Abstract: There are two forms of creativity, our daytime

creativity and its unconscious complement (my conjecture). An unconscious

semi-autonomous spiritual power ever searches to manifest itself in human life.

In dreams it is often symbolized by the phallus, in alchemy by the spirit

Mercurius. It is hampered by modern-day rationalism and the reductive view of

the unconscious as mere drive nature and repressed content. What is even more

damaging to the unconscious creative force is the romanticizing tendency present

among Jungians and followers of New Age. The technique of ‘active imagination’,

due to a romantic obsession with symbolic imagery, is likely to block out a true

creativity. Hence conscious attachments cannot be abandoned. It makes impossible

the goal of the immersion in the unconscious, so central to mystical and

spiritual discipline. The corrupting influence befalls the very people who are

favourably disposed toward the unconscious, and their creative instinct is

wounded.

Keywords: creativity (“solar” and “lunar”),

painting, psychoanalysis, phallus, romanticism, mysticism, alchemy, Picasso,

critique of active imagination.

Introduction

A spiritual form of creativity seems to be a constant concern in the dreams

of modern people. In my dreams I discover that my clothes have been stained with

oil paint. It makes me irritated. Who is slopping oil paint on my clothes all

the time? Those dreams only stop when I start painting in oil. A good example

are the spiritual paintings of Australian aborigines (Wiki, here),

an activity that has gone on for 40,000 years. A case in point is the common

phallic symbol that typically points at spiritual content in dreams.

Psychoanalysts have caused great damage by again and again misinterpreting this

symbol in the traditional sexual way. Two examples of phallus dreams, which the

unconscious tirelessly produce in modern people:

A British male dreams: “I am studying ancient musical instruments, and have an ancient Egyptian trumpet. I take it off the wall. Somehow, a former work colleague is involved as an expert. I try to blow the trumpet, but have problems. I cannot blow hard enough to make a proper sound…”

An American male dreams: “I had a dream about a penlight that began to make a high pitched sound, which started off soft, but became louder and louder until the sound it made threatened to destroy the entire world…”

The trumpet is an eminent phallus symbol, as is the pen. It is a symbol of

spiritual power in some form. Sound is very “spiritual” in a sense, as

it is invisible. The spirit wants to manifest, but it needs help to do so.

However, the dreamers cannot yet handle the trumpet or pen. Likely, it is

something in themselves, some capacity which they underestimate, which holds the

key to sounding the trumpet and writing with the spiritual pen. A penlight is a

perfect phallus symbol — ‘phallus’ means the “shining one”. Light

is very “spiritual” in a sense. One can write about spiritual matters

with this pen. Obviously, it wants to make itself heard, and if nobody picks it

up it will scream louder and louder until the whole world is threatened.

Such dreams use the phallus to point at the spiritual creative factor, and to

highlight its immense importance. Creation by sound occurs in myth. According to

an Egyptian creation myth, the universe was created at the cry of the goose: the

sun was said to be an egg laid daily by Geb, the “Great Cackler”. He

took the form of a goose, whose piercing call awakened all the movement of

creation. Just imagine how the two dreamers would have been misled by their

psychoanalyst, had they attended therapy. Analysts steeped in the tradition of

infantile sexuality would have destroyed the healing attempt of the unconscious.

Psychoanalysis won’t make significant headway until it integrates into its

theory the notion of the creative spiritual factor, symbolized by the phallus.

The greater part of the unconscious is being neglected, but it demands

recognition. The unconscious is in psychoanalysis defined as the repository of

our drive nature. To this is added the ramifications of our relations with our

parents, etc. However, the unconscious contains another part. This is the “spirit”.

So spirit is that part of the unconscious which is not rooted in the

mundane. This unconscious force must be articulated. Psychoanalysis must

integrate the notion of the spiritual unconscious. Otherwise patients will

suffer because their unconscious urges continue to be neglected. The dream symbols

are likely to be misinterpreted, which makes matters worse.

The romantic entrapment

There is yet another factor that can damage an

healthy creativity. It is the romanticizing tendency represented by the

Jungian psychoanalytic school and the New Age movement. Carl Jung

said that he found the images of his patients much more interesting than those

of modern artists. He didn’t much like modern art. I do concede that there exist

much nonsense in the art world, but I do not agree with Jung’s evaluation.

Although the symbolic properties of images are quite relevant I am more

attracted to images on account of their organic nature. Modern art tends to

look into the spirit of matter itself, whereas the images of Jung and his patients

revolve around “ideas”. I am surprised at the great success of the Red Book

(Wiki, here).

