“Christ with hand raised in the sign of benediction”. Vä church, Scania, Sweden. (Anonymous painter, first half 12th century.)

Abstract: Depth psychology cannot compensate for the loss of spiritual tradition, nor can God make his abode in the psyche. Today, spiritual symbols are often misinterpreted in psychological terms. To remedy this, psychological theory must be developed to accommodate spiritual transcendence as complementary to psychology’s worldly perspective. The path of worldly withdrawal and spiritual contemplation is equally important as cultural expression and the psychic integration of the unconscious. The article discusses various spiritual traditions and takes a critical look at the Hermetic tradition. The nature of faith is discussed.

Keywords: religiosity, faith, Neoplatonism, Hermeticism, metaphorical unconscious, mysticism, Wasteland, animism, synchronicity, Baining people, Pseudo-Dionysius, Kirpal Singh, Carl Jung, David Tacey.

Introduction

In another article (Winther, 2015, here) I provided an example where the spiritual or metaphysical paradigm is equally viable as the psychological, specifically in questions of morality. Good and evil mustn’t be understood solely in psychological terms. Here I substantiate my view about the psychological misinterpretation of spirit. The latter amounts to an encroachment of the psychological upon the spiritual. According to David Henderson (2014), depth psychology, in a way, represents the modern continuation of negative theology; the via negativa (cf. Tacey, 2014). Tacey says that “[the] Unknowing of apophatic theology becomes the ‘unconscious’ of depth psychology”. It follows that the Deus absconditus (hidden God) now takes his abode in the psychoid unconscious (cf. Jung, 1977, pars. 786-89). Jung says:

[It] is the decisive factors in the unconscious psyche, the archetypes, which constitute the structure of the collective unconscious. The latter represents a psyche that is identical in all individuals. It cannot be directly perceived or “represented,” in contrast to the perceptible psychic phenomena, and on account of its “irrepresentable” nature I have called it “psychoid.” (Jung, 1978, par. 840)

This coincides with the Kantian distinction between phenomenon and noumenon, where the latter term corresponds to the psychoid. On this view, the unconscious extends beyond the properly psychic into a realm which cannot, per definition, be integrated with consciousness. It is not un-conscious anymore, that is, deficiently conscious. Rather, it is the Unknown in the sense of the Kantian noumenon. Kant was the first to conceive of a noumenal world which is completely unknowable to humans. It is related to Kant’s thing-in-itself, a consequence of his deductive philosophy. It means that underlying the perceptible is a world that forever remains beyond the bounds of human awareness. It has generally been regarded an awkward by-product of his ‘transcendental deduction’.

Such a noumenal notion was completely foreign to the school of negative theology, which includes luminaries such as Proclus, Pseudo-Dionysius, the anonymous author of Cloud of Unknowing, and St John of the Cross. The unknowability of God appertains to the fact that God cannot be entirely known either through thought or sense. But this does not mean that God is forever beyond reach. On the contrary, God is wholly discoverable; but it requires a process of unknowing during which we shed every concept derived from finite being. In a centering form of contemplation the soul turns inward from the multiplicity of external things. Thus, the God of Unknowing, as a concept, refers to the fact that he is known through a process of unknowing, not that he is inaccessible. In the mystical union (unio mystica) the contemplative attains knowledge of God so profound that it eclipses any knowledge of external things; so He is anything but a noumenon.

By love may He be gotten and holden; but by thought never. And therefore, although it be good sometime to think of the kindness and the worthiness of God in special, and although it be a light and a part of contemplation: nevertheless yet in this work it shall be cast down and covered with a cloud of forgetting. And thou shalt step above it stalwartly, but Mistily, with a devout and a pleasing stirring of love, and try for to pierce that darkness above thee. And smite upon that thick cloud of unknowing with a sharp dart of longing love; and go not thence for thing that befalleth. (The Cloud of Unknowing, 1922)

Thus, the predication of a psychic realm that, on principle, cannot be known is a misrepresentation of negative theology. It cannot be said to represent the modern continuation of negative theology, for the Deus absconditus is merely hidden and not transcendental in the absolute sense. In theology, the transcendence of God has never been regarded a transcendence in the sense of a truly radical alterity. In the religions of the world, as well as spiritual tradition, the spiritual and the worldly constitute two different worlds only from the standpoint of human perception. As God is (at least partly) super-natural, we can slough off the natural and join him. Yet, the archetype-as-such, per definition, remains forever beyond the bounds of consciousness, as a form of transcendental meaning. Thus, like the Kantian thing-in-itself, it cannot at any time be detected, not even by a scientific apparatus, since it is otherworldly in the absolute sense. Relative transcendence, on the other hand, as postulated by negative theology, is perfectly feasible. Thanks to science, we are today able to detect beautiful ultraviolet patterns on flowers which have always transcended our awareness.

The notion of absolute transcendence, in the Kantian and Jungian sense, causes consternation in the heads of philosophers. It seems to necessitate an illogical and one-sided bond between the conscious mind and noumenal reality. When consciousness and science encroaches upon the unknown, the noumenal always draws back into obscurity, escaping attention. So it behaves like the squirrel in the woods, who always places himself at the opposite side of the tree as the wanderer passes by.

