The Complementarian Self

The complementary nature

of the Self

Abstract: The Self, representing the wholeness of the

psyche, has in different guises functioned as a role model for the individual,

throughout history. In the Christian era, the ideal of the spiritual individual

who is morally perfect (Jesus Christ), through its very

one-sidedness, created a reversal of its spirit into materialism. Psychologist

Carl Jung, renounced the ideal of perfection and proposed an ideal

of completeness. The article argues that the trinitarian spiritual ideal must

continue to play a role, together with a this-worldly (

quaternarian) ideal of

spirit, following the principle of complementarity as defined by physicists. The

transformation of Self is an ongoing process in the unconscious. The complementarian Self obtains as the goal of the spiritual path.

In medieval alchemy it corresponds to the hermaphrodite, and the philosopher’s

stone. The article diverts from Jung’s view of alchemy regarding the method of

approach to the unconscious.

Keywords: twofold Self, psychic structure,

complementarity, St Augustine, Wolfgang Pauli, trinitarian, quaternity, alchemy, Christ.

IntroductionThe complementarity principle is a concept

developed by physicist Niels Bohr (1885-1962) to deal with the

existence of two models which are both useful, but not directly reconcilable.

The principle of complementarity is indispensable to modern quantum physics. It

helps to explain many quantum phenomena, such as the dual nature of light. This

article aims to show that it is also indispensable to psychology, in explaining

the structure of the Self, in terms of analytical (Jungian) psychology:

Self. The archetype of wholeness and the regulating center of the

psyche; a transpersonal power that transcends the ego […] The

self is not only the centre, but also the whole circumference which embraces

both conscious and unconscious; it is the centre of this totality, just as the

ego is the centre of consciousness. (Sharp, 1991)

I employ the term “complementarian Self” (not “complementary

self”) to avoid confusion with certain everyday uses of complementarity.

For instance, in depth psychology complementarity is sometimes used in the

sense of

completion, the assimilation of a content which has previously been

lacking in consciousness. The principle of complementarity, according to

quantum mechanics, implies that the total information about an entity or system cannot

be obtained because the information is located in at least two complementary

qualities. Measuring one quality precludes measurement of the other. In some

experiments light acts like a series of particles and in other experiments it

acts like a wave, which is why neither of these descriptions is alone adequate

to explain the nature of light. If we try to explain light exclusively as a

particle phenomenon, certain wavelike characteristics must remain unexplained,

such as the fact that light can be polarized.

However, “light as

wave” and “light as particle” are wholly different phenomena,

and the two models are mutually exclusive. Physicist therefore accept that

light’s nature is

complementary, taking on a different appearance depending on

the experimental setting. The two models seem to contradict each other, and in

a traditional sense they are excluding each other. However, if kept distinct

and used interchangeably, these two models cooperate to provide a full

scientific explanation of the phenomenon of light. They fit perfectly together,

like two pieces in a jigsaw puzzle. Together they create a wholeness that can

provide the whole picture. Important to understand is that either of the two

sides in the complementary model is a functioning wholeness, in itself. For

instance, light as wave movement is a wholly viable explanatory model. The

problem is only that some empirical facts fall outside this

model, so it must be complemented.

Complementarity beyond physics

Thus, two physicists come to two different conclusions as to the nature of light. One says that it has particle nature whereas the other says that it has wave nature. The reason why they get different results is that they have set up their experiments differently. My argument is that depending on how we set up our “cognitive equipment”, we come to different conclusions as to the nature of the world and the nature of morality.

Physicist Abraham Pais

observes that “[complementarity] can be formulated without explicit reference to

physics, to wit, as two aspects of a description that are mutually exclusive

yet both necessary for a full understanding of what is to be described”

(Plotnitsky, 1994, loc.cit., p.73). Also Niels Bohr has discussed

complementarity beyond physics (Collected Works, vol. 10). In the Gifford

lectures (‘Causality and Complementarity’, 1948–1950) he suggested that

theologians make more use of the complementarity principle.

An obvious instance of this, I argue, would be the double nature of

Christ. The Athanasian creed says: “Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, is

God and

Man … Perfect God; and perfect

Man … yet he is not two, but one Christ.”

The Christ came to earth as wholly man through the Virgin Mary.

Yet the Christ is also wholly God. It seems contradictory. He cannot

be wholly human if he is wholly God at the same time. Yet, we cannot solve this

dilemma by thinking of Christ as two separate persons. He remains one person,

wholly divine and wholly human, neither less human because he has a divine

nature nor less divine because he has a human nature. The Christ is a

wholeness — one

phenomenon — whose full description calls for

two

incommensurable models. It conforms with the complementarity principle. If the

Christ is compared to light, his human nature would correspond to light’s particle

nature, whereas the divine aspect would correspond to the wave aspect. Light is wholly

material and wholly wavelike, yet it remains one phenomenon, not two separate

phenomena.

The Self of transcendencyTranscendence need not be

interpreted metaphysically, but could refer to the urge of transcending

worldliness. This model could also be termed

the Self of oneness. In

C.G. Jung’s explication of the Christ as a symbol of the Self

(Jung, 1979), he does not touch upon the double nature of

the Christ, but argues that Christ as a symbol of Self is flawed.

There can be no doubt that the original Christian conception of the imago

Dei embodied in Christ meant an all-embracing totality that even includes

the animal side of man. Nevertheless the Christ-symbol lacks wholeness in the

modern psychological sense, since it does not include the dark side of things

but specifically excludes it in the form of a Luciferian opponent […]

Psychologically the case is clear, since the dogmatic figure of Christ is so

sublime and spotless that everything else turns dark beside it. It is, in fact,

so one-sidedly perfect that it demands a psychic complement to restore the

balance […] A factor that no one has reckoned with, however, is

the fatality inherent in the Christian disposition itself, which leads

inevitably to a reversal of its spirit — not through the obscure workings of

chance but in accordance with psychological law. The ideal of spirituality

striving for the heights was doomed to clash with the materialistic earth-bound

passion to conquer matter and master the world. This change became visible at

the time of the “Renaissance”. (Jung, 1979, pp.41-43)

Jung’s view of the Self is based on

completeness. He views the

one-sided spiritual ideal of man as counterproductive.

If one inclines to regard the archetype of the Self as the real agent and

hence takes Christ as a symbol of the Self, one must bear in mind that there is

a considerable difference between perfection and completeness.

The Christ-image is as good as perfect (at least it is meant to be so), while

the archetype (so far as known) denotes completeness but is far from being

perfect […] Natural as it is to seek perfection in one way or

another, the archetype fulfils itself in completeness […] Where

the archetype predominates, completeness is forced upon us against all

our conscious strivings, in accordance with the archaic nature of the archetype.

The individual may strive after perfection (“Be you therefore perfect (…) as

also your Heavenly Father is perfect.”) but must suffer from the opposite

of his intentions for the sake of his completeness […] “Redemption”

does not mean that a burden is taken from one’s shoulders which one was never

meant to bear. Only the “complete” person knows how unbearable man is

to himself. So far as I can see, no relevant objection could be raised from the

Christian point of view against anyone accepting the task of individuation

imposed on us by nature, and the recognition of our wholeness or completeness,

as a binding personal commitment. If he does this consciously and intentionally,

he avoids all the unhappy consequences of repressed individuation. In other

words, if he voluntarily takes the burden of completeness on himself, he need

not find it “happening” to him against his own will in a negative form.

(ibid. pp.68-70)

Jung is correct in saying that completeness and perfection (oneness as

emptiness) are mutually exclusive. His Self ideal is chiefly

this-worldly.