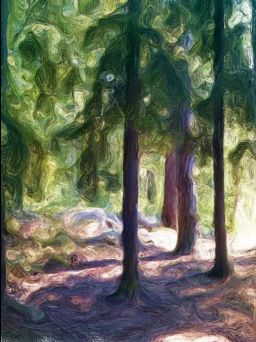

Personally, I am not at all enthralled by Jung’s images. On the other hand, I

find oil paintings at a high degree of abstraction very attractive, like this

one with forest themes, by H.R. Berntson:

(“The

forest”. Reproduced with permission from

Galleri Överkikaren)

Such images really awaken something in me. This I suspect is the

spiritus mercurialis, which is the creative spirit of the unconscious.

In my daytime creativity I am good at programming computers and writing

intellectual articles, etc. But the unconscious form of creativity is something

quite different. It is hard to get at when one’s daytime creativity is of quite

another nature. It is as if all the means are at one’s disposal, but one lacks

the power to blow the artistic trumpet. What is lacking is the creative

instinct, it seems. To me, the organic nature of oil/acrylic painting, at a

reasonably abstract level, represents the inroad to the spiritual form of

creativity that springs from the unconscious. I have tried making “Jungian”

symbolic images, but they fail to engage me. Probably it has to do with their

ideational nature. They are too close to my conscious standpoint, which always

revolves around ideas.

This

unfinished image represents an attempt of me to paint according to the symbolic

and romantic ideal. I have tried many times, but lose interest before the

painting is finished. There is a conscious attraction to such images as I can

relate to their symbolic meaning, but my unconscious finds the romantic attitude

appalling. So it’s like I am refused further energy to finish off the painting.

This

unfinished image represents an attempt of me to paint according to the symbolic

and romantic ideal. I have tried many times, but lose interest before the

painting is finished. There is a conscious attraction to such images as I can

relate to their symbolic meaning, but my unconscious finds the romantic attitude

appalling. So it’s like I am refused further energy to finish off the painting.

(unfinished “romantic”

painting) This crude nature

study is better. It is more “instinctive”.

This crude nature

study is better. It is more “instinctive”.

(oil pastel by me)

Sacrificio Intellectualis

Arguably, in order to find the true spiritual form

of creativity, one must make a “sacrificio intellectualis”,

and give up one’s daytime creativity. What I am searching for is a form of

creativity — no matter how unostentatious — that is capable of stirring

the creative instinct. (Perhaps Jung’s sandplay experiments were of this order.)

It coincides with that dive into the unconscious waters, away from conscious

involvements, which is termed the nigredo in alchemical terminology.

This does not lead to the dissolution of the ego, on Jungian lines. I

contend that it refers to the simple and unconscious life, in tune with creative

instinct. This is what the medieval alchemists experienced when they

experimented with their chemicals. The unconscious creative spirit, very

essential to the psychological process, came to expression (or tried to come to

expression) in the chemical work itself. Arguably, to find this form of

creativity is essential as it works as a carrier wave during the “dark

night of the soul”, the introvertive period in the spiritual journey of the

modern mystic. The creative activity has been underestimated in mystical

theology. Also, the way in which medieval alchemy tends to be interpreted,

solely on symbolical lines, underestimates the creativity rooted in instinct.

There is a lot of ideational content in alchemy, but one shouldn’t think that

this is the essential truth about alchemy, i.e., what alchemy is all about. This

would be equal to throwing the baby out with the bathwater. I don’t deny that

what underlies alchemy is the

psychological process. However, it doesn’t seem like psychological

images and archetypal ideas can stir up the said spiritual form of creativity,

at least not in many of us modern people.

Hence, I believe that the

rather “romantic” Jungian view of creativity could have damaging

consequences — in many cases it could thwart a true spiritual form of

creativity. So, to my view, the above oil painting by Berntson is truly

alchemical, whereas Jung’s own paintings represent more of a romantic spiritual

attitude, on Gnostic or theosophical lines. This might be the correct path for

some people, but for many of us it represents a blind alley.  I have been experimenting

with photographs, which I elaborate in PaintShop

Pro

(Wiki, here) and Painter

Essentials

(Wiki, here). I took this photo the other day, which was converted to an “oil

painting” in Painter Essentials. It has some of that organic character

which I find attractive. However, a strange thing occurred. The program created

curious anomalies in the picture that look very much like eyes. They are looking

straight out of the trees, the roots, etc., although they are not all visible in

this diminished image. When I took the image, it seems as if the spirit of

nature, Mercurius, was looking back at me, although I wasn’t aware of it. As we

gaze into the unconscious, there is an archaic form of consciousness looking

back at us — the spirit imprisoned in matter. “Nature” in this case

represents the ‘materia prima’ of the alchemists. This “inferior”

substance is the stone that the builders rejected.