Although it is conceivable that a self-conscious God should behave in such an eccentric way, it remains inexplicable as a function of archetypal reality. The noumenal, however, is capable of reaching into our world, surreptitiously and inexplicably governing the universe. Such a God can see us, but we can never see him. It is a one-sided relation, as we cannot reach out in the other direction. In metaphysical terms, there is an absolute border in one direction, but not in the other. We could equally well postulate the existence of an elephant in the room, or a transcendental giraffe, forever beyond the bounds of experience. It is fantasy, but neither theology nor philosophy proper. It is evident from the following excerpt that Jung, in the following of Kant and Schopenhauer, is a proponent of transcendental idealism.

[It would be wiser] to make an unknown psychic or perhaps psychoid factor in the human realm responsible for inspirations and suchlike happenings […] It presents a world of relatively autonomous “images,” including the manifold God-images, which whenever they appear are called “God” by naïve people and, because of their numinosity (the equivalent of autonomy!), are taken to be such […]

The realization might by this time be dawning that when we talk of God or gods we are speaking of debatable images from the psychoid realm. The existence of a transcendental reality is indeed evident in itself, but it is uncommonly difficult for our consciousness to construct intellectual models which would give a graphic description of the reality we have perceived. Our hypotheses are uncertain and groping, and nothing offers us the assurance that they may ultimately prove correct. That the world inside and outside ourselves rests on a transcendental background is as certain as our own existence, but it is equally certain that the direct perception of the archetypal world inside us is just as doubtfully correct as that of the physical world outside us. If we are convinced that we know the ultimate truth concerning metaphysical things, this means nothing more than the archetypal images have taken possession of our powers of thought and feeling, so that they lose their quality as functions at our disposal […]

In view of this extremely uncertain situation it seems to me very much more cautious and reasonable to take cognizance of the fact that there is not only a psychic but also a psychoid unconscious, before presuming to pronounce metaphysical judgements which are incommensurable with human reason […]

That a psychological approach to these matters draws man more into the centre of the picture as the measure of all things cannot be denied. But this gives him a significance which is not without justification. (Jung, CW 14, pars. 786-89)

Jung’s philosophy is transcendental idealism with a bent toward the fantastic. Kant argues that human beings have no way of apprehending noumenal properties. We can think of noumena only under the precept of an unknown something. Reason remains limited to what it perceives, making many questions of traditional metaphysics unanswerable by reason (cf. Wiki, ‘noumenon’). It calls to mind Wittgenstein’s proposition: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent” (arguably his sole valuable contribution to philosophy, after which he took a vow of silence in philosophical matters). Schopenhauer, however, identifies the noumenon as the universal Will. Jung continues along these lines and endows the noumenon with divine properties; the unus mundus as common ground for psyche and matter, synchronicity as the coincidence of psychic meaning and material event, and archetype as transcendental meaning (reminiscent of Kant’s ideas of reason, remote from Plato’s notion). Jung argues that old-fangled metaphysical concepts, such as the Almighty God, are naïve and incommensurable with human reason, and that’s why he has found out new concepts, commensurable with reason. These, however, due to their noumenal nature, can never be verified by science. We can only make inferential conjectures. However, many would prefer the word misconstrual. ‘Coincidences’ lend themselves finely to misconstrual as synchronistic meaningful events (cf. Winther, 2012, here).

On the other hand, should psychology redefine the spirit as resident wholly within the psyche, then it amounts to psychologization, since it allows for the integration with consciousness. In epistemological terms, it is equally incongruous with negative theology, as the latter says that the spirit transcends our worldly categories. Thus, in order to appropriate the spiritual tradition, Jung saw it necessary to define another form of psyche; the realm of the psychoid, corresponding to Kantian noumenal reality. But this didn’t work either.

The conclusion is that the (semi-)psychologization of spiritual tradition amounts to a misrepresentation of the same. The rationale is that it shall allow the reinterpretation of spiritual symbols in psychological terms. In reality, it leads to a misinterpretation of spirit. To stand aside from worldly multiplicity is to no avail, as the noumenal (the psychoid) remains ever unattainable. It changes everything. Psychic integration and cultural expression become the only paths forward.

The psychological paradigm

Carl Jung brought the psyche centre stage and gave preference to the motto ‘esse in anima’ before the two traditional metaphysical mottos, ‘esse in spiritu’ and ‘esse in re’. As a consequence, many spiritual symbols have become reinterpreted in psychological terms. For example, he takes alchemy’s scintillae (divine sparks present in matter) to mean the unconscious as multiple consciousnesses (cf. Jung, 1978, par. 388). The misinterpretation of spirit is a deleterious consequence of the Jungian focus on psychic integration. Even so, Jung sees religion as a partially adequate therapeutical system and gives consent to religion as a venerable institution, well suited for the people that have not yet progressed to a psychological consciousness. His disciple Edward F. Edinger has, however, taken psychological misinterpretation to new levels (cf. Winther, 1999, here). To rectify the lopsidedness the psychological paradigm must be complemented with a spiritual.

