The real meaning of the motif of the dying god

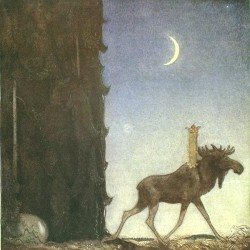

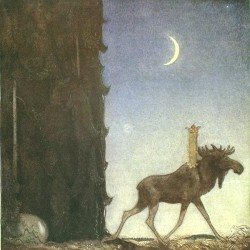

Princess Cottongrass, by John Bauer

(images are public domain)

Abstract: Narcissus, and other tales, have been abundantly

used in concretistic types of psychological interpretation. The article shows

that they ought to be viewed in abstract terms as portraying processes in the

individual and collective psyche. The examined stories depict the mystery of

incarnation, symbolic of the emancipative effect of conscious

realization. The gender of the god is discussed, and it is argued that the

dominance of the masculine divinity depends on natural processes of conscious

enhancement.

Keywords: archetype, Princess Cottongrass, Coyote Blue, Narcissus, Unicorn, Christ, Lucifer, Oedipus.

IntroductionFreud viewed dreams as disguised

wish-fulfillments. It isn’t workable as a general dream theory, since it

isn’t universally applicable. According to a modern view, corroborated by neuroscientific

research (cf. Solms, 2004), dreams aren’t hiding

anything — rather,

what you see is what you get. Myths and dreams would better be analyzed

in terms of

archetypes, that is, more in the way of abstractions. It’s

easy to understand why. For instance, if we argue along with Freud that an image signifies the male genitals, it means to pin down the image and to jump to conclusion. It is better to argue that it is ‘phallic’ in character, which is to reason in a more

tentative and tactful way. Thus, we

haven’t shut the door to the dream, but may continue relating to the image. We

aren’t ready with it, yet, because it is a

symbol that cannot be deciphered like a code. Symbols are difficult

and multi-faceted. They elude the linear intellect, as they represent a

form of non-discursive thinking. If a content is said to be “disguised”,

hidden behind the dream image, then the dream is effectually devaluated. It’s

tantamount to trashing the dream image. As such, it has no value, since it is

regarded as a mere screen.

One would better keep to the dream image and

circulate around it, even extend it. It represents a positive attitude

toward dreams and mythical content. The “disguised

content” theory, on the other hand, is depreciatory. It harms the relation to the unconscious. That’s why we ought

to stop thinking in terms of disguised content, which is a harmful method by

which a dream is immediately understood in concretistic terms. By example, should

one dream about a giraffe, then the dream means a giraffe. The meaning hinges on

the symbolic quality of the dream content. It is indeed a wild and long-necked animal, living

on the dark continent. But it does not imply a cloaked genital

content. It is better to say that the dream image has a certain phallic quality

to it. That’s what the dream wants to say: an entity exists, which is not a male

organ, yet is certainly phallic in some sense. It doesn’t necessarily point at

sexuality, but is probably in some sense coupled with instinctuality.

Alternatively, it could mean the

eros principle. After all, the phallic

aspect is only one aspect of the giraffe dream. Although there are cases where

dreams appear almost like wish-fulfillments, they generally relate to the wholeness of life. Thus, they may also point to spiritual content.

M-L von Franz says:

In many so-called Jungian attempts at interpretation, one can see a

regression to a very personalistic approach. The interpreters judge the hero or

heroine to be a normal human ego and his misfortunes to be an image of his

neurosis. Because it is natural for a person listening to a fairy tale to

identify with the main character, this kind of interpretation is understandable.

But such interpreters ignore what Max Lühti found to be

essential for magical fairy tales, namely, that in contrast to the heroes of

adventurous sagas, the heroes or heroines of fairy tales are

abstractions — that is, in our language, archetypes. Therefore,

their fates are not neurotic complications, but rather are expressions of the

difficulties and dangers given to us by nature. In a personalistic

interpretation, the very healing element of an archetypal narrative is

nullified. (1996, p. viii)

She is referring here to a regression to a Freudian personalistic

view. The Narcissus myth, as such, has no bearing on the pathology of

narcissism. Although the myth is suitable as a metaphor when discussing narcissism, it does not mean that we can make scientific

conclusions drawing on the myth. We may only use it as an illustration. For

instance, say a person is enveloped in his own misfortunes of the past. In that

case one can draw on the saying that

“it is no use crying over spilt

milk”. But one couldn’t write a psychological article, discussing the

qualities of milk, and make scientific inferences from this. We mustn’t discuss

homogenized milk versus pasteurized milk and, from this, make inferences as to

patient pathology. In that case we are putting the cart before the horse. Yet, this type of error is committed again and again in psychoanalytical interpretations.