I have been experimenting

with photographs, which I elaborate in PaintShop

Pro

(Wiki, here) and Painter

Essentials

(Wiki, here). I took this photo the other day, which was converted to an “oil

painting” in Painter Essentials. It has some of that organic character

which I find attractive. However, a strange thing occurred. The program created

curious anomalies in the picture that look very much like eyes. They are looking

straight out of the trees, the roots, etc., although they are not all visible in

this diminished image. When I took the image, it seems as if the spirit of

nature, Mercurius, was looking back at me, although I wasn’t aware of it. As we

gaze into the unconscious, there is an archaic form of consciousness looking

back at us — the spirit imprisoned in matter. “Nature” in this case

represents the ‘materia prima’ of the alchemists. This “inferior”

substance is the stone that the builders rejected.

‘Materia

prima’ is primitive nature. In a dream I am urged to “follow the Negro”:

“I start following him as he successively becomes more like an animal. He

starts running on four legs, like a hound. He runs into the bush. I take after

him.” (In dreams of Westerners, black people typically play the

unflattering role of primitive humans). What does this mean? It means that I

ought to become “inferior, instinctual, and unconscious”, as an

advanced consciousness presents a hindrance to finding the ‘materia prima’.

In this process, creativity plays an important role. I argue that the instinctual

and “inferior” creative power abides in the unconscious. Jung devoted

his life to writing intellectual books. But his anima (in the shape of Sabina Spielrein, it seems) urged him to abandon his “superior”

function and instead devote himself to inferior “art” and sandplay. It

is probably the same motif as in my own dreams, where I am urged to abandon my

superior function. Jung, however, rejected the anima’s suggestion out of hand,

as an attempt to take control over consciousness. This is a very controversial

interpretation, as if the anima was being solely destructive. The result was

that he over-extended his conscious function. In the collected works he often

repeats himself. Arguably, he deviated into romantic creativity, as he had

rejected the unconscious creative source, rooted in instinct: the “creativity

of the Negro”, as it were.

Picasso was inspired

by black African art, as in this example. Art rooted in the black soil

represents the ‘materia prima’, the stone which many in the Jungian school, and

the New Age movement, have rejected.

Picasso was inspired

by black African art, as in this example. Art rooted in the black soil

represents the ‘materia prima’, the stone which many in the Jungian school, and

the New Age movement, have rejected.

(Picasso:

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

Wikipedia, public domain)

The Stone

The Stone of the alchemists, I suggest, is the raw material

for a creativity rooted in the spirit, which we discover in the unconscious. In

our everyday lives we are very much occupied with the mundane, whether its

pleasure, search for wealth, power, etc. So that’s why the unconscious produces

the fantasy of the spiritual Stone, like in my own dream from decades ago when I

dreamed about finding the “uranium stone” in the Holy land. In the

dream I immediately started to work diligently to refine its properties,

together with my companions. The Stone generates a spiritual form of

creativity, because it contains another kind of energy than the mundane.

However, being creative often means to occupy oneself with matter, as in the

work of the artist. Actually, artists have always worked with led which they

have turned into “gold”, in a sense. ‘Led white’ has superior

qualities, but today’s artists seldom use it since it is poisonous. ‘Naples

yellow’ was originally made of led, but it’s seldom used today.

The alchemical gold, or the Stone, as the end product of the opus, is

often interpreted as the reunion of the body with the conjugate of spirit and

soul, the latter having undergone refinement. It is thus a symbol of the self

(cf. “Jung Lexicon”, here).

But such a symbol harbours a multitude of opposites. To interpret it in terms of

a dark and unconscious form of creativity, a spiritual source of energy that can

be exploited, is merely looking at it from another angle. To achieve the ‘unio

mentalis’, a form of spiritual one-sidedness, is probably necessary to get at

this source. I once had the following dream. “…I was about to enter a

chess tournament in a dark palace. But I had some time left so I went to a

nearby city where I visited a beautiful rose-red castle. I was thinking that I

should paint it some day. But now I had to return to the dark and gloomy

palace to take part in the demanding chess tournament.”