In the book The Darkening Spirit, David Tacey accounts for the problems surrounding religion and its unruly cousin, namely spirituality. The phenomenon of spirit is portrayed as the undercurrent of culture, religion, and civilization. As a consequence of routinization, the spirit will sooner or later vacate the symbols and plunge into profaneness. Conscious cultural and religious symbols become barren, void of meaning for the present generation.

Tacey connects this view of spirit (i.e., as emerging from “below” or from a barren Wasteland) with the alchemical symbology. However, I think it also reflects upon the scientific view of energy as underlying all the material phenomena. Energy is typically perceived as the simple and primitive propellant of the beautiful cosmos. It’s like gasoline. Says Tacey: “No content is more undifferentiated or ‘inferior’ than spirit in secular times” (Tacey, 2013, loc. 1991). Of course, such a view of spirit collides with the religious, such as the Neoplatonic, where spirit unfolds from “above”. Its material and cultural manifestations are viewed as vague reflections of a higher spiritual reality.

Evidently, spirit has become psychologized as unconscious libido. To such a degree it has been warped into something else, as it is not really referring to the non-material side of existence anymore. Yet, to make a psychological interpretation of spirit is quite in order, as long as we remember that there is a traditional definition that has its own raison d’être.

In a Jungian understanding, spirit has sunk into the wasteland of the unconscious from where it must be retrieved. Thus, it may rise again to a new formula of religious and cultural expression, allowing people a meaningful outer life. Says Jung: “Only an unparalleled impoverishment of symbolism could enable us to rediscover the gods as psychic factors, that is, as archetypes of the unconscious” (Jung, 1981, par. 50).

Tacey quotes Jung to the effect that we wouldn’t even have an unconscious as long as the psyche is “outside” in the form of art, culture, and religion. As long as societal institutions provide a consummate and modern formulation of the spirit, its symbols will speak directly to the soul and encourage it to its full expression. Tacey says:

The modern condition and the discipline of psychology is a mixed blessing, and a poor consolation for what might otherwise be a vibrant and rich cultural order. A society that discovers the indwelling psyche is a society that is poor in spirit. Depth psychology is thus a ‘consolation prize’ in an otherwise gloomy and featureless landscape. (Tacey, 2013, loc. 497-9).

The argument is dubious due to the fact that such a spirited culture has never existed; nor will it ever come to be. It is the good old myth of the Golden Age; the first Age of Man. Also in the time of Socrates and Plato, society was replete with relativism and atheism, something which motivated Plato to undertake his enormous work. Before the Greek era, civilization didn’t even exist in Europe. We have to go back to the hunter-gatherers to find a time in which spiritual beings took their abode in the surroundings. Yet, those times were anything but idyllic. Anthropologists have found that also hunter-gatherers entertain the myth of a Golden Age akin to a generous motherly paradise.

As Tacey shows, Jung has brought to life certain Neo-Pagan ideas, such as the ‘anima mundi’, which shall serve to imbue the world with meaning, leading to a “resacralization of the world”. Thus, he incited a regression that came into full bloom in James Hillman’s Archetypal Psychology. On this view, the archetypal reality of the unconscious doesn’t count for much. It is the outer world, with its diverse cultural manifestations of reified spirit, which takes precedence as the “higher reality”. So the archetype is a mere form lacking in value as long as it cannot find expression in societal life.

This turns the Platonic standpoint on its head. There is no longer a quest to climb out of Plato’s cave into the daylight of the spiritual Forms. Instead, the movement goes in the other direction. The path of psychological redemption equates to the refinement of diverse cultural expressions derived from inconspicuous archetypes found in the putrid mud of the unconscious. Accordingly, we shall remain in the deep recesses of the worldly cave, produce culture, and paint the walls therein.

Synchronicity

The concept of synchronicity was invented by Jung to imbue the world with meaning, since it connects the inner with the outer. But is it really a new concept? Jean Piaget (1975) has investigated animistic thinking in children. He relates:

A little girl was out for a walk with her mother one very windy day. The buffeting of the wind delighted her at first, but she soon grew tired of it: ‘Wind make Mamma’s hair untidy; Babba (her name) make Mamma’s hair tidy, so wind not blow again.’ Three weeks later the child was out of doors in the rain; she said to her mother: ‘Mamma, dry Babba’s hands, so not rain any more.’ (Piaget, 1975, p. 148)

This thinking follows a similar animistic pattern as Richard Wilhelm’s account of the rainmaker (cf. Jung, 1977, pp. 419-20:note). An old man was brought to a part of China that suffered from drought, something which caused unrest in society. Naturally, he sat down and collected himself for three days, since he wanted to regain harmony. After three days he was back in Tao and then a snow storm arrived.

