s defeat.

Accordingly, in the Nibelungen saga, the sun-hero Siegfried was

stabbed in the back by Hagen. This image is what underlies the backstabbing

myth. It is a projection of an archetype: the hero, in defeating the dragon,

is himself dealt a deadly wound. When the dragon is defeated, the hero’s own fate

is sealed. Germany, who lived the sun-hero myth and attacked the forces of chaos

in the form of the “inferior races”, also doomed itself to

destruction. Thus, Siegfried is his own shadow, his own “Ugliest Man” (Nietzsche).

The heroic possession causes destruction to the Muslim world, the

Muslim religion, and in increasing measure the Western world. Such people have in

mind to kill the chaotic forces of the unconscious. Accordingly, they aim to remove any sign

of the spontaneous from religious or daily life. The politically correct ideology

of Western countries has much in common with this programme. It implies a fixation

on

principles of consciousness: any signs of burgeoning life originating in

the heart and the unconscious soil must be rooted out from society. For

instance, one of the foremost hubristic moral principles is that mankind must be

maximized on this earth. The world’s poor must be sustained at all costs,

without regard to environmental damages.

Life must be adjusted to political correctness and the conventions of

tidiness. Likewise, the ideal of political Islamism is a tidy society

adhering to perfect rules, under the antibiotic rays of a scorching sun, which

allow no room for spontaneous life. Many in the Western world live according to

The Principles, whereas the Islamists have already found the definitive

truth in the Quran. Such people will not allow room for the unconscious,

equal to a dragon’s nest full of treasure. As a consequence radical Islamism is today inadvertently

involved in the self-destructive dynamic of the sun-hero.

Extraversion

and worldliness

Carl Jung (Wiki, here)

was at least as controversial as the Freudians in exposing the Nietzschean

fantasies residing in the unconscious, such as the Aryan hero Siegfried. Says Jung, “As early as 1918 I wrote:”

As the Christian view of the world loses its authority, the more menacingly will the “blond beast” be heard prowling about in its underground prison, ready at any moment to burst out with devastating consequences. [‘The role of the Unconscious’, orig. published 1918.]

It hardly requires an Oedipus to guess what is meant by the “blond beast.” I had an idea, however, that this “blond beast” was not restricted to Germany, but stood for the primitive European in general, who was gradually coming to the surface as a result of ever-increasing mass organization. (Jung, 1978, p. 227)

This realization

remains intolerable to this day, due to the fact that Siegfried the sun-hero is a specter from the

archaic psyche. Thus, to become like him, and take part in his shining

glory, is today unwittingly an obsessive ideal. It sometimes acquires ludicrous proportions, when the

human dimension is lost. It is what motivates Brad Pitt when he makes the campy impersonation of

Achilles in the film “Troy”. It is what drives

Julian Assange, and Silvio Berlusconi, too. They all claim to be

idealists, i.e. having artistic or moral incentives. However, this is merely

a screen because they are all obsessed with the Nietzschean hero archetype. Look how

preoccupied extraverted Americans are with the heroic theme in their Hollywood

productions. It has cultic dimensions. The problem is that the hero is portrayed as immortal. Traditionally, he always dies in the end, which is proper.

Carl Jung, for his part, recounts how he “killed” Siegfried

in an ambush, as part of a dream. If he didn’t understand the dream, he would

have to shoot himself, a voice said. He had no other choice than to kill his worldly, ambitious,

power side (Jung, 1989, ch.VI, except here).

An introvert, as Hagen in the Nibelungen saga, is capable of killing Siegfried,

but an extravert cannot. It is experienced as a crime beyond comparison, and therefore

such a thing is unthinkable to an extravert. Thus, to claim that such

archaic ideas and obsessions exist inside each and everybody, is a greater insult to the

extravert’s sentiments than to say that we are all driven by sexuality, on

Freudian lines.

The hero’s journey is viewed as the pattern of individuation

(Wiki, here)

in our culture. But the myth always involves the death of the hero,

something which tends to be forgotten. Since the hero must die but life must continue,

the hero is not the perfect model of individuation, if we aren’t intent on following

in the footsteps of suicidal Sturm und Drang romantics, or Islamic suicide

bombers. Unmindful identification with the hero archetype is likely to lead

to catastrophe as the archetype poisons the soul with an expansive spirit. Although this

fulfils a purpose in that it fuels the flight from mundane dependency, the hero is doomed to

fall prey to Mother in the end, since he is surreptitiously dependent on her.