The

rose-red castle, and the notion of painting it, represents a romantic day-time

creativity, whereas the rather technical chess tournament signifies a

creativity related to the unconscious. It is similar to attending a mathematics

course, solving integrals and differential equations. The spiritual

(alchemical) work is like gazing into a chequered little world where variations

are discovered. It seems to imply that consciousness should focus on a little

world, symbolized by the alchemical vessel. The symbol of chess is apt. The

chess board represents the vessel, in which the warring elements give birth to

variations under the supervision of a focused consciousness. It is partly the

conscious function that causes the variations to take place, as it adds “heat”

to the vessel. However, there is also an opponent in the game, representing

another kind of consciousness. This is the serpent’s eye gazing back at us from

the unconscious. It is a faint light, but it represents an age-old wisdom.

The spirituality of the Stone (the spirit Mercurius) emerged in the

medieval era. The earlier antique form of spirituality was of another kind. It

died out in late antiquity. Plutarch (d. AD 120) relates (in Cessation of the

Oracles) that the passengers of a ship, while passing by a group of islands on

the coast of Greece, heard a mysterious voice proclaiming that “The great

god Pan is dead”. At this there came the sound of a mighty groaning and

lamentation from countless throats. Emperor Tiberius set up a commission to

investigate the matter. They managed to find witnesses who corroborated the

story (cf. Walker, “Gnosticism”, pp.72-73). A god can never really die, of course,

but the epoch of Pan was over. I myself have dwelled with this spirit in my

life. In one dream a voice told me: “You ought to be like Pan for a time.”

It means to immerse myself in the waters of antique spirituality. But I cannot

stay there because it leads nowhere, although it is good for healing purposes.

Finding the Stone, which contains the spirit Mercurius, is a more advanced form

of spirituality. It signifies, I think, a creativity rooted in the spirit, that

remains in the unconscious. When this source has been found one can be creative

and continue to “search”. Life becomes rooted in the spirit, and the

personality is no longer psychologically dependent on the worldly energies.

As to the phenomenon of “alchemical humbug”, e.g. people

who claim to have possession of the Stone in its material guise. I think this

belongs to the category of ritualization, i.e. the way in which people

tend to create a new religion out of an impressive phenomenon. Today’s

consumerism implies that people go on pilgrimage to shopping centres and

purchase fetish objects. This richness in furnishings gave rise to the “cargo cults” (Wiki,

here)

among primitives who adopted white man’s cult. So the primitives “imitated”

white man’s lifestyle and made a ritual out of it. This ritualizing factor is

born out of man’s religious temperament. Likewise, there is a tendency, on

lines of New Age, to make a religion out of alchemy. Personally, I tend to be

favourably disposed toward religion, in a general sense, because it belongs in

human nature. However, an alchemical religious attitude can rouse annoyance as

it contravenes the very spirit of alchemy, namely as an alternative path to

religion. If people start worshipping the Stone as a material object created in

the laboratory, then it can put the lid on the said spiritual creativity.

Alchemy, I think, is meant to go beyond religion, i.e., not imitating through

ritual, but experiencing it yourself.

I have called this phenomenon “romantization”, the tendency

to romanticize the spiritual path, through ritualization and fantastication.

After the Middle Ages, alchemy became more and more romantic, high-flown,

occupying itself with beautiful imagery, etc. But the Stone is hidden in the

mud. As it appears crude and simple it tends to be neglected, but it can be

refined immensely.

Enlightenment versus unconsciousness

The

‘unio mentalis’ is concerned with separation from ordinary desires and

affliction caused by life. It is a form of spiritual one-sidedness, central to

Christian mysticism and Buddhism. The Gnostics and the psychoanalytic movement

want to achieve ‘enlightenment’, whereas Christian mysticism revolves around

‘the dark night of the soul’, i.e. entering an unconscious state. Spiritual

discipline should be capable of integrating both these aspects. In fact, alchemy

could be understood along these lines. First, enlightenment is achieved, then

the artifex commits himself to unconsciousness. Both states are characterized by

different forms of one-sidedness, I suppose. This dream of a British male

illustrates the process:

“I was outside time and space, about to enter existence. In front of me was a tapestry, which I was studying. A man walked across the tapestry (which came to life), and the sun was visible in the sky. Suddenly the sun became his head, and then I entered the scene and became the man.

Next, I was Picasso, standing on a beach somewhere by the Mediterranean Sea. I had been commissioned to paint Christ walking on the waters, and I felt that in order to do this work properly, I must try to do it myself. I tried to do so, and sank beneath the waves. As I sank down for the third time, apparently drowning, a beautiful silvery-green dolphin appeared. It held me in its mouth and swam back to the shore, leaving me safely on the beach.”