The rainmaker is like a father figure who succeeds in regaining inner harmony. Thus, both society and weather system are bound to regain harmony, too. It is similar to the thinking produced by the little girl. Although people in aboriginal cultures are wholly capable of logical thought, they have retained certain prelogical concepts of childhood. Childhood animism, unlike adult logical thought, is archaic and original, and so it must have its origin in the divine. When science is helpless, we have a tendency to fall back on archaic thought.

The shamanic ritual has a therapeutic effect in that it serves to mollify a growing unrest in society. But no other effect is produced since there is no coincidence between mental events and physical. Science can produce rain by launching rockets containing silver-iodide, but rainmakers can’t. Still, Jung regurgitates the notion, renames it synchronicity, and claims that the rainmaker story is an example thereof. It belongs in his project of reanimating the world — to paint Plato’s cave in beautiful colours, so to speak. Yet synchronicity adds nothing new, because every child thinks like that and animistic thoughtways are part and parcel of aboriginal culture.

Nature is like an open book where it’s possible to read between the lines. Arguably, when “meaningful events” occur, they are better regarded as messages from God rather than effects of a natural law. The extent to which they are taken seriously depends on the nature of the subject’s religiosity and the personal quality of the God-relation.

The Wasteland

According to a Jungian view, we live today in a gloomy wasteland that needs to be reanimated. It is a curious concept. After all, culture has never been so rich and multifaceted. A more appropriate image is perhaps that we live in a vast and abundant grocery store where some people (not all) can’t seem to find anything to eat. At least, many are dissatisfied with the abundant wealth of food products. Comparatively, in Roman times an artist would often find the lack of pigments frustrating. An intellectual would suffer from the scarcity of literature. Today, I can simply push a button and listen to J. S. Bach. There is an enormous wealth of cultural products. Above all, it is today much easier to find creative expression in art, music, intellectual development, etc. In fact, the computer is today used for all these purposes. I can also play online chess with people all over the world.

Despite this enormous wealth of cultural expression and creative opportunity there is spiritual frustration in the population, due to a lack of deeper meaning. Just as in Plato’s times, people have a longing for God. This leads me to the conclusion that culture cannot satisfy our inner need. When the psychological path of culture is fulfilled, we must turn in the other direction and commence the journey out of Plato’s cave (The Republic, 514a-520a).

A full-fledged culture, where the human soul is wholly externalized, is a Utopian concept that has its roots in Romantic and Hegelian philosophy. Although it is commonly associated with post-Jungian theory, Tacey shows that Jung himself has initiated the development toward Neo-Paganism. Tacey, however, denotes it a ‘spirituality of wholeness’ or a ‘spirituality of embodiment’. ‘Creation spirituality’ attempts to regard body, matter and nature, as holy (cf. Tacey, 2013, loc. 2128-29).

Yet it flies in the face of the many time-honoured spiritual teachings of the world, as taught by Buddha, Jesus, Plato, Plotinus, et al. This is not a little problem. Jung repudiates the old spiritual ideal of ‘perfection’ and wants to put ‘wholeness’ in its stead. Says Tacey:

The newly emerging spirituality emphasises a wholeness of body, psyche and spirit. In the previous age, spirit appeared to seek an upward movement toward the sublime, the holy. It wanted to shrug off nature, instinct, body and sexuality, and being ‘spiritual’ meant striving for ‘perfection’ […]

We are urged to seek a new way of connecting with the divine, a way to the unification of body, psyche, spirit. As the spirit is released from its unconscious state, it does not move heavenward but stays with and on the earth, serving to bind together the things that were formerly torn apart. (ibid. loc. 1978-87)

In Jung’s late thought, the ideal outcome of individual psychic integration and its collective counterpart (cultural expression) is that the unconscious becomes like an extinct volcano. Vanquished and defunct, it leaves us with the psychoid metaphysical sphere as a token of mystery. This is transcendental philosophy with a Hegelian bent, uncorroborated by science. Anthropological research about the aboriginal Baining society calls into question the notion of cultural realization as a necessary expression of the psychic form of spirit.

During the 1970s, and again in the early 1990s, anthropologist Jane Fajans studied the Baining people of Papua New Guinea (Fajans, 1997). Their culture is very meagre as they lack myths, religious traditions, and puberty rites. It is a society without institutions, aside from the nuclear family. So there are no shamans, gods, kings, doctors, etc. On account of their colourless life, they have by earlier anthropologists been regarded as “boring” to the point of despair, and virtually unstudiable.

Fajans explains that they eschew everything ‘natural’ and instead value activities and products associated with work. Work revolves around mundane things, such as food production. The Baining say, “We are human because we work”. Natural drives and desires are associated with shame. Sexuality, since it is natural, is being downplayed. It is better to adopt a child, as it is less natural than to raise one’s own. They devalue play among children and teach them to be productive instead. A hundred years ago the Baining were cannibals, but they have been missionized and children now go to school. Nevertheless, the Baining rarely abandon the old ways and society is remarkably resilient. They are exceedingly puritanical.