On the other hand, the Christian ideal is lopsided toward otherworldliness and

the ascetic. The latter form of wholeness may remain intact because it avoids

being rent asunder by internal conflict. Wholeness can be maintained because the spiritual

Self ideal implies not partaking in the world, instead to pass it by (“Jesus

said, Be passersby.”, Gospel of Thomas, 42). The man who partakes in the

world will inevitably become soiled, whereas the man who stands above it may

remain whole. However, Jung argues that the man who subscribes to the ideal of

perfection will inevitably fall into the pit which represents his dark side. After all, it

has not been integrated in his personality, but remains a negative factor in

the unconscious. Jung, however, really refers to the effects of the Christian

ideal on the general citizen who takes part in temporal life. Should he adopt a hypocritical attitude, he will inevitably fall prey to his own shadow. Arguably, Jung’s

analysis is not valid for unworldly man, who has accepted suffering and who stands apart

from the world. He cannot be called a hypocrite since the psychic

opposites are not active within him. Thus, he is capable of remaining truly whole.

The Self of completeness

According to Jung’s ideal of Self a

man should be capable of harbouring irreconcilable opposites activated as a consequence of him

partaking in the world. The powers of consciousness must be so developed that the integral parts of personality may remain collected, which include instinctual and dark

aspects of psychology. In this manner the dark sides will remain within

conscious command. On the other hand, should they remain unconscious, they will assume an overly

destructive form. One way or the other, the repressed content will come to

revolt against a fraudulent conscious standpoint. Jung’s understanding makes

much sense, and his conclusions build on clinical material. Yet, arguably, not many people are capable of such a feat, let alone

integrating the shadow and admitting to one’s own faults. That is known as “losing

face” among many an ethnic

group — blame should preferably be cast on

others.

Jung’s Self is associated with the quaternity, whereas the Christian

Self is

trinitarian. The quaternarian Self, being this-worldly, harbours many

opposites. It is beautiful and good, but also demonic and fearsome.

Like all archetypes, the Self has a paradoxical, antinomial character. It is

male and female, old man and child, powerful and helpless, large and small. The

self is a true “complexio oppositorum”, though this does not mean that

it is anything like as contradictory in itself. It is quite possible that the

seeming paradox is nothing but a reflection of the enantiodromian changes of the

conscious attitude which can have a favourable or an unfavourable effect on the

whole. (ibid. p.225)

As Jung realizes that these two Self models (the this-worldly versus the

otherworldly; the complete versus the perfect; the antinomial versus the empty;

the quaternarian versus the trinitarian) are mutually exclusive, he concludes

that his quaternarian model is the only right one, and declares the transcendental

model as obsolete. This he does without having refuted the latter. Rather, he has merely shown that

this-worldly application of the trinitarian model doesn’t work. Jung’s thinking

is curiously Hegelian. He thinks in terms of antinomies capable of synthesis. If

they aren’t capable of synthesis, but remain contradictory in themselves, then

logic says that either one is false. Against this, Plotnitsky explains that

complementarian thinking is profoundly anti-Hegelian (cf. Plotnitsky, 1994, p.11). My

argument is that this is the right place to apply complementarian thinking.

Both models are true, and both are necessary to fully represent the phenomenon

of the Self. Thus we arrive at a complementarian model which

includes irreconcilable opposites, and not only dialectical opposites. It stands

to reason that a truly exhaustive model of the Self should include both perfect

man and complete man. Arguably, Jung’s Self ideal does not provide the whole

picture. There is in him an inner conflict between the ideals of “complete

man” and “spiritual man”, as we shall see in the following

analysis of his dream.

The dream about kneeling before the highest presence

According

to Jung, the dream which he relates in the autobiography (Jung, 1989, pp.217-220), illuminated for him his relationship to Christianity, and

foreshadowed the writing of both “Aion” and “Answer to Job”. In this oft quoted

dream he bends down his head before the “highest presence”, but not

quite to the floor, as there is a millimeter to spare (cf. Jung, 1989, pp.217-20,

here). In Jung’s understanding the unconscious (the father) harboured great knowledge about

biblical exegesis, which would soon come to expression in “Answer to

Job”. His own modern psychotherapeutic standpoint is expressed as inferior to the

great exegetical cunning of his father. As David and Uriah later appear,

it seems like his father’s exegesis revolves around this particular story in the bible

(2 Samuel).

As the father appears as a clergyman, he

could be understood as a representative of the “Christian fatherly spirit”,

who thinks according to Church

doctrine — arguably, a way of thought that Jung underestimates.

His father’s interpretation, and the dream as a whole, concerns the role of

saintly man (Uriah) and why he must be regarded superior to the “lord of this world”.

In Jung’s own thought, man should attempt to approximate the Self as a

complexio

oppositorum, equally carnal and spiritual. But Uriah would approximate the

largely one-sided unearthly man, and not a

complexio oppositorum. Uriah, who refused order from David to

sleep with his wife (due to ongoing war), and

who lost his earthly life due to treachery, was practicing celibacy. Nevertheless,

in the dream, Uriah is superior to the sultan who lives in a circular gallery,

reminiscent of Jung’s symbol of the Self. He is seated in the middle of a

mandala where he speaks with counselors (about mundane matters) and philosophers

(about extramundane matters). Evidently, the sultan aspires to be equally

carnal and spiritual. Note that Jung associates the sultan with the “lord

of this world”, which is a well-known designation for the devil (cmp. the “monstrous”

Primal God Image, below).

Uriah is living far above the sultan, in a solitary (hermit’s)

chamber; a place “which no longer corresponded to reality” (i.e., the

realm of spirit). He represents the “highest presence”. Arguably, the

dream expresses that “spiritual man” is superior to Jung’s ideal of

the Self, which coincides with the understanding of great Christian

thinkers, such as St Augustinus, St Aquinas, and John Duns Scotus. The Christian

interpretation is expressed as vastly superior to Jung’s standpoint, in that his

father, the Christian Father-spirit, is intellectually superior. The dream

expresses that Uriah is superior to Jung’s notion of Self. Since, in Jung’s universe, nothing

other than God can be greater than the Self, he is bound to equate Uriah with

God. However, the dream probably expresses that saintly man (Uriah) is greater

than the man who manifests the completeness of the Self (the sultan). Uriah

represents crucified man, suffering man, the Man of Sorrows.

It could

be argued that Jung should have coped with the problem of “unearthly

man” versus “complete man”, and that his exegetic accomplishment

served as deflection from the critical

issue. This was the subject which was so “extremely important” in his

father’s lecture. The bible bound in shiny fish-skin, is really bound in the skin

of Christ, because he is

ICHTYS — the fish. Jung views the

bible as an “unconscious content”. This is logical, if the bible is

understood as the theological outpouring soon to surface. However, the bible could also

be understood at the objective level, or as the deep-rooted voice of our

Christian forebears, i.e. as the Christian thoughtway extant in the collective

unconscious. The roundish silvery scales of the fish skin that surround the

bible, could be understood as the sum of theological thought produced by Christian forebears.

In the dream Jung thinks of himself as an “idiot”. There is

really no reason for this if the dream is understood as a forthcoming engrossment

in the bible, a theological passion earlier overlooked by himself (after all, he

had other engagements in life). If he calls himself an “idiot”, it

means that his conscious standpoint, in some sense, is utterly wrongheaded. In

his own interpretation, he does not address this forceful expression of

self-reproach.

Why could Jung not bring his forehead quite down to the floor? Arguably, it foreshadowed that he would never come to bend to the message of this dream,

which is to regard spiritual man as the highest presence. He would not completely

yield, but persist in his standpoint that completeness is the ideal. He

would only bend to the message of God thus far, a millimeter to spare, in order to evade the demands of individuation at this very crucial

point — to fool

God himself, as it were. Arguably, this symbol derives from concepts of

electricity. A millimeter air between the poles will prevent contact, as no

transfer of energy can occur. This millimeter of air is really an abyss. Sometimes

it just doesn’t click, despite great intelligence and understanding. Had he touched the

earth, the electric current would have

entered his head, and the coin finally dropped. I make

the following interpretation: it is foreshadowed that

Jung will refuse to yield to pious man as an ideal. However, he knows well

not to turn a deaf ear to the spirit, so he will bend down in obeisance.