The dreamer first becomes enlightened. The sun is his head, which would mean

identification with the fatherly sun-god. (The man with the sun head is a

recurrent theme in alchemy.) Then he becomes Picasso and steps out on the

water. This probably signifies entering an unconscious state. Picasso was an

unconscious and “primitive” person who made Negro art (he was inspired

by black African art). The ability to walk on water probably symbolizes the

capacity to remain unconscious. It is like being able to breathe under water,

that is, one can sustain life in an unconscious condition. In this state the

artifex has recourse to a primitive creative capacity, such as Picasso’s form of

creativity, which was “nonsensical” in a sense, following the ideal of

unconsciousness. But the other pole wasn’t known to Picasso the artist.

Arguably, it is necessary to know the two poles of light and darkness to be able

to act as mediator. First comes enlightenment, and then comes the other

opposite, descent into unconsciousness, to remain in a self-effacing

condition, which is characteristic of the mystical traditions, I think.

Picasso could be understood as the god of the unconscious, i.e.

Mercurius. As the dreamer identifies with him, he becomes unconscious. The

dreamer carries the role of the mediator between the two gods. That’s why he

enters the water, i.e. he enters the unconscious, as the Christ descended into

the underworld in the time between his crucifixion and resurrection. C.G. Jung says that the sonship of God must be extended to many more

individuals. This is also the underlying goal of Christian mysticism. The

dreamer is brought back to ‘terra firma’ again by the benevolent force of the

unconscious, signifying “resurrection”. (I don’t know what it means

that the dreamer fails to walk on water.) In Picasso’s form of unconscious

creativity, the part pertaining to unconsciousness is fulfilled, but

enlightenment risks being forgotten. Artists, practical alchemists, and New

Agers, are all well-trained in the art of abiding in unconsciousness, but

enlightenment must be achieved in order for the artifex to act as mediator

between heaven and earth.

This is logical, isn’t it? Conscious and unconscious, spirit and

soul, must be united, according to the alchemical formula: coniunctio Solis

et Lunae. But for this to be achieved, consciousness must be conquered.

People are naturally reluctant to becoming conscious, because it is a painful

process, especially the realization of the evil nature of mankind, and the

ongoing destructive processes in the world. It is always easier to remain in a

kindergarten existence, remaining comfortably unconscious. Picasso’s art was “silly

and nonsensical”, as many have argued. Yet it is a potent unconscious

power, and it is therefore a good thing, when it serves the purpose of slaking

the fire of the sun. This is reminiscent of the green lion devouring the sun in

alchemical imagery. However, if there is no sun to devour, but only a faint

shining cloud, then nothing is gained by the spiritual rituals or the painting

activities, except the creation of art. Then it’s merely an hobby, and the

hobbyist generally has no success on the spiritual path.

To sink into

unconsciousness is a very potent action. The artifex himself becomes the seed

that is planted in the earth. To entertain an unconscious state, to be involved

in “nonsensical” activities like making abstract art à la

Picasso, or to dabble with chemicals, is very good, but only if the person is

already laden with conscious power, which is now being injected into the

unconscious. But if the spiritual searcher, or contemplative, hasn’t achieved “enlightenment”,

i.e. become conscious enough, then the descent into nigredo (darkness of

the soul) will not bring fruition. We normally speak of unconsciousness as

destructive and unfavourable — the root of all evil in humankind. But there

is a benevolent side of this quite dangerous phenomenon. That primitive,

unconscious, “Picasso-creativity”, is capable of nourishing a benign

condition of unconsciousness. It is a golden form of unconsciousness, a valuable

unconsciousness.

A benign unconsciousness

When

consciousness has developed to an acute level, it can relieve the pressure and

have an wholesome effect, if one allows oneself to sink down into

unconsciousness. A descent into the unconscious need not entail the dissolution

of the ego. It refers to the simple and unconscious life, to remain in a

self-effacing condition, in tune with creative instinct. [1]

The benign form of unconsciousness (‘the dark night of the soul’ of the mystics;

the ‘nigredo’ of the alchemists) is the “good side” of the dark deity,

as it were. Its realization is of immense import. Consciousness should not rule

supreme, but we must remain in tune with our heart, and with our instincts. For

instance, we mustn’t take upon our shoulders the moral burden of God, assuming

responsibility for all the brown-skinned people in the world. In fact, it is

better to remain unconscious of their sufferings than to do everything to

sustain them, following UN:s “Humanity Maximization Principle”,

which leads to nothing good. People today tend to program themselves with the

abstract values of consciousness and forget to listen to their heart. They think

they are empathic, but they are only slavishly following an ideological

algorithm programmed into their head. It has nothing to do with empathy.