High culture and religion is not only what defines civilization — in fact, it also sustains advanced civilization. In aboriginal societies, however, it seems that ‘culture’ is an optional appendix. How does this square with Jungian theory? Allegedly, if a society suffers from an impoverishment of symbolism it must cause a rebound of the dark unconscious in the form of societal havoc, neurosis, and addiction. The standpoint is here related by Tacey:

In stable cultures, [Jung] argues, the archetypes are at rest, safely invested in the non-rational forms of ritual, art and culture. But when ignored by modernity they become devastatingly active. Spirit, which is the expression of what is best and highest in humanity, becomes our adversary. ‘What is suppressed comes up again in another place in altered form, but this time loaded with resentment that makes the otherwise natural impulse our enemy.’ Primal forces are disturbed and have been ‘washed to the surface’ by our negligence of the symbolic order. This is, in effect, the psychological equivalent of saying vengeance has been wreaked upon us by neglected and savage gods. (Tacey, 2013, loc. 465-71)

From a psychological perspective, the Baining is the most secularized society imaginable. They have no notion of dei loci, i.e., spirits that dwell among trees and wellsprings. Yet, it is a stable culture with apparently harmonious citizens. In this example we cannot find support for the Hegelian notion that spirit is equal to established culture. Nor does neoteric spirit manifest in the way of unconscious archetypes searching for expression, seeing that this development does not take place.

Arguably, spirit belongs to a different paradigm than the psychic and symbolic unconscious. On this view, the Baining is not a ‘psychological tribe’. Rather, it is a ‘spiritual tribe’, akin to a Puritan community of 17th century New England, or a medieval community of monks, occupied with simple labour and fixed on restraining their natural desires. A society may remain “flat and dull”, void of cultural and religious creativity, if and only if the members turn to the spirit. If it weren’t for this, Jung’s analysis is bound to hold true. It’s just that there exists an alternative path of spirit proper, which is different than ‘completeness’ in the manner of instinctual refinement and cultural expression in aesthetic and religious form. It means to devote one’s life to God in the way of a sacrifice. The devotee relinquishes worldly passions, including the goal of self-fulfilment, and instead surrenders the vital power of consciousness for the intensification of the spirit. I have suggested a psychological term for this, namely ‘complementation’ (cf. Winther, 2014, here). This also entails the opening of the ‘inner eye’.

The spiritual paradigm

The Baining phenomenon cannot be accounted for by Jungian psychology. This does not mean that the Jungian standpoint as explicated by Tacey is wrong. It only means that it is inadequate as a theory of reality as a whole. The theory is monistic in the sense that it accounts for all phenomena in terms of psychology. Yet, the spiritual (trinitarian) paradigm, which is psychology’s complementary opposite, must be accepted as a viable worldview. Otherwise psychology is bound to misinterpret or negate the teachings of its counterpole. Tacey says:

[Spirituality] has been radically redefined for a new era. It operates in a world-affirming manner, and serves the integration of body, psyche and spirit. Spirituality has become ‘darker’ and more chthonic, and is ‘burdened’ or constrained by the Self. It is subject to a new authority, one greater than the church or any established social authority […]

The confused theologians had come with traditional expectations that those ‘called’ to spirituality would need to sacrifice certain ‘worldly’ things, including the pleasures of the flesh. But in advocating ‘spirituality’, contemporary folk are not saying they want to become devout or pious. If they have wholeness on their minds, they realise this must include the body, sexuality, the instincts, drives and ‘baser’ elements of personality […]

The image of the divine emerging in contemporary discourses is far removed from the traditional notion of a punishing God who strives toward perfection. (Tacey, 2013, loc. 2049-63)

Yet the trinitarian paradigm has its own raison d’être. It is not wrong to strive after perfection, despite the fact that such a notion is irreconcilable with psychology. This is equally paradoxical as the complementarity of quantum phenomena. Still, it is the facts of reality. It also explains why there is a continual conflict between spirit and the diverse expressions of culture and religion. When people become absorbed in the manifold expressions of culture, it may deflect them from the spirit. This has been a long-standing argument among spiritual teachers who have not only advocated the curtailment of natural drives, but also the reduction of musical, artistic, and religious expression. Nonetheless, a minimum of cultural expression could serve to bolster the spirit. The Baining seem to uphold this view, since they condone a form of stylized dance that lacks symbolic meaning. Monks have their Gregorian chant.

Kirpal Singh (satguru, 1894-1974) has a different take on the coming spiritual revolution (1997) to which end he recommends a change in education. It must also be spiritually oriented and not merely centered on passing examinations, getting certificates and diplomas, and seeking employment (cf. p. 273). Neither politics nor religion can heal the rifts in the world. What all religions and people have in common, however, is the spirit within: “[God] is one, though there may be many outer ways of worship, you see; but the ultimate, the inner Way, is the same for all” (p. 3).