Erich Neumann (Wiki, here) dwells long upon the

topic of the tragic hero, which he names the “struggler” type (cf. Neumann, 1995, pp. 88-101).

In fact, all heroes are strugglers. It is only that the tragic versions, such as Adonis, Narcissus, et al.,

stand out as more plain examples. The death

of the hero really implies that he must be abandoned as a role model, because heroic

expansionism will lead to catastrophe. Our Icarian culture flies on infirm wings, as

the latest financial crisis bears witness to. Heroism has had an impact on the

Jungian psychoanalytic movement, too. Joseph Campbell (Wiki, here) views the hero’s journey as a blueprint for

individuation. Perhaps this evaluation is not entirely fair as he relies heavily on

myth and not on his own concepts. Still, true to his American heroism, he has popularized

the concept of life as the “hero’s journey”. Psychologist Edward F. Edinger

is clearly heroic in his worldview (cf. Winther, 1999, here).

Although the Freudians recognize the Oedipus complex, it is viewed as a mere infantile

pattern, despite the fact that Oedipal heroism permeates our whole culture.

The hero’s death

Heroic identification imparts a buoyant

capacity on the ego. But this is unneedful if consciousness has developed in strength

and is already anchored in ‘terra firma’. The hero archetype fulfils a purpose in the

juvenile and immature personality, allowing deliverance from psychological

dependency (the maternal bond). In the Arab world, and in the Third World generally, people have always

existed in collective identification, remaining unaware of linear time, instead

retaining archaic “circular time”. On

account of ongoing changes in the world (the emergence of the Internet, especially), the oblivious

lifestyle is undermined.

How can the psyche cope with these developments? There exists an

instinctual incitement to develop an autonomous ego. As the hero archetype

emerges like a sun from the netherworld, young men tend to identify with it.

Overwhelmed by its numinous intensity, the ego is too weak to relate to

it, with the consequence that personality is incapable of diverting the

heroic energy into personal improvement. Like Don Quijote he

will attack any “windmill” that can be identified as the dragon, thus extinguishing himself. What could be the beginning of individuation, turns negative due to the workings of archetypal identification.

The hero’s journey is not simply a blueprint of individuation. It

is associated with the rise of consciousness proper. However, if the conscious increase is to be

maintained the hero archetype must die and sink back into the dark. The

result is that the conscious accretion, which the heroic archetype brought with

itself, may remain in the egoic realm and strike down roots there.

Personality has then reached a higher plateau of awareness and discernment.

In order, then, for the heroic archetype to be effective, it must

die. The mythologem of the hero’s death is not only present in the Passion of

Christ, but is very typical for the heroic tale. Identification with the hero

has the tragic consequence that the heroic mythologem is copied to the bitter

end, which results in untimely death. As physical death definitely puts an end

to individuation, the hero mythologem cannot easily be equated with the ego and

its journey toward maturity and independence. This equation is too simplistic.

The hero is better viewed as an archetype, and not as a personal ego. Yet, many authors, including Neumann and Campbell, tend toward a personalistic understanding (cf. Winther, 2009, here).

It is high time to abandon heroism, since it also takes a toll on social

relations. An intelligent interchange is impaired if some people are expected

to carry the heroic mantle while others are expected to cringe to the hero. Freud

and Jung are subject to hero worship in a way which takes on ludicrous

dimensions. People read Jung’s autobiography time and again, and presently The Red

Book, a diary of his unconscious exchange, attains surprisingly high sales

figures (cf. Winther, 2007, here).

Why all the fuss? I suspect that many people expect to find a

blueprint for individuation in Jung’s personal journey. The hero is projected on

Jung despite the fact that he himself expects people, as adults, to stop

following role models, since this is an attitude associated with the juvenile period.

Living according to a role model can have a secondary damaging effect in that

the person identifying with the hero figure, while he tries to emulate the master, is unable to find the path

suitable for himself. Jung often returns to the problem of ‘Imitatio Christi’, when people in history have attempted

to live the life of Christ instead of following a path of their own. It can’t be

a much better idea to imitate Jung.