The Swedish fairytale of Princess Cottongrass has

become slightly famous in psychoanalytic circles, being cited in journal

articles and books. True to tradition, it is undergoing pathologization

by various authors. The following summary is derived from Kjellin’s adaptation of the original folk story. Cottongrass

makes a more authentic impression than the Narcissus story. Judging from

elements in the fairytale, and its naive accuracy, it is quite possible that

it has emerged independently of the Narcissus story. It has elements in

it that are lacking in the Greek story.

Leap the Elk and Little

Princess CottongrassPrincess Cottongrass was full of love: “I am young and warm. I have warmth enough

for everyone and I want to share the good I have.” She wishes to leave

Dream Castle, where she lives with her mother and father.

She sees an elk, Long Leg Leap, and asks him to take her out into the

world. He cautions her of the difficulties, but she insists. Soon Princess Cottongrass rides away from Dream Castle on Long Leg Leap’s back. He cautions her not to let go of his

horns, and not to speak to a band of elves that will attempt to confuse her. The elves appear and

ask her numerous questions. Then her crown starts to slip away, and she

lets go with one hand to grab it. That is enough for the elves to snatch away

her crown. The elk warns her again, and tells her that she was lucky that time.

At night he watches over her as she sleeps. But he is seized by a longing

to do battle and a desire not to be alone anymore.

The next day, with the princess on his back, he races into the forest. Fortunately, he manages to restrain himself and slow down. Again he cautions her not to let

go of his horns, this time when a witch questions her. But as her dress begins

to slip away, she reaches for it and the witch grabs it. He tells her how lucky

she is; if she had let go with both hands she would have had to go with the

witch.

All along, the elk is getting wilder, wanting to run and mate without

restraint. He manages to control himself, with difficulty, and soon carries the

princess to his very special place; a pool. He cautions her not to allow the

heart she wears around her neck to fall off. Sure enough, as she looks into the

pool, the golden heart her mother has given to her slips off her neck. It falls into the water’s

depths, and she cannot retrieve it. She insists upon staying at the pool, even

though the elk asks her to leave. Princess Cottongrass is enchanted now. She stays, gazing into the

water, searching for her heart.

Many years have passed. Still Princess Cottongrass sits and looks

wonderingly into the water for her heart. She is no longer a little girl.

Instead, a slender plant, crowned with white cotton, stands leaning over the

edge of the pool.

(See also fig.1. Adapted from Schwartz-Salant’s

summary (1982) of the story in Great Swedish Fairytales (1974). Images (reduced)

by John Bauer, as published in the same book.)

The archetypal fairytale characterIndeed, we are

here dealing with an unconscious archetype, which implies that it’s more of a generic pattern.

Whereas the orthodox Freudian would view Cottongrass in sexual terms, the

modern psychoanalyst discusses it in terms of narcissism. Others might

connect it with the

death drive, etc. There is no end to the plethoric

expressions of modern psychoanalysis. People use these stories to shed light on

their own standpoint, which means that fairytales are used as

metaphors. There

is nothing wrong in this, provided that it is remembered that they do not

represent mother nature’s own diagnosis of neurosis. Their applicability as

metaphors derives from their generic quality, i.e., their archetypal language. It

is time to bring this to a conclusion. The following is my understanding of

the underlying meaning of these stories.

Princess Cottongrass portrays

an unconscious content that has reached a high level of excitation, i.e., it’s

laden with energy. She has received a golden heart and is brimming with love.

Correspondingly, in Bohr’s atom model, an electron that acquires an energy

quantum, will reach a new excitation level and jump up to a higher orbit.

Accordingly, the princess leaves the Dream Castle (the unconscious world of

dreams) in a journey toward conscious realization. When an unconscious content

is laden with energy it is capable of breaking the surface of consciousness.

Comparatively, Narcissus is warned by the seer Tiresias that he must not become

conscious, as this will cause his demise. This is exactly what occurs to

both these figures; they pass the threshold of consciousness as they become

fixed to the image in the water. In this moment, they become self-conscious.

This represents the moment of their death, as they are then become integrated with

consciousness. Both fairytale characters are infixed in the ground as plants, and

strike down their roots in the soil. They have lost their autonomy and can no longer

roam about in the Dream Castle and its surrounding woodland. Thus, they have died and

passed the border to the other side — the conscious world.

The princess successively loses her regal insignia; her crown and her

dress. In the process of becoming conscious, she gradually loses her divine

stature as autonomous archetype. By the time she reaches consciousness she has

been reduced to a simple yet stable content. As a plant, it can be observed at

any time during the day, because it stays in place, just like any other content

that the ego has access to. Both she and Narcissus are flowers of colour white;

the colour of daylight consciousness. As plants, they lean over the water, able to see their own reflection, which is symbolic of the conscious condition. To

be conscious is to be able to see oneself. At that very moment one falls into

reality, and leaves the Dream Castle. Similarly, the god Dionysos fell into the world when he spotted his own image in a mirror.