There is another form of consciousness, a “dark” consciousness, which

leads us to withdraw into a smaller world. To care for our cat — that’s

empathic — because it is in tune with instinct. It is a lesson for

psychoanalysis to learn, that not every problem can be solved by realization,

realization, and yet more realization. Sometimes repression provides the

solution, to become comfortably unconscious. The following is the neurotic mantra of our

age: science and yet more science – technology and yet

more technology – welfare and yet more welfare – medicine and yet more medicine – economic expansion and yet more

economic expansion – globalization and yet more globalization – multiculturalism and yet more multiculturalism. The

collective identification with the conscious values has now reached such

proportions that the Western civilization can be said to suffer from neurosis.

This explains the sudden outbreak of psychotic destructivity, as in the recent

Norwegian mass-murder (July 22, 2011, Oslo and Utöya). Norway is at the

pinnacle of Western civilization, its richest and most beautiful country. It is

symptomatic that the devil (as the revolting unconscious) should strike back and

have his revenge at this very place. He made his deadly counterattack at a

social democratic political camp where youths were busy programming themselves

with the above mantra. The victims of this horrible crime were exponents of an

ongoing collective neurosis. The terror deed was symptomatic, a psychotic

episode in the collective psyche, as it were.

The creativity of the child

The gist of my

idea is that unconsciousness has a bearing on creativity in art. Take

for example the child artist prodigy Marla Olmstead, who could

paint masterpieces already at the age of 4. She was capable of this due to her

childish unconscious state. The channel to the creative spirit is still

open at this early age. That’s why so many artists, like Dubuffet, Jörn,

and Miro, have tried to emulate childish creativity.

It works reciprocally. In order to return to a blessed

and positive form of unconsciousness, we can make use of the instinctual force

of artful creativity, but not the romantic form, which is an aberration of

consciousness. One of the most popular images of all times is the Island of

the dead, by Arnold Böcklin. It symbolically depicts the

unconscious romantic position, namely the longing away from the turmoil of life to a stage of incubation in a protected temenos. It represents a healthy compensation of an exaggerated extraverted position.

(The island of the dead, by Arnold Böcklin. Wikipedia)

The unconscious creative force is spirit. That’s why, in olden

times, people like Jackson Pollock and Asger Jörn,

would have been regarded as shamans. This view is apt because, in their

unconscious condition, they connected with the spiritual realm. Skeptics have

argued, in the case of Marla Olmstead, that she could not have

done such driven paintings at this low age. In a sense they are right. It is the

age-old spirit of the unconscious who has inspired the paintings. The artist is

merely the intermediary. That’s why you get the impression that this cannot be

right, some much older master must have a hand in these paintings. Anyway, this

is yet another indication that truly creative art is contingent on a

semi-autonomous spirit of the unconscious, something akin to a daimon.

In the above picture a “god” makes its appearance on the canvas. In

paleolithic times it is believed that children sat on the shoulders of parents

when painting. I suggest that the grownups realized that the children could make

contact with the spirit, as they could create a random pattern and then build

upon it, allowing divine images to take form. We know that paleolithic artists

made use of natural patterns in the rock. See article “Children’s Cave Art

Dates Back 13,000 Years” (here).

It was the surrealists who invented automatism, to paint or write

with as little conscious control as possible. Salvador Dalí

said that what characterizes a good painting is that you want to “eat”

it. A feeling in the stomach decides if it’s good art. An interesting technique

is to wet a canvas with colour, put creased paper on it, and then withdraw the

paper when the paint has dried for a time but is still wet. This will create

random patterns in the paint and fine shades. The painting can be developed from

this, and forms will grow out of the pattern. Today, this technique can be used

with acrylics and plastic foil. It is a good idea to start out from a randomly

generated pattern as it releases the processes of association, i.e. it

functions as an allure to the unconscious. Visually, unconscious archetypes

emerge out of the image as the figures take on a more concrete form derived from

the initial diffuse shapes. Asger Jörn’s paintings are highly

enjoyable. Jörn, who belonged to the COBRA art movement, was fond of

painting mythological motives, especially from Norse mythology. The trolls are

abundant, they emerge out of the painting. The COBRA members took exception to

the way that surrealism had developed. They focused on spontaneity and

experiment. They were inspired by children’s drawings, primitive art, and the

work of Klee and Miró.