The complementarian Self

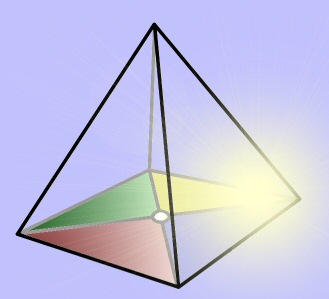

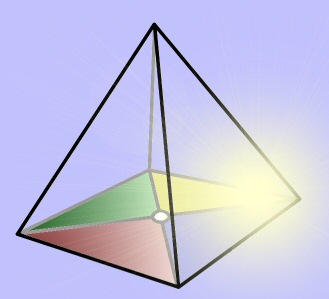

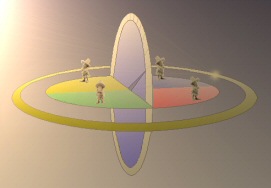

This is a schematic representation of above dream, which shows the

structure of the Self. Uriah is located at A and Akbar at B. To Jung, the

horizontal

scene — the circular room with the sultan in the

centre — represents

the Self. But also the vertical representation belongs in the full picture. The

gradient from light to dark illustrates the fact that the Self is only partly

conscious. See also the upmost image of the pyramid, where the horizontal

region suggests immanence as it has extension in space. It harbours many

opposites whose focal point is the

Self of completeness. In the horizontal region

compensation is

the major principle at work to balance the opposites, which are brought to

compensative harmony. The apex of the pyramid, which focuses in a point,

symbolizes the

Self of transcendence. An ideal point has no extension in

space. It illustrates the spot “which no longer corresponded to reality”,

where Uriah is located in Jung’s dream. The vertical extension indicates that

the two models are mutually exclusive (Akbar and Uriah as complementary

opposites), but are brought to complementarian harmony. In this model of the

Self, A and B (Uriah and Akbar) may complement each other so that a lopsidedness

need not occur. The historical lopsidedness in the medieval Christian

civilization has made the

Self of completeness (the sultan; the lord of

this world) stand out as too dark a character. The sultan is not that bad,

granting that he is ambivalent.

In all major religions we

find a Self ideal that corresponds to the ascetic and world-weary man: monks and

nuns, recluses, hermits, wandering

sadhus, self-penitents,

yogis, and contemplative mystics. Wherever

we look, the idea of the holy man resembles very much the traditional Christian

ideal, the ascetic who rejects the world and searches perfection according to an ideal condition of personality, void

of all commotion. Jung’s theory does not account for the fact that this is how

the Self has empirically manifested itself throughout history, the total number

of devotees vastly surpassing the sum of “enlightened sultans” in

world history. One cannot account for this enormous devotion in all higher

civilization by explaining it away as the neurotic consequences of a warped

worldview; a misunderstanding of the true constitution of Self or a misconception of the

true nature of God. The empirical facts about human psychology tell us that the Self manifests in two ways. Besides a yearning for completeness there is a longing for transcendence, for transcending the terrestrial turmoil, in both its inner and outer aspects.

Complementary paths of individuation

Jung says (my emphasis):

Individuation cuts one off from personal conformity and hence from collectivity. That is the guilt which the individuant leaves behind him for the world, that is the guilt he must endeavor to redeem. He must offer a ransom in place of himself, that is, he must bring forth values which are an equivalent substitute for his absence in the collective personal sphere. Without this production of values, final individuation is immoral and — more than that — suicidal […]

The individuant has no a priori claim to any kind of esteem. He has to be content with whatever esteem flows to him from outside by virtue of the values he creates. Not only has society a right, it also has a duty to condemn the individuant if he fails to create equivalent values (1977c, pars.1095f).

A real conflict with the collective norm arises only when an individual way is raised to a norm, which is the actual aim of extreme individualism. Naturally this aim is pathological and inimical to life. It has, accordingly, nothing to do with individuation, which, though it may strike out on an individual bypath, precisely on that account needs the norm for its orientation (q.v.) to society and for the vitally necessary relationship of the individual to society. Individuation, therefore, leads to a natural esteem for the collective norm, but if the orientation is exclusively collective the norm becomes increasingly superfluous and morality goes to pieces. The more a man’s life is shaped by the collective norm, the greater is individual immorality. (1977b, para.761)

If our vantage point is the Self of completeness, the above definition of individuation is undoubtedly correct. Nevertheless, it’s easy to think of examples when this definition doesn’t hold water because we cannot always chime in with ruling ideology. My conclusion is that Jung’s definition falters despite being correct and complete. As it isn’t sufficient to make an adequate definition of individuation, it must be regarded a complementary aspect. As the Self consists of a complementary pair, so must individuation be expressed by two complementary paths.

The theory of individuation stands only on one leg, because the reclusive way of individuation is missing. Jung took exception to the secluded and eremitic ideal as formulated in the Middle Ages, often denoted as ‘imitatio Christi’. This is the reason why he keeps so devotedly to a this-worldly ideal of Self. Nonetheless, it has awkward consequences. The individual cannot sing in unison with the collective during a time when the latter has become neurotic and follows evil and destructive ways. The Self must be viewed as complementary. There exists also a path of transcendency, complementary to the the path of temporality. Arguably, the rejection of the ways of the world is wholly consistent with individuation.

Jung’s view of individuation runs into difficulties. Although correct, it needs another correct definition as a complement. According to Jung, adaptation to the collective is essential to individuation. The problem is that all the late manifestations of culture are neurotic. It is a notorious theme in fairytales interpreted by

Marie-Louise von Franz. The consequence is that the individuant must needs contract the neurosis of the collective. As the individual adapts to the conflicted psyche, it becomes absorbed, to a degree. We also know that Jung, true to his view of individuation, made an effort to adapt to the Nazi collective. From what I have gleaned, he traveled to Germany and held speeches. He assumed overall responsibility for the Zentralblatt für Psychotherapie, a journal known to have published content that had Nazi flavour. Until 1939, he maintained professional relations with psychotherapists in Germany who had declared their support for the Nazi regime. He believed, as Christian missionaries always did, that evil could be turned to good.

Jung has been subjected to much critique for his standpoint of adaptation toward the Nazi regime. This does not mean that he believed in the Nazi system. His writings are essentially anti-fascist. But any attempt to adapt to an awfully pathological collective is doomed to failure. Arguably, he should have adopted the stance of the recluse who takes exception to the social collective, thereby holding off its neurosis. The way in which Jung behaved is predicated on his morally ambivalent Self ideal, symbolized by sultan Akbar in his dream. He really believed in the validity of evil, and that archaic and vulgar Nazism, as an upheaval of the collective unconscious, could be harnessed and reformed in conscious light. He theorized that evil must be integrated and put to good use, thus divesting it of its autonomous energy. Arguably, that’s why he dealt with the Nazis, up to the time that the war broke out. We know that he viewed the movement in symbolic terms as the resurgence of the pagan deity Wotan. The pagan mentality had been repressed and was now coming to life again. It represented a compensatory reaction against the spiritual one-sidedness of Christianity. The only right thing to do was to consciously adapt to it.

This all comes out of his theory of the relation conscious-unconscious. His standpoint was both well-meaning and theoretically compelling, but he was mistaken, because the Nazi worldview proved exclusively destructive. Arguably, there is something amiss with his view of the Self and of individuation. It focuses on integration, but doesn’t take the divisive force into account.

Negation plays no role in his system. I have instead argued that the upsurge of Nazism and warfare was an expression of Thanatos and destructivity for its own sake (Winther, 2012,

here). The divisive force, Thanatos, also comes to expression in reclusive individuation, as

mors voluntaria. The individuant effectively divides his universe and decides to stand apart from the world.