Obviously, then, both Narcissus and Cottongrass are generic models in

that we cannot exactly know what characterizes the content that becomes established and rooted in

consciousness. It’s a mysterious process which is here portrayed. It could be

the realization of sexuality, or it could be awareness of the

anima.

Cottongrass could also be seen as a “dream” leaving the Dream Castle,

reaching consciousness, there to be remembered as a fine gift; a beautiful

flower. Indeed, Narcissus could even be seen as a minuscule version of the Christ. He is the son of a god (the river god Cephissus) who

enters worldly reality. Thus, he experiences death, fastened to the stem of the

narcissus flower, much like Jesus was fixed to the tree. According to a medieval legend, the Christ,

before the conception, is an unruly unicorn running rampant in the woodlands, similar to Narcissus the huntsman.

The fairytale viewed as mystery

The elk

symbolizes the benign aspect of instinctual unconscious nature, which helps

unconscious energy to integrate with consciousness. Other archetypes

oppose the journey of realization, and try to seize the princess (the witch;

the elves). But the elk, owing to his age-old wisdom, is cooperative and helpful. This, it

seems, is contrary to his own wild and impulsive nature (he wants to run off and

joust with other elks, and to mate).

What is here portrayed is really a great mystery. How come

unconscious instinctual nature cooperates to its own demise; to its gradual

integration with consciousness? We don’t know why the elk does this. The Lucifer

myth is the cosmogonic version of the same motif. Lucifer, as the most beautiful

and shining of the angels, has attained a great

excitation level,

and this is what precipitates his fall. John Milton, in

Paradise Lost, describes his

descent:

And now a stripling Cherub he appears,

Not of the prime,

yet such as in his face

Youth smiled celestial, and to every limb

Suitable grace diffused; so well he feigned.

Under a coronet his flowing

hair

In curls on either cheek played; wings he wore

Of many a coloured plume sprinkled with gold,

His habit fit for

speed succinct, and held

Before his decent steps a silver wand.

He

drew not nigh unheard; the Angel bright,

Ere he drew nigh, his radiant

visage turned…

(Milton, III: 636-646)

It’s essentially the same motif of pride and vanity as in Narcissus.

In a similar manner as Princess Cottongrass, he is deprived of his princely and

divine attributes, and incarnates as the Serpent. The divine being takes on

conscious form, and brings a whole horde of angels with him. In the

Book of

Enoch (2nd and 1st centuries BC) the fall of the angels brings immense

knowledge to mankind. Men become conscious of many secrets, and many new

craftmanships. It seems to portray a stage in history when a crisis

occurred due to a massive incursion of unconscious content, followed by a rapid

increase in man’s conscious powers. According to Enoch, men became giants,

then. The giants, with their great capacities, fell to the lure of power and

committed many iniquities.

When this process occurs at the modest level of Cottongrass, it is

much better. But we don’t know why the serpent in the bible wanted men to become

self-conscious. The snake, and the elk, are creatures of instinct. Apparently,

our instinctual nature is favourable to the journey toward consciousness,

although we then lose much of our dependency on instinct. I contend that this

approximates the real meaning of Cottongrass. The great mysteries of the

biblical Fall of Man, and the Fall of Lucifer, are the more grand versions. They

are metaphysical and religious, since gods and angels are involved. By comparison,

Narcissus and Cottongrass are more psychological, as they speak of the same

phenomenon as occurring on a more humble human level. What earlier occurred on the

collective level, as in the

Book of Enoch, may now occur on the individual

level. So one could see these stories as paradigmatic of depth psychology. It’s no

wonder why psychoanalysts love them so dearly.

Interestingly, in Milton’s version, Eve becomes fixated on her own

reflection in the water. Although she is saved by

the voice, this event forecasts her fall from grace:

As I bent down to look, just opposite,

A shape within the

watery gleam appeared,

Bending to look on me. I started back,

It

started back; but pleased I soon returned,

Pleased it returned as soon

with answering looks

Of sympathy and love; there I had fixed

Mine

eyes till now, and pined with vain desire,

Had not a voice thus warned

me: “What thou seest,

What thou seest, fair creature, is thyself…”

(Milton,

IV: 460-468)

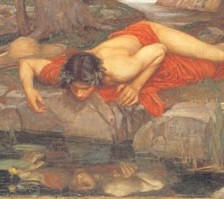

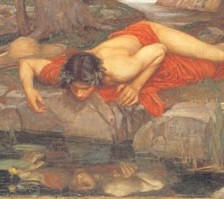

Narcissus and Echo

Narcissus, an exceptionally beautiful boy, was the son of the blue

Nymph Liriope of Thespia. Concerned about the welfare of such a beautiful child,

Liriope consulted the prophet Tiresias regarding her son’s future. Tiresias told

the nymph that Narcissus would live to a ripe old age, “if he didn’t come

to know himself.”