Art springs from the unconscious, but

the unconscious does not follow the Platonic principle of “archetypal

necessity”. Rather, the archetypes could be denoted “diffuse shapes”,

because they are “spirit”. The archetypal expression springs from a

cooperative effort of conscious and unconscious. The artist must give substance

to the archetypes himself. So a random pattern generated with acrylic paint and

plastic foil is a perfect ground for painting as it contains “spirit”.

This is an ancient tradition that appears in all high cultures, i.e. the notion

that the spirit manifests in the diffuse patterns, for instance, in coffee

grounds. Random generated patterns have always been used for divinatory

practices because they contain “spirit”.

Active imagination as romantic creativity

Romantic

creativity is a perversion of the creative function. It can develop into a form

of addiction. As long as the individual leads the life of a dreamer, which is a

moderate form of romanticism, then not much harm is done. But ‘active

imagination’ implies that the romantic attitude is intensified. It risks

developing into addiction. I don’t know whether this is the case in all forms of

active imagination, but in many cases it represents a misuse of fantasy, such

as the tendency toward fantastication. The Jungian form of creativity depends on

the notion of ‘active imagination’. It revolves around archetypal symbols, which

accounts for its romantic character.

Is Jung’s active imagination a significant method of integration of

unconscious content, as asserted by Jung? Comparatively, therapy has

demonstrated its healing capacity in many cases, but is there any study which

proves the usefulness of active imagination as psychological method

rather than as spiritual exercise? Jung seemed to think that his own notion of

the journey of individuation, the successive confrontation with “shadow – anima/animus – mana personality – self”, can function as a substitute for

the spiritual traditions, although many people, due to their old-time

psychological constitution, ought to remain within traditional religion.

In Two Essays, and elsewhere, Jung describes the ‘anima’

as the transcendent function (i.e., bridge to the unconscious), and the ‘mana

personality’ that stands behind her (cf. “Jung Lexicon”, here). The question is, have followers of Jung

integrated the anima and encountered the mana personality, or is this Jung’s

personal universe? He relates no patient case histories, something which he

should be able to do, according to scientific standards.

Is this what practitioners of active imagination report? If not, then

active imagination, properly conducted, is better described as a spiritual

exercise aiming at relieving oneself of worldly concerns and maintaining a

wholeness of personality. Among the Christian mystics this method was known as

‘discursive meditation’. It was an exercise of the soul, meant to maintain focus

on the spiritual path. Jung, on the other hand, says that active imagination

concerns the integration of the anima as the ‘transcendent function’. At this

point, according to Jung, emerges the Wise Old Man, and images of the Self.

Archaic images are activated, portrayed by Jung in the Red Book

(Philemon, et al.).

Therefore it ought to be possible to demonstrate that people who

practice active imagination actually do observe this encounter with the Self and

also experience the concomitant changes in personality that must take effect

when the ego is overwhelmed by an entity vastly larger than itself, something

which is experienced as traumatic, and as a psychological death. This is how

Jung interprets the ‘nigredo’ stage in alchemy.

If this is not what practitioners of active imagination report, then

we are forced to conclude that active imagination is either (1) a form of hoax,

a throwback to 19th century spiritualism/romanticism, or (2) the practitioners

are fooling themselves to think that they are doing active imagination whereas

they are really only playing with fantasies or are reformulating conscious ideas

(e.g., in the fabrication of short stories), or (3) that active imagination,

properly conducted, is an exercise of the soul, meant to maintain focus on the

spiritual path, to motivate the adept to keep to the narrow path in order not to

regress to material obsessions. Following the terminology of Christian mystics,

the soul is thus kept sufficiently whole, preparing it for the contemplative

stage. In the Cloud

of Unknowing (Wiki, here), an unknown 14th century author explains that the spiritual

path is to remain in a state of unknowing.

An example of number (2)

is when M-L von Franz criticized Wolfgang Pauli’s text involving a

piano teacher. She said that this is not true active imagination because the

unconscious isn’t involved in the formulation of the images, but, rather, are

metaphors of consciousness. Personally, I have been doing active imagination in

writing for many years, and my unconscious has again and again urged me to

continue with it despite the fact that I experience no dramatic “change of

personality”, according to Jung’s model. But it’s like the unconscious is

fond of those unconscious products, which are expressed in dreams as colourful

fishes in an aquarium, or flowers, paintings, etc. It seems as if other

practitioners, as well, fall short of expectations. There are no dramatic

incursions of the Self, in the way Jung portrays.