Since spirit is the source of all religion it functions as a unifying factor should people resolve to find the source: “If you have love for God, and God resides in every heart, and we are of the same essence as that of God, then naturally we will have love for all and have no hatred” (p. 204). Since Singh is rooted in Indian culture, he puts emphasis on guruship. To have success on the spiritual path it is necessary to meet some guru: “Without the Master we cannot reach the Lord — it has never been possible, nor ever will be” (p. 98). Yet he also has a notion that the guru power is within: “Master is within me” (p. 35). Singh says:

How can you rise above body-consciousness? If you can rise above it by your own efforts, you are welcome to do it. If you cannot, you can seek the help of someone who goes up and has the competency to raise your soul, to liberate your soul, from the clutches of mind and the outgoing faculties, someone who is able to give you an experience of opening the inner eye to see the Light of God and opening the inner ear to hear the Voice of God. Call him by any name you like. (Singh, 1997, p. 197)

There is a sense of rivalry between spiritual tradition and religion. Singh says about religion:

When we take the first step of joining any religion, we go to churches and to the holy places of worship where the ministers of those churches tell us to repeat the scriptures from day to day. They give us the same story: there is God; there is Son of God; you can meet Him through the Son of man; God is within you: “The Kingdom of God is within you.” These teachings are only meant to develop love and devotion within us to know God. By hearing them, a strong desire to know God is developed. And then, those who by reading scriptures and hearing daily lectures have gained that strong desire in them to see God, say, “O ministers, stop all the reading of these scriptures to me now. Tell me how to see Him. The wish to know God has been developed in me; that’s an earnest desire. I don’t like your preachings anymore; now tell me how to know God, how to see God. All through life we’ve been hearing these long yarns: ‘God is there; God is within you. You have joined this religion; remain in this religion.’ O minister, what are you doing? You are after keeping your formations intact; no one should leave them. And I am after finding God. Religions have to do with my body. If He is within me and beyond all senses, then tell me how to know Him, how to see Him.” That’s the earnest desire of any lover of God […]

Religions only promise experience of God after death, not in life. But mysticism promises it in life — and Masters — never after death. If you want to live on credit, it is your own choice. For everything in the world you want cash. If, in the case of this life-and-death problem, you would like to wait till after death, it is up to you. (Singh, 1997, p. 61)

The well-known motto “Gnothi seauton” (Know thyself) does not allude to the modern psychological precept, i.e., to carry out the integration of the unconscious. Rather, it means that we must get closer to our spiritual inner being. To be near the realized spirit inside is to be near God, since only like can know like. In traditional spirituality, it requires that one rises above body-consciousness by shedding worldly attachments, as explicated in these three excerpts:

Burn away all your outer attachments; burn them away, and from their ashes make ink, and with your conscious Self go on writing the praises of God. As long as we are attached outside, we cannot know ourselves; when we know ourselves with our conscious Self we can see what He is. (ibid. p. 4)

[Your] attention is diffused into the world and identified with it. You are awakened outside and are asleep from within. The God-Power is already within you, waiting for you. Your true home is the True Home of your Father, that is, of all-consciousness and all wisdom. Why are you stuck fast in this material world, in the outside things? (ibid. p. 25)

Now, the question arises: Why can’t we see Him? When the Masters say that they do see Him, why can’t we see Him? They say, Because He is the subtlest of the subtlest: Alakh, Agam. Try to understand by an example. The air appears to be all vacant — nothing there; but if you look at it through a microscope, what happens? What you see is magnified seven hundred times, and then you find that the atmosphere is full of microbes. So if our eye becomes as subtle as He is, or if He becomes as gross as we are, we will be able to see Him. (ibid. p. 9)

Pseudo-Dionysius

Dionysius the Areopagite is the pseudonym of an enormously influential Christian Neoplatonic theologian and mystic of the late 5th and early 6th centuries. He took his name from the biblical figure St Dionysius the Areopagite (Acts 17:34). Today, he is often referred to as Pseudo-Dionysius. His approach to God is twofold; the affirmative and the negative — the kataphatic and the apophatic. Fran O’Rourke says:

Dionysius explicitly recognises indeed two distinct approaches within the tradition of theology itself: the one silent and mystical, the other open and manifest; the former mode is symbolic and presupposes a mystic initiation: the latter is philosophic and demonstrative. Dionysius notes, however, that the two traditions intertwine: the ineffable with the manifest. Some truths about God, he states elsewhere, are unfolded ‘according to true reason’ […], others ‘in a manner beyond our rational power as mysteries according to divine transmission.’ (O’Rourke, 1992, pp. 5-6)

Thus, things and creatures of the world are “emissaries of the divine silence” — lights that shine in witness to the hidden God:

The world of finite beings revealed in our experience was created by God and may, therefore, be taken as a symbol of the divine. The spiritual is cloaked in the sensible, the supra-ontological with that which has being. In creation God has established throughout the universe multiple images of his infinite perfection, fashioning a tapestry […] of separate symbols to unfold his simplicity, covering in form and shape what is formless and without shape […]

The visible world has for Dionysius, therefore, a twofold character. The realities of the world at once reveal and conceal the divine. They are an image of God, yet shroud his true nature; they are a help and a hindrance. (ibid. pp. 10-11)