Every youth and girl in the town was in love with him, but he haughtily spurned

them all. One day when Narcissus was out hunting stags, Echo stealthily followed

the handsome youth through the woods, longing to address him but unable to speak

first. When Narcissus finally heard footsteps and shouted “Who’s there?”,

Echo answered “Who’s there?” And so it went, until finally Echo showed

herself and rushed to embrace the lovely youth. He pulled away from the nymph

and vainly told her to leave him alone. Narcissus left Echo heartbroken and she

spent the rest of her life in lonely glens, pining away for the love she never

knew, until only her voice remained.

Nemesis heard this prayer and sent Narcissus his punishment. He came

across a deep pool in a forest, from which he took a drink. As he did, he saw

his reflection for the first time in his life and fell in love with the

beautiful boy he was looking at. Eventually, after pining away for a while, his

life force drained out of him and the narcissus flower grew where he died. It is

said that Narcissus still keeps gazing on his image in the waters of the river

Styx. (Ovid)

(Detail from painting by

J. W. Waterhouse: Echo and Narcissus.)

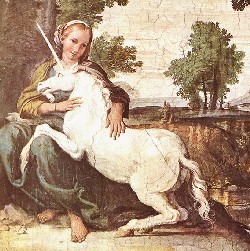

The unicorn

There is an ancient myth, popular as early as the Babylonian era, about the single combat

between the unicorn and the lion. According to a legend of ancient Babylon,

the sun is a lion who constantly pursues the unicorn moon about the sky. The

lion finally manages to win the combat by positioning himself before a tree.

When the unicorn comes dashing the lion suddenly jumps aside, and the unicorn

pierces the tree with its

horn — and is stuck! (cf. Shepard, 2009). The reason why the

battle theme was so popular in the Old Orient is, I believe, because this was a

time when man emerged from a naive and obscure

moon-consciousness into a bright

sun-consciousness.

The battle of the lion and the unicorn was a notorious motif in Sumerian,

Assyrian, and Babylonian times. There is also a unicorn battle in one of

Grimm’s Fairy Tales, presented below.

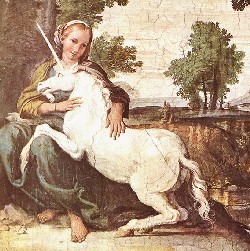

(Detail from painting by Domenichino: Virgin and Unicorn.)

The Valiant Little Tailor (excerpt)

…He took a rope and an axe with him, went forth into the forest,

and again bade those who were sent with him to wait outside. He had not long to

seek. The unicorn soon came towards him, and rushed directly on the tailor, as

if it would gore him with its horn without more ado. ‘Softly, softly; it can’t

be done as quickly as that,’ said he, and stood still and waited until the

animal was quite close, and then sprang nimbly behind the tree. The unicorn ran

against the tree with all its strength, and stuck its horn so fast in the trunk

that it had not the strength enough to draw it out again, and thus it was

caught. ‘Now, I have got the bird,’ said the tailor, and came out from behind

the tree and put the rope round its neck, and then with his axe he hewed the

horn out of the tree, and when all was ready he led the beast away and took it

to the king… (excerpt from story in

Grimm’s Fairy Tales)

The analogy here is the motif of

infixion: the dream creature

is fixed to the tree, whereas the Princess Cottongrass and Narcissus are

fixated on the image in the water. When an archetype becomes fixed, it loses

its divine autonomy and plunges into reality. To an archetypal creature like

the unicorn, this amounts to a degradation. The process of realization is

experienced as expiration and death. In many a myth, this is how death

appeared in the world. Also in the biblical story, death made its entrance at

the fall of Adam and Eve. They were at that very moment degraded from their angelic nature, with divine and

permanent life, to becoming human beings with a temporal and perishable existence.

According to myth, an archetype can accept

its own death willingly, as an act of redemption. The foremost example is the

Christ. By the incursion into material reality the divine being, existent before

the world, gives himself up to death, and takes shape as a mere mortal, namely

Jesus of Nazareth. The power that drives him is love; a motif that

reappears in Princess Cottongrass, whose heart was brimming with love — a good that she wanted to share.

According to tradition, Jesus had the form of a unicorn before the conception.

This is the reason why the unicorn, symbolic of the unconscious archetype

before its arrival in the world, is often seen resting in the Virgin’s lap

(above). This theme is referred to as the “virgin-capture”, when a virgin is used as a

decoy for the unicorn (cf. Shepard, 2009, ch. VIII). The unicorn is viewed as a

prefiguration of Christ, since both became fixed to a tree. Notable is that

Christ was also transfixed by Longinus’s lance.

The fall of Adam is

viewed as catastrophic, since it meant the destruction of a pristine and

unspoilt condition, equal to unconscious wholeness. The analogous process,

which is the voluntary fall of Christ (the second Adam), is a redemptive act.

