The objective in Chinese Chess (Xiangqi) is to checkmate the opponent's General. It's also a win to stalemate your opponent — this usually only happens when a player is reduced to a lone king. A player may not force a repetition of moves. The horizontal space across the center of the board is the river separating the territories of the two sides. Elephants are not allowed to cross the river, whereas Soldiers promote once they cross it. The 3x3 box marked with an "X" is the General's imperial palace or fortress. Each General and his Mandarins may not leave their fortress. There are seven pieces in Chinese Chess:

Soldier/Pawn (zu/tsut, bing/ping = foot soldier)

Soldiers can move forward until they cross the center section of the board (called "crossing the river") where they gain the ability to move left and right. The Soldiers are initially positioned on the 4th and 7th rank.

Horse/Knight (ma = horse)

Horses move like a Knight in Chess, except that they can't jump over other pieces. They step outward on a row or column, then diagonally outward one step. If something is adjacent to a Horse on a row or column, it can't move in that direction. The Horses are initially positioned on the 2nd and 8th file.

Elephant (xiang/tseung = elephant; xiang/sheung = minister/premier)

Elephants move diagonally two steps. However, Elephants cannot jump over other pieces, so an Elephant is blocked in any direction where another piece is diagonally next to it. Elephants are defensive pieces: they must stay on their side of the board and cannot cross the 'river.' The Elephant is similar (but without the ability to leap) to the Alfil in Shatranj, the precursor to the modern Bishop. The Elephants are initially positioned on the 3rd and 7th file.

Chariot/Rook (ju/kui = chariot)

Chariots move like the Rook in Western Chess, that is, any number of squares along a row or column. The Chariots are initially positioned in the corners.

Cannon (pao = cannon)

Cannons move like Chariots/Rooks, by sliding any number of squares along a row or column, but they can capture an enemy only if there is another piece (of either side) in between. Thus to capture they leap over the intervening piece and land on the enemy piece, like a cannonball. One account of Xiangqi dates the introduction of the cannon at 839 A.D. The Cannons are initially positioned on the 3rd and 8th rank.

Mandarin (shi/see = counsellor)

The Mandarin must stay confined to the fortress, and can only move a single step along the diagonal lines shown. This gives it only 5 possible positions. This piece is often translated into other names such as Assistant, Guard, Counsellor, and Officer. The Mandarins are placed beside the General.

General/King (jiang/cheung = general, shuai/sui = general)

The General is confined to the fortress and can only move a step at a time horizontally or vertically. It also has the special power to threaten an enemy General across the board along an open file. For this reason, it is not permitted to make a move that leaves the two Generals facing each other with nothing in between. The object of the game is to checkmate the opponent's General. The General is positioned in the middle.

Discussion

Chinese Chess, or Xiangqi (Elephant Chess), derives from the same source as Western Chess, though there is much debate over whether the earliest form of chess began in India or China. The first definite reference to the game is from the 8th century; the present form dates from about the beginning of the 12th century. Xiangqi is still a popular folk game in China. Among the Chinese, the rules are said to be universally known, and it is claimed that Xiangqi is the world's most popular game, with perhaps 200 million players.

Unlike Western Chess, having an extra piece is not as important as having a strong attack. Attack on the General can come at any stage of the game. Chariots (Rooks) are the most valuable pieces, being worth almost twice as much as a Cannon. The Horse is less valuable than the Cannon in the opening, but becomes stronger as the game progresses, as it becomes more mobile and the Cannon less so (due to the lack of 'screens'). Mandarins and Elephants are purely defensive pieces. Soldiers are very weak until they cross the river and promote, where their increased mobility makes them useful in attack.

The most common opening moves are: moving either Cannon behind the central Soldier, moving a Horse to defend the central Soldier (this also frees the Chariot to occupy the adjacent file), pushing a c-file or g-file Soldier to give a Horse a path to advance to the river's edge, or bringing either Elephant to the front of the fortress to protect its partner. This program can be used as a Xiangqi opening database. Stored games are double-clickable. The program will then load the last position in the stored game. This is useful if you want to maintain a database. Games can be stored in a directory tree, where names of directories correspond to opening names.

Endgames have been studied even more deeply than in Western chess, and much is known about mating possibilities with various combinations of pieces. A lone General can be mated (remember that checkmate and stalemate both win, and Generals cannot face each other a file with no intervening pieces) by General and Soldier, General and Horse, or General and Chariot. A Chariot can even win against two Elephants or two Mandarins; two Soldiers can defeat a single Elephant or two Mandarins. Many detailed endgame examples are given in H. T. Lau's book “Chinese Chess”. Chinese Chess is more technical than Western Chess, which contains many deep strategical aspects and is more many-sided. On the other hand, unlike Western Chess, Chinese Chess is always stimulating and never becomes tedious.

Literature on the game is plentiful in Chinese (and game transcripts can be understood with a little study, by learning the characters for the pieces, Chinese numbers, and a few miscellaneous characters). English-language sources are less abundant. One example is Games Ancient and Oriental and How to Play Them by Edward Falkener.

In this implementation I have applied tweaking to alter the relative values of the pieces. Although these values will change somewhat during play, the initial values are as follows. I don't know if they are ideal but they clearly improve play. I tested my version against the Zillions version on a 1.6 GHz computer, at 15 sec per move. The colours were alternated and the openings went differently in each game. My version won six games out of six. The Chariot's value is defined as 1.00. Note that the Soldier's value increases at the other side. My guess is that a promoted Soldier is about equal to an Elephant. This program was also tested against the freeware Qianhong and its plugins (ElephantEye, etc.), and it wins seemingly easily. However, it is weaker than XieXie by Pascal Tang.

Piece values

Chariot: 1.00

Cannon: 0.60

Horse: 0.43

Elephant: 0.18

Soldier: 0.18

Mandarin: 0.15

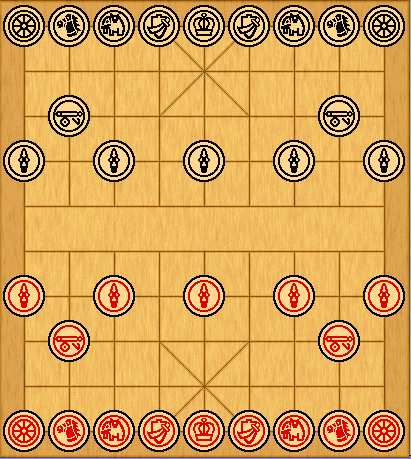

Traditional board

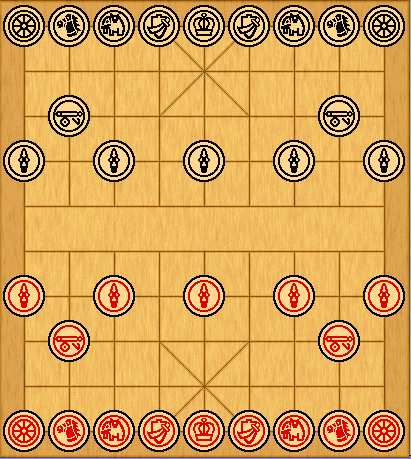

The following image shows the standard pieces

with Chinese signs:

• You can download my free Chinese Chess program here (updated 2012-11-18), but you must own the software Zillions of Games to be able to run it.

• You can play Chinese Chess by e-mail, against a human opponent, here.

• See also Flexible Chinese Chess (F-Xiangqi).

• Don't miss my other chess variants.

© Mats Winther, 2006