The pillar saint, perhaps the most radical form of asceticism, can be said to represent the complementary form of individuation. Jung was averse to pillar sainthood, because his view of the Self was essentially this-worldly. The notion of transcending the rumpus of the world was foreign to him. Of course, the pillar saint is a rather extreme phenomenon. Not all recluses in history went to these extremes. Yet it finely illustrates my point. Modern people tend to look with scorn at the figure of the pillar saint, who appears narcissistic, as he is elevating himself and placing himself on a pillar. But this is a projection, because it is really modern people who are prone to narcissism. In fact, the saint is showing his own wretchedness to everyone. He is not sitting there like a king in royal garment, but as the Man of Sorrows fastened on the tree. It is really a form of ‘imitatio Christi’. The pillar saints were anything but narcissistic. They weren’t elevating themselves, rather, they were punishing and demeaning themselves. It was like being nailed to a cross, hence a form of self-mortification. Traditional Christianity has always resisted narcissism, and spoken out against vanity, self-conceit, etc.

The Stylites spent years of their lives sitting on a

pillar. [1] St Simeon Stylites was disgusted with the world and wanted to distance himself from it. Luis Bunuel made a film about him, “Simon of the Desert”, in which the devil, in the form of a beautiful woman, subjects the saint to temptation. Evidently, Bunuel identified with the stylite. He was fed up with the superficial ways of the world and wanted to climb a pillar. Much like the pillar saint, he experienced that external reality was in the process of invading his private world, making him neurotic, too. So he wanted to escape the world. This was how Bunuel felt in face of popular culture, that annoyed him immensely. In Jung’s dream, Uriah is highly elevated, assuming a role similar to the “pillar saint”.

Pauli’s world-clock

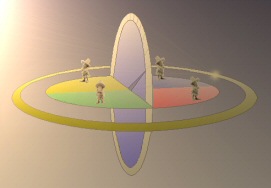

The image illustrates physicist Wolfgang Pauli’s vision of a

world-clock. It consists of a vertical and an horizontal circle, having a common

centre. The horizontal circle consists of four colours. On it stand four little

men with pendulums. The vertical circle is blue with a white rim. A pointer

rotates upon it. The “clock” has three rhythms. The pointer circulates

32 times faster than the horizontal circle, which represents the middle pulse.

Each revolution of the slowly turning outer golden ring, which was earlier

black, corresponds to 32 revolutions of the horizontal circle. The clock is

supported by a black bird (missing in the picture). The vision made a deep and lasting impression on the

dreamer, an impression of “the most sublime harmony” (cf. Jung, 1980,

p.203) (image by me).

Jung says:

[The] figure tells us that two heterogeneous systems intersect in the Self,

standing to one another in a functional relationship that is governed by law and

regulated by “three rhythms”. The Self is by definition the centre and

the circumference of the conscious and unconscious systems. But the regulation

of their functions by three rhythms is something that I cannot substantiate […]

We shall hardly be mistaken if we assume that our mandala

aspires to the most complete union of opposites that is possible, including that

of the masculine trinity and the feminine quaternity on the analogy of the

alchemical hermaphrodite. (ibid. p.205)

Jung argues that “two heterogeneous systems intersect in the Self”.

That sounds very good in my ears as it can be interpreted in terms of

complementary opposites, especially since Pauli belonged to the Copenhagen

school to which the concept was central. Since the mandala, according to Jung,

is a symbol of the Self, it is logical to interpret the image as two Self

symbols intersecting. However, what Jung refers to as “two heterogeneous

systems” are the conscious and the unconscious systems. Accordingly, the

latter is feminine, has blue colour, vertical extension, and is

associated with the number four (ibid. p.213). Consciousness is masculine and connected with

the number three. The idea is that the image represents two psychic systems unifying to manifest the alchemical hermaphrodite. But there is a

logical contradiction in that the horizontal mandala, representing

consciousness, is clearly fourfold, and not threefold.

The horizontal circle is a typical Jungian mandala with its four functions,

beleaguered with opposites, representing the notion of the Self. The vertical

mandala is empty, save for the pointer, and has the colour and the shape of the

heavenly arch. It would represent the trinitarian Self since vertical extension relates

to transcendence. It is stationary (at least, it is stationary in the vertical

extension), suggesting permanence, an existence beyond the world of flux. If the

upper partition relates to the superstratum of spirit, the lower partition would

signify the substratum of matter (as such). The vertical mandala is simple,

pointing in

one direction at a time, thus conforming to the ideal of the

Christian mystic or Zen buddhist, namely emptiness and

oneness. The

horizontal layer is like

terra firma on which the little men can stand, suggesting immanence. It

is revolving horizontally, in its own

extension — the worldly abode of the

psyche is temporal and always in flux. It is partitioned into front and back,

corresponding to conscious and unconscious. The horizontal mandala is multifarious, and

diverse things are going on, expressing

completeness. The latter type of

wholeness is similar to a light that beams in all directions, whereas the oneness

ideal focuses in a laser beam. Yet the pointer of the blue mandala will

eventually point in all directions,

too — it’s just that it does it one at a

time.

Thus, two independent wholenesses intersect to create a

three-dimensional wholeness, a perfect symbol of the complementarian Self. The

golden ring circulates around the double mandala to emphasize that the whole

construct constitutes

one wholeness made up of two intersecting wholenesses, or Self models.

The ring has gone from black to gold, because illumination follows after a period of

darkness. Such a ring is called

nimbus and is used to denote divinity.

It is seen surrounding the heads of gods and saints in artworks of all major

religions.

Pauli’s dreams and thoughts often revolved around the

problem of three and four. He was influenced by Jung’s notion that three is an “incomplete

wholeness”. However, in this context I think it denotes the Self of

transcendence. The three-rhythm of the world-clock is an apt symbol of the

transcendental spirit, especially as time is invisible. Yet, time also denotes

the temporal sphere and the terrestrial spirit, as evinced by the

cabiri (chthonic deities) with pendulums. Therefore

three-rhythm

could be understood as three + rhythm, 3 + 4, heavenly

plus temporal, which is the theme of the vision. Pauli often said he wanted to

reconcile “Christ and the Devil”, but he tended to project this

problem on physical science, or on our biological nature as representing the

number four. However, I think it better compares with the dream about Uriah and

Akbar. Yet, this symbol could also be pertinent to the mystery of

matter. [2] The dream about BohrI

suggest that Self-complementarity holds the key to many of Pauli’s dreams. On

Oct 1, 1954, he dreamt that Bohr explained to him that the difference between

v

and

w corresponds to the difference between Danish and English. Bohr said that

he should not just stick with Danish but move on to English (cf. Meier, p.143).

Although English is a Germanic language, like Danish, it has borrowed heavily

from Latin and French. Moving on from Danish to English suggests speaking a “complementary”

language. Bohr, as the father of complementarity, personifies the principle of

complementarity. That’s why he advises Pauli to move on to the complementary

pair:

w, pronounced “double-you”. Indeed,

double-you

would imply

double-self. In the Hebrew language,

letters have always been used to denote numbers, especially in Cabalistic

mysticism, but are nowadays used only in specific contexts. Hebrew letters are

still used to denote dates, grades of school, and other listings. Pauli and

Bohr, since they were both Jewish, ought to have known this. The letter

v (

vav) is

the sixth letter and therefore has the numerical value of 6. Two

vavs (

vv) is in

traditional number mysticism calculated as

6 + 6 = 12. Thus the

w

in the dream equals 12, which is the product of 3 and 4, symbolic of the

resolution of the problem that had haunted Pauli. The sixth letter

vav, however,

can alternatively be represented by

w, so the symbolic meaning of

w is

analogous. The pronunciation of

v in Danish also corresponds to

w in

English. Hence

v would symbolize the Self, and

w symbolize the Self in its

complementary version. This interpretation is bolstered by Jewish tradition,

according to which

vav (

v,

w) represents the connection between “heavenly

and earthly matters”, while it is also the “number of

man”. [3] It coincides cogently with the definition of the Self.