Mankind, in his fallen state, can only be redeemed by the conscious

realization of an

Idea, equal to the demise of an archetype. It is the reason why the

Christ’s death symbolizes redemption. What was originally regarded a great sin

to a human being, namely to become conscious, is now become a virtue in the

sinful condition. What was before regarded a rebellion against God, in the fall

of Lucifer, is now a redemptive act in Christ’s incarnation. The appearance of

Jesus marks a turning point in history, when unconscious subordination under

religious authority is no longer viewed as an ideal. As usual, the redeeming act comes with a new conscious realization. It implies that Jesus takes the process in the other direction, because he returns to the Father from whence he came. The Incarnation introduced a new narrative around

apotheosis (elevation to divine status).

Coyote

BlueThe motif of the demise of the god is quite old. Coyote is a

cultural hero among North-American Indians. He was responsible for the theft of

fire, which he, thanks to deceit, managed to deliver to the humans (cf.

Compton, 1971, ‘The Coyote’). Coyote lost his beautiful blue colour when he

collided head-on with a tree stump, fell down and became soiled by dirt.

How the Bluebird Got its Color (Pima, Arizona)

A long time

ago, the bluebird was a very ugly color. But Bluebird knew of a lake where no

river flowed in or out, and he bathed in this four times every morning for four

mornings. Every morning he sang a magic song:

“There’s a blue water. It lies there. I went in. I am all blue.”

On the fourth morning Bluebird shed all his feathers and came out of

the lake just in his skin. But the next morning when he came out of the lake he

was covered with blue feathers.

Now all this while Coyote had been watching Bluebird. He wanted to

jump in and get him to eat, but he was afraid of the water. But on that last

morning Coyote said,

“How is it you have lost all your ugly color, and now you are

blue and gay and beautiful? You are more beautiful than anything that flies in

the air. I want to be blue, too.” Now Coyote at that time was a bright

green.

“I only went in four times on four mornings,” said

Bluebird. He taught Coyote the magic song, and he went in four times, and the

fifth time he came out as blue as the little bird.

Then Coyote was very, very proud because he was a blue coyote. He was

so proud that as he walked along he looked around on every side to see if

anybody was looking at him now that he was a blue coyote and so beautiful. He

looked to see if his shadow was blue, too. But Coyote was so busy watching to

see if others were noticing him that he did not watch the trail. By and by he

ran into a stump so hard that it threw him down in the dirt and he was covered

with dust all over. You may know this is true because even to-day coyotes are

the color of dirt. (Judson, 1912)

The motif of beauty and pride is central also here. It is what causes

his downfall. The archetype has reached a high excitation level and is running

at high speed. He commits the same mistake as the unicorn, running headlong into

a trunk or stump. Thus, he comes to an immediate halt and falls down into the

dust. This is symbolic of the process of incarnation, or in psychological terms,

realization. The god has been covered with earth and become a humble little

prairie wolf. Note that Coyote losing his beautiful blue coat is analogous with

the theme in Princess Cottongrass, where she is bereaved of her royal garments.

In this process, the divinity becomes reduced.

OedipusWhat

about the Oedipus tale, then? Oedipus is not formally associated with the dying

gods, but there are significant similarities. He is a hero that suffers demise.

The

Oedipus myth

Oedipus, in Greek mythology, king of Thebes, the son of Laius and Jocasta, king and queen of

Thebes. Laius was warned by an oracle that he would be killed by his own son.

Determined to avert his fate, he bound together the feet of his newborn child

and left him to die on a lonely mountain. The infant was rescued by a shepherd,

however, and given to Polybus, king of Corinth, who named the child Oedipus (“Swollen-foot”)

and raised him as his own son. The boy did not know that he was adopted, and

when an oracle proclaimed that he would kill his father, he left Corinth. In the

course of his wanderings he met and killed Laius, believing that the king and

his followers were a band of robbers, and thus unwittingly fulfilled the

prophecy.

Lonely and homeless, Oedipus arrived at Thebes, which was

beset by a dreadful monster called the Sphinx. The frightful creature frequented

the roads to the city, killing and devouring all travelers who could not answer

the riddle that she put to them. When Oedipus successfully solved her riddle,

the Sphinx killed herself. Believing that King Laius had been slain by unknown

robbers, and grateful to Oedipus for ridding them of the Sphinx, the Thebans

rewarded Oedipus by making him their king and giving him Queen Jocasta as his

wife. For many years the couple lived in happiness, not knowing that they were

really mother and son.

Then a terrible plague descended on the land,

and the oracle proclaimed that Laius’s murderer must be punished. Oedipus soon

discovered that he had unknowingly killed his father. In grief and despair at

her incestuous life, Jocasta killed herself, and when Oedipus realized that she

was dead and that their children were accursed, he put out his eyes and resigned

the throne. He lived in Thebes for several years, but was finally banished.

Accompanied by his daughter Antigone, he wandered for many years. He finally

arrived at Colonus, a shrine near Athens sacred to the powerful goddesses called

the Eumenides. At this shrine for supplicants Oedipus died, after the god Apollo

had promised him that the place of his death would remain sacred and would bring

great benefit to the city of Athens, which had given shelter to the wanderer.