Still, it is evident that he attaches greater significance to the path of negative knowledge. After all, the worldly, due to its great allure, may cause us to stray from the purposes of God. Dionysius prays, therefore, that “we may come unto this Darkness which is beyond light, and, without seeing and without knowing, to see and to know that which is above vision and knowledge through the realization that by not-seeing and by unknowing we attain to true vision and knowledge…” (Pseudo-Dionysius, 1923, ch. 2). The mystic, “through the inactivity of all his reasoning powers is united by his highest faculty to Him who is wholly unknowable; thus by knowing nothing he knows That which is beyond his knowledge” (ibid. ch. 1). Going beyond intellect is like being enveloped by a deep and silent darkness. Yet this darkness is none other than a floodlight of intelligibility. St Thomas Aquinas says:

[God] is in Himself supremely knowable. But what is supremely knowable in itself, may not be knowable to a particular intellect, on account of the excess of the intelligible object above the intellect; as, for example, the sun, which is supremely visible, cannot be seen by the bat by reason of its excess of light […]

He exists above all that exists; inasmuch as He is His own existence. Hence it does not follow that He cannot be known at all, but that He exceeds every kind of knowledge; which means that He is not comprehended. (The Summa Theologica, I.12.1).

Thus, we fashion our knowledge of God according to our cognitive

capacity. For the purpose of worldly separation, and for to ascend from the particular to the universal, Dionysius saw it necessary to distinguish the negative method of abstraction from the positive method of affirmation (cf. Pseudo-Dionysius, 1923, ch. 2). And so the apophatic part of his theology becomes perhaps excessively negative, something which St Thomas Aquinas succeeded in correcting (cf. O’Rourke, 1992, pp. 95ff). Christian mysticism, in the following of Pseudo-Dionysius, was given to excesses of ascetic practice.

Yet, in my view, the two paths are not far apart but are mutually sustaining. As modern man has cast off much of his former naïveté, worldly misconception and allurement have not the same power over his soul as in antique and medieval times.

Indeed, worldly things, and inner images of mind, are simultaneously revealing and veiling. But unlike ever before, we possess the capacity to unveil creation, making known the lights that shine within. Paradoxically, since the objective mindset of modern man brings with it a critical distancing from the worldly object, it is easier for us to see the reflections of spirit in the world, provided that we temper our worldly ambitions and appetites. The call for a simple life is still valid, but austere asceticism is outmoded.

The problem with modern man is, rather, that he seems at ease only with what he can dominate and calculate. He balks before a truth so wonderful and sublime as an eternal spirit, infinite in being, whose nature is simply to be, and to allow its being to continually overflow into this marvelous universe with its multitude of shapes (cf. O’Rourke, p. 60). The alternative to this mystery is the pedestrian view that the world of mundane experience is in need of nothing beyond itself. In truth, Mother Nature is suffering, and worldly existence is obviously deficient. No wonder, then, that so many fall to alcoholism and substance abuse, and all kinds of madness. The alcoholic has at least made the realization that something is missing, and that’s why he drinks “spirits”. To put man in the centre of the picture, as the measure of all things, is hubristic. It is the recipe for boredom, frustration, and neuroticism, precipitating destructive consequences at the societal level. The one-sided call to integrate the unconscious, for the purpose of personal development and cultural expression, is indeed characteristic of modernity, for it is all about domination and control.

The heavenly tree

The notion of an earthly spirituality of wholeness is supposed to derive from alchemy — Jung’s foremost research subject. Yet the alchemists insisted that perfection in the sense of piousness and simplicity is essential for the success of the process. Nor did it ever occur to them that the spirit Mercurius is an antidote for trinitarian religion.

Jung’s treatment of alchemy amounts to a misinterpretation of spirit. He reinterprets it in terms of psychic individuation to achieve wholeness in the worldly sense — a kind of proto-psychology. It should be noted, however, that he generally treads carefully among the symbols and his study of alchemy has been of benefit. Edward F. Edinger, for his part, translates religious and alchemical images to simplistic psychological theory, always revolving around conscious expansion (cf. Winther, 1999, here).

Jung has a point in so far as alchemy contains many symbols of great psychological value. Nevertheless, it really belongs in the Hermetic tradition according to which the spiritual journey signifies the return to a state of unity with the Divine. It is really about the mystery of spirit, which means that alchemy has continued in the footsteps of Buddha, Jesus, Plato, and Plotinus. The ‘lapis’ is a seemingly insignificant stone which harbours the mercurial spirit. It grows into the incorruptible ‘arbor philosophica’. In like manner, Jesus says about the Kingdom of Heaven that it is “like a grain of mustard seed, which a man took, and put in his own garden. It grew, and became a large tree, and the birds of the sky lodged in its branches” (Luke 13:18-19).