In a theological reading, the image of man as the connecting force between

heaven and earth is symbolic of Christ.

The problem of 3 and 4

According to M-L von Franz (1974), the whole numbers aren’t

mere signs for quantities. Each number signifies a wholeness of its

own — qualitatively,

that is. The number 3 is experienced as a three-wholeness, the four as a

four-wholeness, etc. Thus, the natural numbers may serve as different

models of the Self or as different models of the divine.

Jung’s god image, as expressed in “Answer to Job”, is quaternarian.

In a letter to von Franz (Nov 6, 1953) Pauli accounts for an active

imagination experienced by him. The letter was headed with the caption, “To

the sign of 6”, followed by:

2 × 6 = 3 × 4. To this was added the motto, “The professor

who shall reckon numerically” (cf. Lindorff, p.178). Again, Pauli grapples

with the problem of 3 and 4. He believed the solution lay in the number 12, as

the numerical product of 3 and 4, but he eventually became stuck. Lindorff says:

The number 12, in spite of its failings, had led Pauli to a more expansive

view of the

self, but he was still stymied. With frustration he wrote to von Franz, “Every correct solution (i.e., that corresponds to nature)

must contain the 4 as well as the 3. I found myself in an apparently

no-way-out situation: ‘I was cornered’, as the Americans say” […]

Pauli

had the intuitive feeling that the 3-4 problem could be solved

only by living the 3 and the 4 simultaneously — in other words, by

relating to the dynamic aspect of the Self. (ibid. pp.185-87)

The expression 3 × 4 symbolizes, in itself, the resolution of Pauli’s

yearning to arrive at a more expansive view of the Self. The sign of 6 is the

sign of man, as we learn from Revelation 13:18 (having to do with the fact that

man was created on the sixth day, etc.). It is the counting letter

vav in the

Hebrew alphabet, that can be said to symbolize the Self. Also in this case is

hinted at the motif of

2 × vav, that is,

w. I conjecture that

the above equation says:

the twofold Self is the solution.

“An ace of clubs lies before the dreamer. A

seven appears beside it.” (Jung, 1980, para.97)

Pauli discussed this dream with Jung. He came to view the black

crosslike shape as the “

shadow cast by the Christian cross — in

other words [the]

dark side of Christianity” (cf. Lindorff,

pp.53-54). It represents, I suggest, the Christian paradigm grown stale. That’s

what’s on the

table — his present state of Self, and of civilization. The 7

represents what shall come instead. It is the

materia prima, the

psychic generic substance, out of which the 3 and 4 shall emerge in the form of the

alchemical royal brother-sister pair. The number 7 is associated with the

materia prima due to the seven metals (gold, silver, mercury, copper, iron, tin,

and lead). These are reducible to materia prima, which, conversely, can generate

any of the seven metals. The metals are associated with the seven “planets”

(Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn). To associate the number

7 with the yet unknown problem of 3 and 4 is logical, although this

interpretation is uncertain.

The Primal and the Ultimate God Image

According to

Joseph L. Henderson, (1967, 2005), the

motif of transcendence is evident in documented rituals of initiation and in

the fantasies and dreams of patients. During a phase in the individuation

process there is a longing to transcend this world of particulars, and a

strong urge to transcend animal nature. Allegedly, the motif also plays a role

in the transcendence of group identity; to acquire a refined “apollonian”

spirit of order. His notion of “God Image” is equivalent to the Self

notion, and he outlines two aspects of the Self: the Primal God Image and the

Ultimate (Celestial) God Image. Although Henderson tries to accommodate this view of

the Self within Jungian confines, to me it’s evident that the Primal God

Image corresponds perfectly with Jung’s Self, whereas the Ultimate God Image has

the bearing of the Christian trinitarian spirit.

The Primal God Image stands for the individual experience of God. Henderson

exemplifies with an

ambivalent monster situated in the centre of a mandala, lacking limbs, but capable of benevolent wisdom (cf. Henderson, 1967, p.226). It embodies the

opposites good and bad, creation and destruction, male and female, etc. It

brings to mind Jung’s youthful dream of an underground deity in the form of a

one-eyed phallus (cf. Jung, 1989, p.12). As a complement to the monstrous Self,

Henderson posits the Ultimate God Image. In a fantasy, a patient returns to

the Christian Godhead, in improved form, after a dangerous but rewarding

encounter with the Primal God Image (cf. Henderson, 1967, p.206ff). Henderson interprets

the initiation in the celestial mystery (the ascent) along lines of Mircea Eliade. Initiation rites in primitive society serve the purpose of

transcending a former and more primitive identity, to achieve a higher grade

of culture. This implies a gradual abatement of group identity. The person who

has undergone these rites has transcended the secular condition of humanity.

Intermediate God Images

Such aspects of primitive

sociology, however, cannot account for humanity’s enormous spiritual passion of transcendency. I maintain that Henderson has, by a

furtive reintroduction of the trinitarian transcendental God Image as an

intrinsic aspect of individuation, really broken with Jung’s view of the Self.

Jung viewed the Christian spirit as chiefly an impediment to individuation,

although certain individuals must remain under the auspices of Christianity due

to constitutional factors of personality. The Primal God Image has properties of

Mother goddess, whereas the Ultimate God Image corresponds loosely to the

fatherly aspect of divinity. Fatherly spirituality revolves around transcendence

and the breaking free of bonds in whatever form. As Jung’s Self notion lacks the

trinitarian complementary element (the transcendent presence of Uriah),

spiritual emancipation becomes subordinate to the assimilation of archetypal

complexes, and more generally, subordinate to the involvement and identification

with archetypes and the mirages of the world. This could lead to a dependency on

the unconscious and on psychology, as such. The effects are similar to

a mother complex. It involves putting a naive trust in the unconscious psyche, namely to

view it as a good mother, expecting her to lead the way through dark woods,

securely to Avalon, the island of legend. There is sometimes a tendency to

romanticize the archetypes; to intentionally identify with them, along lines

of New Age. It cannot be ruled out that such a mother-child relation with the

unconscious is sometimes of the good, but it does not bespeak objectivity in

face of the uncanny ambivalence of the unconscious. The this-worldly ideal of

spirit, which is almost of the Celtic hue, where the spirits are always proximate, is

deep-rooted in Jungian psychology. It is antithetical to the inner call of transcendency, to remove all distractions and to empty the

self of all particulars; to

unshackle personality from the realities of everyday life. In the end, pagan mundaneness will keep the subject in psychological

fetters, save for those blissful individuals who, by nature, belong in the lush

Celtic forests.

Two Cities

The notion of two sides to personality accords with St Augustine’s view, as explicated in his masterpiece “City of God” (cf. Wiki,

here). Eugene TeSelle says:

In Augustine’s thinking [the metaphor of two cities] meant differentiating between two modes of life and two concrete communities which he called the earthly city and the city of God, expressed in, but not identical with, the state (or civil society) and the church. Before he arrived at that position, however, he understood the duality (not dualism!) in a variety of other ways. At first he thought it possible to live fully in both cities at the same time, to be bathed in the divine light yet active in the material world. Then he came to the conviction that this is impossible under current conditions — that we are so firmly enmeshed in the sensory world that we can be citizens of the city of God only through faith and hope, or through the momentary ecstasy that he called “alienation” from the world of the senses. Duality, in other words, may be built into the human situation. (TeSelle, 1998, p.xi)

Jung, as we know, thought it possible “to live fully in both cities at the same time”, according to his ideal of an integrated life. Although Augustine rejected this view, he emphasized that some may change citizenship. Says TeSelle:

Thus the term “city,” [refers] metaphorically to much more than the physical city. The two loves and the two societies which they constitute transcend all empirical states and organizations. That is why Augustine emphasizes that both angels and human beings can belong to each city, so there are two cities, notifier (ciu.dei XII,1). In the case of human beings, furthermore, the duality between the earthly city and the city of God is not fixed or final; all human beings are born citizens of the former, while some may be reborn into the latter. (ibid. p.22)

The manifestation of the Self

The laws of quantum physics allow us to get a more exact measurement of

either the momentum

or the position of a particle. Those two

qualities cannot be exactly measured at the same time (cf. Wiki: ‘Complementarity’,

here).