(

Funk & Wagnall’s Encyclopedia)

Oedipus follows the notorious fairytale pattern of the disowned

child, probably representing the Self

archetype, [1], who

later obtains the kingdom. But, in becoming king and guiding principle of

(collective) consciousness, the archetype loses its autonomy and is deprived of

its inner light, i.e., its eyesight. Oedipus, who in his youth was thoroughly

emancipated from mother dependency, again finds himself caught in the embrace of

the mother. What does this mean? The conscious establishment of the archetypal

spirit of Oedipus also means, paradoxically, that the archetype falls prey to

the mother from whom it was initially disengaged. Analogously, Princess

Cottongrass, full of heroism and ambition, left her mother in the Dream Castle,

but ends up stripped of her regalia and bound to Mother Earth.

The immediate breaking free from the mother-tree is a typical theme.

It represents the emancipation of the archetype. Before it was

charged with energy, the archetype was part of a matrix called the collective

unconscious, whose symbolical value is motherly. The energetic aspect is always

underscored. Princess Cottongrass is full of energy. That is why she is

jettisoned from the Dream Castle like a meteor.

The hero toddler is amazingly resourceful. Shortly after Hercules’

birth, Hera sent two great serpents to destroy him. Hercules, although still a

baby, strangled the snakes. On the day of his birth Hermes stole the cattle of

his brother, the sun god Apollo, obscuring their trail by making the herd walk

backward. These hero infants tend to be independent of mother and they

undauntedly confront the dangers of the world.

Oedipus is somewhat similar, although he is more human. He manages to

survive death as an infant. I hold that, first and foremost, we must think of

Oedipus as an archetype that emerges from the deeper layers of the unconscious,

and becomes a free agent, but then again ends up fettered to the earth in the marriage to

his mother. Obviously, then, the Oedipus myth lacks a strong connection

with the Oedipus complex, and we cannot draw the conclusion that boys

have an urge to actually kill their fathers. However, the myth is ideal to use

metaphorically, as an illustration of the complex.

The Oedipal spirit could be exemplified by a new paradigm of

collective consciousness, being resisted by father Laius, representing the old

paradigm. The king represents that old idea of the Self,

the regulating centre of the psyche, that is become representative of the

collective attitude. In rising to glory, the once expansive and powerful spirit,

which is the archetype, is being reduced to

mater-iality. It loses its

autonomy of spirit, becomes carnal and earthly-minded. The archetype,

represented by Oedipus, puts out his own eyes. Thus, the spirit is in the

process of losing its own inner light. Oedipus grew out of the collective

unconscious, and was initially merely a twig on the mother-tree. The archetype

again became dependent on the mother when it fell into conscious material

reality. It is the other side of the mother-principle. He went from one extreme to

the other.

Freudian psychology exemplifies this finely. It emerged as a lively

and charismatic spirit, harbouring an ambition of world dominion. But it became

wholly integrated with material consciousness and consequently reduced to carnality. In

this, it fell prey to the Mother and became mother-bound again. The once proud

spirit can today only contribute with mechanical interpretations that reduce

everything to carnality by means of

genitalization, whereby everything is

understood as a sexual organ. Freudian psychology lost connection with its own

inner spirit, the archetype from whence it emerged. Thus, it has

thoroughly regressed to mother-dependency, which is equal to being caught up in

materiality and an unconscious lifestyle.

So in Oedipus we again find the pattern of the archetype that rises to

eminence after having attained autonomy (independency of the mother) and great

energetic excitation. But in its vainglory, the new idea that broke into the

conscious field also strove after world dominion, without having recourse to other

fatherly principles. The overextension, that is, the attempt to apply it on

everything, is a megalomaniacal effect of archetypal possession. An

unrestricted identification with material reality causes the downfall of the

archetype, and it becomes wholly enmeshed in materiality. Classical Freudian psychology is

today a sad sight, reminiscent of the blind vagabond Oedipus, who finally came

to rest at Colonus. The old king is wandering about the country, with a small

following of caretakers, mumbling about penises and vaginae.

The gender of archetypes and deities

Another factor to consider, relating to the realization of the

archetype, is the gender of the god undergoing

institutionalization. [2] The

conventionalization of gods, in religious

history, seems also to imply masculinization. But is it really justifiable to

take an essentialistic stance as regards the gender of archetypes, as

underlying the concept of divinities? How masculine is the Trinity, really? The

Holy Spirit has time and again come under suspicion of being feminine. His

hidden identity, it has been argued, is Sophia, the spouse of Jahve. Jesus is

often portrayed with feminine attributes; beautiful countenance, long hair,

dressed in a long gown. He gives himself feminine attributes: “[How]

often would I have gathered thy children together, even as a hen gathereth her

chickens under her wings, and ye would not!” (Mat 23:37).