I doubt that active imagination has this powerful capacity of archetypal

integration that Jung claims. This was also the position of his own anima,

something which he relates in his autobiography. When Jung was painting images

the anima told him that this was art which he was doing. He reacted

strongly against this and argued that the anima had tried to mislead him, which

is a controversial interpretation. I submit that she made an opposite

evaluation, to balance out his conscious standpoint. Arguably, he overvalued

this activity, or had adopted a lopsided view of it, and the compensating factor

was activated. The unconscious compensates the conscious standpoint.

Art history contains movements, such as symbolism, surrealism, and expressionism, which allow expression to the unconscious, to a degree. Arguably, Jungian active imagination is really a form of art. Novelist often say that their characters take on a life of their own. They are not mere constructions of consciousness. Thus, it is not obvious that the artist’s or the novelist’s activity is essentially different from active imagination. This could explain why the Jungian form of active imagination seems to have no pronounced effect on personality. It is, after all, an art form. The argument of Jung’s anima could be correct. I hold that active imagination easily reverts to artistic creativity, if the creative energy is raised beyond the feeble energy levels where the spirit roams.

If there are no dramatic psychological encounters on lines of Jung,

i.e. if Jung’s followers do not regularly report that they have encounters with

the anima/animus, the wise old man, and the Self, which are certain to

destabilize the personality in a psychological way, then what remains of

Jung’s psychological form of spirituality? If vivid encounters with complexes of

type anima/animus regularly occur, along Jung’s directives, then people’s

experiences remain within the confines of Jungian psychology.

However, if people have other experiences of active

imagination (formerly known as discursive meditation) that do not lead to the

awakening of powerful psychological complexes, then it must be denoted a spiritual

path, perhaps on lines of ancient Gnosticism, Alchemy, Taoism, or a personal

path (which, in a sense, is the Gnostic way). I do not deny that the complexes

anima/animus et al. exist. But I question how relevant it is to have this

radical encounter with them, except that you have to remain on friendly terms

with your own unconscious to be successful on the spiritual path.

So my question refers to this problem. Can Jung’s psychology satisfy

the spiritual seeker? Can psychology really replace the spiritual path? The

answer is no if these powerful complexes cannot be called up in the

majority of seekers. This could explain why the are such dissimilarities between

Jungian psychology and the traditional spiritual disciplines. There is however

one author whose writings bear a distinct resemblance with Jung’s version of the

spiritual path, namely Swedenborg (Wiki, here).

Jung read all his works. Swedenborg talked to the spirits while spending time in

his garden. So did Jung, who talked to his spirit guide Philemon while taking a

stroll in his garden. Jung also talked to the anima in this way. Jung’s form of

spirituality, it seems, has a certain resemblance to Swedenborgian spiritualism.

As a matter of interest, Swedenborg’s garden

house, where he had many of his visions, remains standing, but it has moved

to Skansen, Stockholm (Wiki, here).

Without doubt, the anima, for example, can

appear in many different forms, such as a dream animal. The central question is

whether followers of Jung experience active imagination in the same graphical

way as Jung outlines, e.g., if they actually talk with the autonomous complexes

of the psyche, who then retort intelligibly. Do they experience transformations

of personality as a result of a row of such encounters with autonomous

archetypal complexes, according to the order: shadow – anima – mana personality – self? Or do personal case histories reveal other experiences of active

imagination than what Jung outlines? I suppose that in order to recapitulate

Jung’s specific archetypal series, it’s necessary to imagine oneself in that

setting, together with these specific archetypal figures, and go through the

stages consciously, as if it was a Gnostic initiation ritual. But one cannot

expect the psyche to produce such fantasies spontaneously. However, this is what

Jung claims will happen, as he says that the psyche is structured this way.

I conjecture that, in most cases, there are no overwhelming

personality-changing experiences that ensue from the practice of active

imagination. I do not reject the method, I just say that Jung’s description of

archetypal encounters seems to draw on his very personal experience, and not how

people experience it generally. What is characteristic of the spiritual

experience is the “Cloud of Unknowing”, and not an invasion of

archetypes. The invasive and delirious ideal should be toned down. No

psychological meltdown and acute crisis is called for. It can be detrimental,

the way in which people tend to view the charismatic leader as a role model, and

his personal individuation as exemplary, unto the border of madness. On the

other hand, the process of symbol formation is valuable, and we are deeply

indebted to Jung and M-L von Franz for their great contributions

in the understanding of symbols.

© Mats Winther (2010-2011)

Notes

1.

See also Winther, M. (2011). ‘The Complementarian Self’. (here)