By analogy, should the complementarian Self become manifest in reality, in a real individual, it will appear as either

complete

or

transcendental, either as Akbar or Uriah. No person may

manifest the two ideals at the same time.

The trinitarian longing after transcendence represents an inner urge to

transcend the worldly, in order to bring the soul to stillness. The notion did

not appeal to Jung, whose idea of the spirit is experiential (kataphatic). He

rejected the view of

John of the Cross (1542–1591), who said

that the contemplative shall enter the

dark night of the soul, to leave

room for the infusion of God’s

spirit. [4] Yet,

both persons were right in their own way.

Jung followed the completeness-ideal and liked to think of himself

as a modern Merlin. Krishnamurti (a very Christlike person, but nothing like the

historical Jesus) followed the transcendental ideal. Both individuals had a very

different view of things. Krishnamurti refused any psychological, inner,

evolution or “becoming”, and said that any movement away from

inner emptiness is an escape. Despite their mutual irreconcilability,

both perspectives carry a great deal of truth, because it is the truth about

the Self. (Remember the principle that either of the two sides in the

complementary model is a functioning wholeness, in itself, although neither of them is quite

sufficient to describe reality.) Both persons, believing that they had found the

right path to the Self, attempted to realize the Self, not knowing that the Self is

complementarian (complementary).

What does this mean? It means that both persons were

right but also utterly wrong, because their vision of the Self does not

include its complementary. Krishnamurti manifested a Christlike ideal, whereas

Jung manifested a modern Merlin. Since they both portrayed a

vision of the Self that is a wholeness in itself, it fails to epitomize the

whole truth about the Self. To the extent that they identified with the Self,

they also estranged themselves from its complementary opposite. To manifest the

Self is to become alienated from the Self. Likewise, the quantum phenomenon can only

manifest either of its two complementary opposites. The other opposite is

discarded. When the holy man Krishnamurti manifests the Self as a living guru,

he has discarded his complementary. As a consequence, he alienates himself from the Self

while making it manifest. Accordingly, Jung observed that the saintly practice

of ‘imitatio Christi’ alienated religious devotees from the Self of

completeness. History is replete with tragic victims of ‘imitatio Christi’. On

the other hand, the ‘imitatio Merlini’, in the way of the modern paganist, alienates

the subject from the Self of transcendence, the consequences of which I have

discussed above. The conclusion is that it is a mistake to throw out the

complementary opposite, because it inevitably leads to identification with the

Self.

The hermaphrodite

An alchemical image of the hermaphrodite (

rebis) as the fulfilment

of the opus (from Rosarium Philosophorum, Univ. of Glasgow Library,

here). Rex and Regina,

or Sol and Luna, corresponding to sulphur and quicksilver, have reemerged from

the darkness of

nigredo as a Janus-faced creature, the

rebis. To Jung it

represents the realization of the Self as conscious and unconscious conjoined.

The problem with such a view is that it cannot happen in reality,

since psychic structure remains largely the same. However, his argument revolves

around archetypal symbolism. The advancement is expressed in terms of a

superlative archetypal symbol, although a conjunction has occurred only to a

relative degree. It depends on the fact that the archetype of the

conjunction is activated during the process when contents are

integrated with consciousness. Although Jung’s explanatory model is logical, it

functions not as well with other symbols of the process.

The royal brother-sister pair both emerge from the

prima

materia or

massa confusa, which in Jung’s understanding is symbolic of an undifferentiated

unconscious, often associated with the tailbiting

snake — the

uroboros. It has been understood as the instinctual and undifferentiated state of the

Self — the uroboric Self. According to Jung (1980), the brother-sister pair represents

the feminine and masculine aspects of the prima materia. Thus, it is not

evident that the male aspect of royalty, the sun, is equatable with

consciousness, or the heroic ego. Rather, it is a symbol of the spirit, which is

also evident from the texts. The rebis symbol could alternatively be interpreted

as the result of operations performed on the Self, during which the Self complex, as

such, is transformed, and not the psyche as a whole. It would symbolize the

complementarian Self and its constituent parts of two irreconcilable

opposites — the sun-spirit of sulphur and the moon-spirit of quicksilver, i.e., the Self of

transcendency and the Self of completeness. The alchemists themselves seemed to

reason along similar lines. Jung says:

For the alchemist, the one primarily in need of redemption is not man, but

the deity who is lost and sleeping in matter. Only as a secondary consideration

does he hope that some benefit may accrue to himself from the transformed

substance as the panacea, the medicina catholica, just as it may to the

imperfect bodies, the base or “sick” metals, etc. His attention is

not directed to his own salvation through God’s grace, but to the liberation of

God from the darkness of matter. By applying himself to this miraculous work he

benefits from its salutary effects, but only incidentally. (Jung, 1980, p.312)

Jung argues that the alchemist’s standpoint is largely a

misunderstanding of the nature of his work, due to projection of the alchemical

opus on matter. The redemptive project really concerns the artifex himself:

The darkness and depths of the sea symbolize the unconscious state of an

invisible content that is projected. Inasmuch as such a content belongs to the

total personality and is only apparently severed from its context by projection,

there is always an attraction between conscious mind and projected content.

Generally it takes the form of a fascination. This, in the alchemical allegory,

is expressed by the King’s cry for help from the depths of his unconscious,

dissociated state. The conscious mind should respond to this call: one should

operari regi, render service to the King, for this would be not only

wisdom but salvation as well. Yet this brings with it the necessity of a descent

into the dark world of the unconscious, the ritual […], the perilous adventure

of the night sea journey, whose end and aim is the restoration of life,

resurrection, and the triumph over death (p.329) […]

Resulting as it did

from the advice of the philosophers, the death of the King’s Son is naturally a

delicate and dangerous matter. By descending into the unconscious, the conscious

mind puts itself in a perilous position, for it is apparently extinguishing

itself. It is in the situation of the primitive hero who is devoured by the

dragon. (ibid. p.333)

True, in Splendor Solis (The Third Parable) the King is drowning in the sea

and he is calling out for help. However, the text does not relate that an heroic

individual dives into the sea to help him. Instead, when the morning comes, the

King has wondrously resurrected. There is no reason to assume an heroic and

self-destructive action on part of the artifex, especially not at the beginning

of the process. A change of attitude would suffice to rescue the King; to

tone down outer life and to direct libido inwards. Arguably, if the King is lost in forgetfulness it calls for an improvement of the alchemist’s spiritual understanding. The profane alchemist believed that alchemy was equal to

laboratory work; the

arcanum merely a substance to be produced in

the retort. In such case the spirit is wholly projected onto matter. It is

therefore captive in matter, from where it is calling for help. If that’s the

case, saving the alchemical King from drowning in the sea means to partly

withdraw the projection from matter, leading to a symbolical and

celestial understanding. It cannot be achieved by allowing ego

to be dissolved in the unconscious, on the heroic interpretation. The Splendor

Solis goes on to describe how the body of a man with a golden head is laid

waste, in order that he “might possess abundant life” (The Sixth

Parable). In the Seventh Parable an old man becomes young again by having

himself cut up and boiled. The decapitated King is not the

ego — it is the Self. Alchemy is

Ars Trasmutatoria. Yet, Jung tends to interpret alchemy according to the

heroic struggle of the ego, although the dying and resurrecting King represents not the

ego, but the Self. The destruction and recomposition of the Self, as a

semi-autonomous process, does not seem to fit into Jung’s scheme (cf. Jung, 1977, p.371). Arguably, since he

wanted to accommodate alchemy within his psychological paradigm of “direct

confrontation and integration”, he tends to overlook the empirical

facts. Alchemical texts seem to

revolve around another theme, namely to

assist the processes of Nature (see the extract

from Splendor Solis below).