But why is the Trinity experienced as masculine? I hold that it works

like this. A divinity that is pulled out into stark daylight, placed on a

pedestal in a temple, and whose cult becomes institutionalized in dogma and

ritual, will more and more come to be regarded as masculine. The very process of

formalization implies masculinization. Compare with Diana, the Italian forest

goddess. She is a truly feminine goddess because she won’t allow herself to be

pinned down. She exists in the moonlight shadows, where nothing is precisely

defined. She is felt in the whisper of the trees. If somebody

catches sight of her in her naked beauty, then that person must die, because

she cannot allow herself to be pinned down by the eye of consciousness (cf.

Bulfinch, 1998, ‘Diana and Actaeon’).

What would happen if Diana was

caught, put on a pedestal, and intellectually defined in theology and dogma? It

would go like it always goes with deities. She would acquire more and more

masculine attributes, much like Athena, who was furnished with a suit of armour

and became a war goddess. Due to the fact that she has been pulled into

the daylight from her lush woodlands, and become institutionalized, she would

come to be regarded as masculine. Such a daylight condition is not experienced

as feminine. Soon the divine being will have been transformed to intellectual

words in a book, and she has then become wholly theologized.

So what would have happened to a feminine Trinity? It would have become masculinized in dogma. Only if it

remains in the shadows of the wood can it abide as a feminine

deity. The conclusion is that there is no other choice than to have a

masculine godhead in a culture where consciousness has reached a pronounced level of

penetrative capacity. Only in ancient cultures where people lived with half-closed

eyes, as it were, may a feminine divinity roam about. At such a cultural

level they would never theologize her, and would refrain from looking directly at her.

In fairytales and in alchemy, the old conception of the Self, associated with daylight collective

consciousness, is viewed as masculine. He is the

old king. Thus, the concept

of the Self, when it is being defined in consciousness by

exemplification in books, will become asymmetrically masculine and logos-oriented.

ConclusionInfixion of the god or goddess signifies either incarnation or realization. From a mytho-religious perspective, it signifies the incarnation of the divine

principle in the world, and in the soul of man. What is portrayed in these myths

is a mystery, underlying the greatest passion known to mankind; the

spiritual passion. Notice the many interesting parallels between the

myths. Cottongrass and Jesus are both stripped of their clothes before being infixed (also Coyote Blue loses his clothes, in a sense). Both are of

royal/divine ancestry and were driven by love. The self-sacrificial act on part

of the archetype implies that a great boon is conferred on humankind and the

temporal domain. From the perspective of individual psychology, the process of

unconscious integration emancipates the individual from dependency on the

unconscious, and approximates the personality better to the Self.

Wholeness is a state in which consciousness and the unconscious work

together in harmony. It has a wholesome effect on the life and health of

the individual. Analogously, the process of incarnation serves the purpose of regaining

the wholeness which was lost at the Fall of Man.

© Mats Winther (Nov 2009)

Definitions

Self : the archetype of wholeness and the regulating center

of the psyche; a transpersonal power that transcends the ego. “It expresses

the unity of the personality as a whole […] The self is not only the centre,

but also the whole circumference which embraces both conscious and unconscious;

it is the centre of this totality, just as the ego is the centre of

consciousness.” (Jung,

loc. cit.) […] Like any archetype, the

essential nature of the self is unknowable, but its manifestations are the

content of myth and legend. “The self appears in dreams, myths, and

fairytales in the figure of the ‘supraordinate personality,’ such as a

king, hero, prophet, saviour, etc., or in the form of a totality symbol, such as

the circle, square, ‘quadratura circuli’, cross, etc.” (Jung,

loc. cit.)

(Sharp, 1991).

Institutionalization : to

incorporate into a structured and often highly formalized system. (

Webster’s

Dictionary)

ReferencesBulfinch, T.

(1998). Bulfinch’s Mythology. The Modern Library.

Compton, M. (1971). American Indian Fairy Tales. Dodd, Mead & Company. [1907] (

here)

Franz, M-L von (1996). The Interpretation of Fairy Tales. Shambala.

Judson, K. B. (ed.) (1912). Myths and Legends of California and the Old Southwest.

Olenius, E. (ed.) (1974). Great Swedish Fairy Tales. Delacorte Pr / Seymour Lawrence.

Ovid (1st century). Metamorphoses. Wikipedia summary.

Schwartz-Salant, N. (1982). Narcissism and Character Transformation. Toronto: Inner City

Books.

Sharp, D. (1991). Jung Lexicon: A Primer of Terms & Concepts. Inner City Books. (

here)

Shepard, O. (2009). Lore of the Unicorn. Evinity Publishing Inc. [1930] (

here)

Solms, M. (2004). ‘Freud Returns’. Scientific American, May 2004. (See also Counterpoint

by J. A. Hobson.) (

here).