People should be rooted in their own soil instead of living according

to a pattern copied from a hero figure. Look at the forlorn figures roaming

about in Hollywood trying to become film stars. In a TV documentary, certain of them appeared like empty shells. To be “famous” is

really the red herring of modern life; it diverts the attention from the inner

soil, the ‘prima materia’ in which true individual life grows. I maintain

that hero worship, including impulsive hero identification, causes damage to

individuation, corrupts relations, impairs the development of personality, and

ultimately puts our whole civilization in jeopardy. The way in which Western civilization has self-destructed on two occasions has to do with heroic identification. Recently, Western civilization has taken upon itself the role of Saviour of all the hapless people of the earth — again with horrible self-destructive consequences. Yet, Jesus of Nazareth, contrary to modern Christian practice, insists that one shouldn’t involve oneself with problems that aren’t one’s own. It’s good enough to put in one’s two pennies. Pull your own weight, he says. Carry your own cross!

Conclusion

My argument is that our whole culture is

heroic in type. It is overly expansive, irrepressible, effervescent, unconstrained,

unruly, and titanic. The Western population suffers from a cultural megalomania — they believe in the glorious future of our civilization and that we are

soon going to conquer outer space. People have forgotten about the demands of

the unconscious, the Earth-Mother, and instead put their trust in technology

and science. Christian religion tried to put a curb on the expansive spirit with

the message of an imminent catastrophe, the apocalypse. Since the time of Jesus,

a dark cloud has brooded over the heads of people. A catastrophe has been

looming, when Icarus’s wings fall off, heroic mankind plunges

into the sea, and the Last Judgment is invoked.

I reason that the

apocalyptic sentiment, on the personal level, serves the purpose of

compensating for the tendency of taking to the air, like Icarus. The “pillars”

of our civilization, that is, Jesus, Plato, and St Paul, advocate a frugal

lifestyle. They are antagonistic toward a “Western” (esp. American)

lifestyle of career, material wealth and success. In agreement with this, they

all had an apocalyptic outlook: “the kingdom of God is nigh at hand”, and

“the Second Coming is nigh”. Plato, for his part, had a vision of the destruction

of Atlantis, and the subversion of Athens. He also presented the first

anti-hero, namely Socrates. Another ancient master who advocated an unassuming

lifestyle, and detested all forms of expansionism, was Chuang-tzu (Wiki, here).

Since

the Age of Enlightenment the compensatory apocalyptic sentiment has abated.

As a result, mankind today is flying too high. Compensations are still occurring

in people’s dreams, where different versions of the Icarian fall take place, such as earthquakes and large buildings collapsing. Such images probably work to transform the

expansive energy to something unfeigned and profound in personal life. In

the fine arts, “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus” has been very

popular, fulfilling a compensatory purpose. Millenarian fantasies fulfil a

function as long as expansive heroism is overestimated in the public mind.

Apocalyptic compensations, and the ‘death wish’ of the hero, will abate when people abandon heroism. Arguably, a

restoration of the above “pillars of our civilization” can accomplish

such a change of heart.

Landscape with the fall of Icarus, by Joos de Momper the Younger (1564-1635).

Nationalmuseum, Stockholm (Wikimedia Commons).

Hero identification fulfils a function in human life, but at some point it’s time to abandon the Icarian madness of flying higher and higher, faster and faster. This is important also on the personal level, if the individual is to reconnect with Mother Earth. The Earth contains nourishment for the soul, in the simple things, the earthly contents of the unconscious.

© Mats Winther (February 2011).

References

‘Bellerophon’. Wikipedia article. (here)

Campbell, J. (1972). The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton University Press (Mythos).

‘Carl Jung’. Wikipedia article. (here)

‘Erich Neumann’. Wikipedia article. (here)

‘Icarus’. Wikipedia article. (here)

‘Individuation’. Wikipedia article. (here)

‘Joseph Campbell’. Wikipedia article. (here)

Jung, C.G. (1978). Civilization in Transition. Princeton/Bollingen.

-------- (1989). Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Vintage.

Lang, A. (ed.) (1894). The Yellow Fairy Book. Electronic version. (here)

Neumann, E. (1995). The Origins and History of Consciousness. Princeton University Press (Mythos).

‘Nibelung’. Wikipedia article. (here)

Palmer, M. & Breuilly, E. (transl.) (2007). The Book of Chuang Tzu. Penguin Classics.

Winther, M. (1999). ‘Edinger – the ego-prophet’. (here)

-------- (2007). ‘Dependency in the

analytic relationship’. (here)

-------- (2009). ‘The real meaning of the motif of the dying god’. (here)

See also:

Winther, M. (2006). ‘The psychodynamics of terrorism’. (here)