The argument that I put forward, that the

alchemist’s work really revolves around the transformation of Self, gives

the issue a different slant. Since the effect on consciousness is indirect,

participation does not require a radical crisis of the ego, involving its

dissolution in the unconscious. It tallies better with the recurrent idea of the

red elixir, or the wonder-working

lapis, as the end product of

the process. The philosopher’s stone, as a panacea, has the capacity to transform and heal ego

and body, and to create even more wonders. Yet it seems

illogical to equate this ‘thing’ with the realized whole of the subject’s

personality, conscious and unconscious included. Arguably, it is better understood

as the renewed and reconstituted Self, capable of influencing the wholeness of

personality. The Self has awakened from a dormant stage and become active. It

would imply that the hermaphroditic rebis, as the goal of the process, is

realizable

in the unconscious, unlike the unrealizable ideal of psychic wholeness, in archetypal

form, on lines of Jung.

It’s now easier to understand why the artifex must heat the

alchemical brew slightly and leave it alone for a long time, merely controlling

the fire. The transforming process is to a high degree autonomous. He must add

the ingredients and provide only a little heat. It corresponds to a method of “heating”

by which consciousness directs its rays at the unconscious

massa confusa.

It is a focusing attention of sentient light, but not a strong light, and not too much of it. This

causes the content to slowly brew. Personality adds to the brew the divine sparks (the

scintillae) that are found in nature. According to Hortulanus, the stone arises

from a

massa confusa, containing in itself all the elements (cf. Jung,

1980, p.325). It is sufficient to itself. Rotation brings the elements in

motion, an apt symbol of a process that is self-feeding (i.e., a feedback

process). Accordingly, the

uroboros, whilst symbolizing the prima

materia, also denotes the alchemical opus as a whole.

The alchemical

belief that the redemptive work is performed on a divine

spiritus mercurialis (the Self) enclosed in matter can

be interpreted in psychological terms as the becoming aware of the Self (or more

precisely, the contents belonging to the Self). However, on such a

view, it’s not possible to interpret the process in terms of a reconstruction of

the

self — a renovation of its very

nature — since the Self is already defined as a psychic wholeness ready to be moved into the light. Nevertheless, a

process of renovation is apparently what the alchemical manuscripts seem to

describe, rendering a symbolic picture that is not quite comprehensible in

Jungian terms. In fact, Jung’s Self is only half the truth. It seems that it corresponds to

the feminine part of the brother-sister pair, to be united with its

complementary, in order to be reborn as the hermaphroditic

Self. [5]

In Jung’s view, the

conjunction is understood as the united

conscious and unconscious, something that is connected with dangerous inflation.

The process requires that the ego is dissolved in the unconscious to unite with the

Self, a demand that very few people are capable of or

prepared to go through. In that case alchemy is for a tiny élite

only. How many artificês have actually lived through such an extreme crisis at the very

edge of psychic disaster? The alchemist as daredevil, who

recklessly dives into the unconscious to do battle with the dragon, is not the proper view of alchemy.

The alchemists always repeat their dictum that the process proceeds

from the

one and leads back to the

one. It is the same thing,

but the first one is inferior and the second one is superior. The dictum concerns the

Stone. Such a notion is hard to understand in the light of psychology,

where the initial state consists of ego and Self as

two different

standpoints to be united. In my reading the alchemical gold,

i.e., the achieved

coniunctio in the form of the

hermaphrodite

or the

lapis, represents the reformed Self, as such. It is the

wonderworking Stone that will heal the soul, the body, and the world. Thus the ego

is indirectly affected by the transformed Self, which has emerged thanks to a process of Nature, with a helping hand from the Art. In

a sense the artifex is an “active bystander” who provides the right

conditions for the Stone to grow out of Nature, by itself. Salomon Trismosin (“Splendor Solis”) says:

[Quicksilver] is a material common to all metals; but it should be known

that the first thing in nature is the material gathered together out of the four

elements through Nature’s own knowledge and capacity. The philosophers call this

Material Mercury or Quicksilver. It is not a common mercury: through the

operation of Nature it achieves a perfected form, that of gold, silver, or of

both metals. There is no need to tell of it here: the natural teachers describe

it very clearly and adequately in their books. On this the whole art of the

Stone of the Wise is based and grounded, for it has its inception in Nature, and

from it follows a natural conclusion in the proper form, through proper natural

means […]

For this one must decoct and putrefy it after the manner and

secrets of the Art, so that by art one affords assistance to Nature. It then

decocts and putrefies by itself until time gives it proper form. Art is nothing

but an instrument and preparer of the materials — those which Nature fits for

such a work — together with the suitable vessels and measuring of the

operation, with judicious intelligence. For as the Art does not presume to

create gold and silver from scratch, so it cannot give things their first

beginning. Thus one also does not need the art of Nature’s own secret to possess

the minerals, since they have their first beginning in the earth […]

Through the secrets of the Art they can be made rapidly and manifested complete,

born from temporal matter through Nature. Nature serves Art, and then again Art

serves Nature with a timely instrument and a certain operation. (Trismosin,

pp.19-21)

It is obvious from the above text (which is rather typical) that the

process is highly autonomous (it “decocts and putrefies by itself”).

Yet it must constantly be nourished with the fiery element, because the

salamander thrives on fire. The artifex does not leave

the decoction alone to take care of other business. He takes part,

but in a more deferential way than how Jung portrays it. The artifex’s

attitude is similar to that of the Christian mystic. According to alchemical texts, piety plays a big role. It is this attitude which provides the fiery element, symbolic of the

energy that returns to the unconscious. To this is added meditations in some

form, which serve to search out the

scintillae of

physis.

My reinterpretation, however, does not refute Jung’s view of

alchemy. However, it affects the most important aspects, namely how to view the

relation with the unconscious, and the way in which the spiritual journey is

accomplished. To Jung it involves a radical transformation of consciousness,

including dangerous encounters with archetypal reality. To the alchemists,

however, it regards the radical transformation of divine Self, having an

indirect benevolent after-effect on life as a whole. But the ego is not the

foremost

beneficiary — it is God. In fact, Michael Maier, author

of the alchemical emblem book

Atalanta fugiens, says that at the end of

his grand

peregrinatio he found neither Mercurius nor the phoenix, but

only a

feather — his pen! (cf. Jung, 1980, p.431).

Complementation

Individuation in Jungian terms excludes the trinitarian ideal of individuation, which centers upon the reclusive life. After coming to terms with personal problems, individuation proceeds by way of assimilation of archetypal complexes. The strong focus on integration makes it insufficient as a method of relating to divine nature. To rectify this lopsidedness, I have suggested a notion of

complementation (Winther, 2012,

here). It would mean to put focus on the regeneration of the

unconscious, rather than the transformation of conscious personality. It is necessary to distinguish the operation from the traditional notion of integration of archetypal complexes. Integration implies that the autonomous archetype “sacrifices” itself for the benefit of the conscious world. It mirrors the self-sacrifice and dismemberment of the gods in pagan religion. However, in religious history sacrificial priest also make a reparational offering. To give life back to the gods was regarded as equally essential. In the modern era, it could take the form of pious acts that direct conscious focus onto the divine. Meditation and contemplation are ways to sacrifice sentient energy for the rehabilitation of the spirit, although non-commercial artwork is perhaps better suited for modern man. The individuant becomes more or less a seclusive. Such an surrender of sentient awareness is necessary for the growth and transformation of Self. I denote it

complementation, since I think of it as a slow process whereby the unconscious collects and constellates its nature, aided by a mild conscious focus. I submit that it corresponds to the alchemical symbols of

circular distillation and the transformations in the vessel.