Taylor, E. &

Edwardes, M. (transl.) Grimm’s Fairytales.

The next day, with the princess on his back, he races into the forest. Fortunately, he manages to restrain himself and slow down. Again he cautions her not to let

go of his horns, this time when a witch questions her. But as her dress begins

to slip away, she reaches for it and the witch grabs it. He tells her how lucky

she is; if she had let go with both hands she would have had to go with the

witch.

The next day, with the princess on his back, he races into the forest. Fortunately, he manages to restrain himself and slow down. Again he cautions her not to let

go of his horns, this time when a witch questions her. But as her dress begins

to slip away, she reaches for it and the witch grabs it. He tells her how lucky

she is; if she had let go with both hands she would have had to go with the

witch.

Every youth and girl in the town was in love with him, but he haughtily spurned

them all. One day when Narcissus was out hunting stags, Echo stealthily followed

the handsome youth through the woods, longing to address him but unable to speak

first. When Narcissus finally heard footsteps and shouted “Who’s there?”,

Echo answered “Who’s there?” And so it went, until finally Echo showed

herself and rushed to embrace the lovely youth. He pulled away from the nymph

and vainly told her to leave him alone. Narcissus left Echo heartbroken and she

spent the rest of her life in lonely glens, pining away for the love she never

knew, until only her voice remained.

Every youth and girl in the town was in love with him, but he haughtily spurned

them all. One day when Narcissus was out hunting stags, Echo stealthily followed

the handsome youth through the woods, longing to address him but unable to speak

first. When Narcissus finally heard footsteps and shouted “Who’s there?”,

Echo answered “Who’s there?” And so it went, until finally Echo showed

herself and rushed to embrace the lovely youth. He pulled away from the nymph

and vainly told her to leave him alone. Narcissus left Echo heartbroken and she

spent the rest of her life in lonely glens, pining away for the love she never

knew, until only her voice remained.

There is an ancient myth, popular as early as the Babylonian era, about the single combat

between the unicorn and the lion. According to a legend of ancient Babylon,

the sun is a lion who constantly pursues the unicorn moon about the sky. The

lion finally manages to win the combat by positioning himself before a tree.

When the unicorn comes dashing the lion suddenly jumps aside, and the unicorn

pierces the tree with its

horn — and is stuck! (cf. Shepard, 2009). The reason why the

battle theme was so popular in the Old Orient is, I believe, because this was a

time when man emerged from a naive and obscure moon-consciousness into a bright sun-consciousness.

The battle of the lion and the unicorn was a notorious motif in Sumerian,

Assyrian, and Babylonian times. There is also a unicorn battle in one of

Grimm’s Fairy Tales, presented below. (Detail from painting by Domenichino: Virgin and Unicorn.)

There is an ancient myth, popular as early as the Babylonian era, about the single combat

between the unicorn and the lion. According to a legend of ancient Babylon,

the sun is a lion who constantly pursues the unicorn moon about the sky. The

lion finally manages to win the combat by positioning himself before a tree.

When the unicorn comes dashing the lion suddenly jumps aside, and the unicorn

pierces the tree with its

horn — and is stuck! (cf. Shepard, 2009). The reason why the

battle theme was so popular in the Old Orient is, I believe, because this was a

time when man emerged from a naive and obscure moon-consciousness into a bright sun-consciousness.

The battle of the lion and the unicorn was a notorious motif in Sumerian,

Assyrian, and Babylonian times. There is also a unicorn battle in one of

Grimm’s Fairy Tales, presented below. (Detail from painting by Domenichino: Virgin and Unicorn.)

Oedipus, in Greek mythology, king of Thebes, the son of Laius and Jocasta, king and queen of

Thebes. Laius was warned by an oracle that he would be killed by his own son.

Determined to avert his fate, he bound together the feet of his newborn child

and left him to die on a lonely mountain. The infant was rescued by a shepherd,

however, and given to Polybus, king of Corinth, who named the child Oedipus (“Swollen-foot”)

and raised him as his own son. The boy did not know that he was adopted, and

when an oracle proclaimed that he would kill his father, he left Corinth. In the

course of his wanderings he met and killed Laius, believing that the king and

his followers were a band of robbers, and thus unwittingly fulfilled the

prophecy.

Oedipus, in Greek mythology, king of Thebes, the son of Laius and Jocasta, king and queen of

Thebes. Laius was warned by an oracle that he would be killed by his own son.

Determined to avert his fate, he bound together the feet of his newborn child

and left him to die on a lonely mountain. The infant was rescued by a shepherd,

however, and given to Polybus, king of Corinth, who named the child Oedipus (“Swollen-foot”)

and raised him as his own son. The boy did not know that he was adopted, and

when an oracle proclaimed that he would kill his father, he left Corinth. In the

course of his wanderings he met and killed Laius, believing that the king and

his followers were a band of robbers, and thus unwittingly fulfilled the

prophecy.