Complementation does not imply that the unconscious is restructured according to the designs of the ego. On the contrary, it is a semi-autonomous process to which the ego contributes by providing energy, and by modulating the heat with an amount of intellectual understanding when it gets too hot, or increasing the heat by symbolic awareness, alternatively a contemplative focus. Thus,

complementation would mean the very opposite of ego control and psychic integration. The Self, or any other archetype for that matter, does not abide in the unconscious as a ready-made Platonic form. It is more organic than that. Normally, it needs time to grow in order to blossom out at a point in time, also on the historical scale. Jung points out that the

anima (soul complex) does not constellate in all ethnic groups. The anima is not generally present among the Chinese, which would depend on historic factors. Jung and von Franz hold that there is a complete range of historical personality types in a population, from Stone Age people, via the medieval mindset, to the modern individual. Von Franz relates that she once met with a Stone Age man who lived in the Alps, who walked about stark naked during the summer. He lived in unison with the brooks, the trees, and the animals. The reason why personality is thus rooted in the different ages of man would depend on the structure of the psyche. In a minor portion of the Western male population the anima never constellates. Combined with other genetic factors, the personality might turn out as a Stone Age man who chooses to live with Mother Nature. By example, the medieval laboratory alchemist is still alive and well in modern society. Such people have a fascination with chemical processes and crystal formations in the retort. Most people are unable to grasp the extent to which they enrich the chemical process with meaning. Because it is symbolically quite potent, the alchemists think that it

is the ‘quinta essentia’. Perhaps one could view them as medieval dwellers that happen to live in the wrong age.

Analogously, the Self as the alchemical hermaphrodite, or the

rebis, may constellate in a population. The process is slow, however, similar to the emergence of the anima. The alchemists argued that they were capable of speeding up the processes of nature in their own laboratory. It implies that the artifex is able to assist the constellation of the Self. Thus, complementation signifies a way of assisting nature’s work of archetypal constellation. It serves to speed up the process, so it doesn’t require a thousand years of efforts, via many generations.

The process would occur relatively independent of consciousness. It is coupled with a different attitude of personality. The greedy and gluttonous frame of mind, so typical of the ego, forms the basis of the psychological paradigm, whose central tenet is the assimilation of the unconscious. The ego thinks that everything in the unconscious belongs to “me”. The devouring capacity is denoted as the “synthetic function” in psychoanalysis. As soon as a content surfaces, the ego immediately appropriates it and claims that it has been conceived by the ego.

The ego is a dictator that enslaves psychic content. There exists a well-known fairytale motif of being “captured by the mountain”. In Scandinavian fairytales it is called “bergtagen” (lit. ‘mountain-taken’). Characters are captured by the mountain and swallowed by it wholly or partly. Occasionally they become stuck with their head or a limb. Sometimes they become stuck in a thorny thicket that surrounds the mountain, transfixed on the thorns. Fairytales depict psychic life from the perspective of the unconscious in order to compensate for the one-eyed conscious outlook. The evil mountain (glass mountain, golden mountain) portrays the insatiable over-extended ego from the viewpoint of the unconscious psyche. The covetous and egotistic attitude is severely criticized in religious teachings, not the least in traditional Christianity, since it is inimical to the spontaneity and naturalness of psychic life. The ego should give glory to God and refrain from glorifying itself by taking credit for all the blessings that are bestowed upon it. Vainglory and self-worship is condemned. However, if the psychoanalytic paradigm is taken to its extremes, in terms of the integrative effort, as in Edward F. Edinger’s psychology, the ego has become an evil mountain, inimical to spiritual and instinctual life. In Christian theology, pride and arrogance is destructive to the workings of the Holy Spirit in the soul.

Complementation, which I connect with ‘circular distillation’ in medieval alchemy, builds on a different attitude of personality. The ego rids itself of its typical illnesses, namely covetousness and pride. A meek and unassuming attitude means that conscious light burns with less intensity, yet with a clear flame. The ego is no longer fixated on self-satisfaction. It now exalts God instead of itself, and no longer views itself as self-sufficient.

Although the ego is now less energetic, it maintains focus on the process and sustains the circular distillation by the addition of a mild heat. The alchemists always said that over-heating the vessel ruins the process. It is imperative to maintain a mild and continuous heat. Some say that the light of the moon is enough. They assert, again and again, that the artifex must maintain a truly pious attitude, otherwise the operation has no chance of success.

What the alchemists had in mind was not first and foremost a process of assimilation, the way in which Jung understands the alchemical

opus. Rather, it denotes a process of

complementation during which the unconscious Self emerges out of the ‘massa confusa’ and takes shape as a complementarian composite of opposites. The process can only take place in mild light, as the strong light of ego consciousness would only transfix the components on its spines. Nor can it go on in total darkness, where the contents would freeze and the process risk coming to a halt. The alchemists believed that the metals slowly mature (into gold, eventually) in the womb of the earth. In the laboratory, an artificial womb is created, which serves to speed up the process (cf. De Pascalis, p.13 & p.94). The symbol of the ‘golden coral growing in the ocean’ also seems to signify an autonomous process (ibid. p.27). What generates the growth is ‘the philosophical fire’, which is a potential fire within the elements themselves that must be activated and fed. Giovanni Pontano says that it is “a fire of modest flame, for it is with a modest fire that the Work may be carried out” (ibid. p.101).

Evidently, the ego must become small and simple, remain virtuous and modest. This attitude corresponds to the standpoint of Christian mystics, such as St John of the Cross, whose teachings Jung rejected out of hand, saying that apophatic mysticism and the ‘via negativa’ “has nothing to do” with individuation. Although Jung, according to my argument, misinterpreted alchemy to a degree, he maintained an attitude of reverence toward the spirit. The unconscious realm was, in a sense, holy to him. He went as far as saying that, to him, the unconscious is God. This attitude is reflected in his dream, when he bows down before the holy Uriah. Of course, this attitude of reverence made him reluctant to “kill” every psychic content by means of assimilation.

Nevertheless, this misinterpretation has taken a turn for the worse in some of his followers. The unchristian attitude of “killing the unconscious” is probably what has given rise to neurotic forms of thought in the psychoanalytic school, too.

The peregrinatio

Jung’s view of the spiritual journey requires a “confrontation

with the unconscious”, as the chapter in his autobiography is named.

It entails a dissolution of the ego in the unconscious sea, wherefrom the ego reemerges

as a better approximation of the Self. The process is close to going through a

schizophrenic episode. It is possible to interpret the

night sea journey,

and the

nigredo in this way, i.e., as the hero’s journey into chaos.

However, I argue that it is better understood as the journey of the

Self,

during which the effects on the ego system are secondary. When the Self goes

through the sufferings of the nigredo, the ego would likely experience “dryness”

and passivity, a condition illustrated in “Psychology and Alchemy” (Jung, 1980, p.275) where an

alchemist meditates in nature. The non-secular person must himself go through

hardship because he must, more or less, stand apart from the social sphere. His

sufferings depend on the circumstances of life. He need not go through a

next to schizophrenic stage, when the ego is dissolved in an overwhelming

experience of the Self. Murray Stein says that Jung’s “Answer to Job” is “tendentious”

in the way Jung deliberately accommodates the divine drama within the

psychological realm:

Answer to Job is tendentious. It is driven to its conclusions by a reading

of history and the development of human consciousness that sees humankind as

having left the mythical and the metaphysical eras behind, and as now having

entered into the psychological. Answer to Job does not stand in the tradition

of theological Biblical criticism and commentary, which answer to a particular

religious tradition on one side and to conventions of historical inquiry and

scholarship on the other. The psyche replaces heaven and hell and all such

metaphysical beings as gods and goddesses, angels and devils, as the field in

which the essential conflicts rage and must be won or lost or worked through.

And with this comes the ethical responsibility for ordinary mortals to take on

the burden of ‘incarnation’. Incarnation for modern men and women means entering