It is a remarkable reversal of religious imagery. After all, the Kingdom of Heaven is no longer viewed as a place with alabaster gates and angels with trumpets. Rather, it is like a mustard seed buried in the earth — a symbol later appropriated by the alchemists. Thus, spirit is being divorced from culture and religion. Jung understands the ‘materia prima’ as the earth of the unconscious out of which the archetypal tree grows. He saw the alchemical opus as a work of integration during which the unconscious archetypes are assimilated in consciousness and come to expression in culture.

In fact, the heavenly tree does not mature in the realm of consciousness. Rather, The Kingdom of Heaven represents spiritual unfoldment, which means that it is mostly an unconscious or semi-conscious process. Since it is truly a spiritual kingdom, its growth does not take place in the conscious realm of culture. Many a theologian would prefer to see the mustard tree as the church and the Christian community, but this is an erroneous concept on a par with Jung’s.

The idea of an unfoldment that takes place entirely in the spirit is central to Neoplatonism, Gnosticism, and Kabbalah. In Kabbalah there is a tree called Sephirot. It represents the divine plan as it unfolds itself in the spiritual universe. It was only a calamity (the breaking of the sephirotic vessels) that gave rise to the material universe.

Neoplatonism begins with the spiritual One, which is utterly simple yet capable of producing the Nous — the first emanation. The One is the seed that unfolds in the noetic realm and concomitant platonic Forms. Only in the last stage of emanation matter emerges. So the birds landing in Jesus’s heavenly tree are to be regarded as spirits — they are spiritual Forms, not cultural products. The growth of the tree represents spiritual unfoldment, not worldly.

In Gnostic and Kabbalistic cosmogony the unfoldment took place before the creation of the world. In Neoplatonism, it is continuous, but mostly predates man. Such metaphysical edifices lend themselves to a religious worldview. Yet, in Jesus’s message, and in the alchemists’, the growth of the heavenly kingdom takes place in the here and now. It makes it a truly spiritual message since it involves the individual. Jesus’s message wasn’t clearly defined in religious terms, and that’s why it took such diverse expression in the first centuries.

Anyway, central to all these conceptions is the individual’s ascension to the Forms. The dwellers in Plato’s cave must avert their gaze from the shadows on the wall and start climbing towards the light. It is a spiritual message: we must avoid fixation on the natural fabrications of consciousness including its cultural and religious forms. Redemption lies not in any form of worldliness.

Jesus and John the Baptist would preach “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand”. But “repent” should really be “turn around”; the accurate rendering of the Greek ‘metanoeite’. In the Swedish bible it is accurately translated as “omvänd eder” (turn yourself around). The message is not directed at sinners in the common sense of the word. Rather, Jesus strikes a blow against religion itself, as well as its many cultural aspects. Accordingly, he broke the Sabbath and dined with sinners. He emphasized instead the spiritual kernel of religion and culture, equal to the Forms that underlie creation. The dwellers in Plato’s cave have the same priority — they turn around and start moving towards the spiritual light. In the Platonic tradition, however, there are two competing schools. One puts emphasis on worldly withdrawal and ascent while the other sees the worldly things as suitable objects for contemplation. After all, the world has been shaped according to the Forms, albeit imperfectly. The latter school seems to find support in Plato himself. It has much to recommend itself, as long as the seeker isn’t caught up in labyrinthine Hermeticism and practical alchemy.

Psychological misinterpretation

Unfortunately, Plato’s allegory of the cave lends itself to psychological misinterpretation. It could be seen as a movement out of unconsciousness into the daylight of worldly and scientific consciousness. Spiritual teachings, including alchemy, tend to be misconstrued in this way. In truth, the light in which the Forms reside is another form of light — the spiritual daylight. Although psychology has proved effective in healing the soul, it is unable to provide sufficient guidance in life. It is time to realize that the paradigm of spirit is equally important as the paradigm of psychology and that they are complementary to each other.

Jesus says, “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven” (Matt 5:3). Those who are not enjoined in the culture and religion of their times are blessed, for they will find the spiritual source. Neither John the Baptist nor Jesus took part in the Pharisaic religion of their times. They were outsiders. Those who wander in darkness without the guidance of institutions are deprived of spirit, which causes them to thirst after spirit. Comparatively, those who live according to the rule, pursuant to a societal career, seldom suffer from thirst, for they receive nourishment from another source than the spirit proper. As a consequence, they lack the capacity to perceive the faint fragrances of spirit. The supramundane source is unobtainable for those who never venture into the Wasteland.

The Wasteland must be understood in those terms, i.e., as the withdrawal from engagement in conscious life. Accordingly, John the Baptist chose to live in the desert. There is no life-fulfilling worldly Kingdom for the people of the spirit. It is in the Wasteland that the Holy Grail must be sought. Jung, however, rejected the spiritual paradigm and sought to explain everything in terms of psychology. That’s why he had dreams of a compensating nature which emphasized instead the spiritual quest. In a dream he visits the barren Grail island (Jung, 1989, pp. 280-82). On its naked rock stood a lonely little house that harboured the Grail. In another dream he visited sooty, dark and rainy, Liverpool. There he finds, in the middle of a small island, a single tree, a magnolia, in a shower of reddish blossoms. There was darkness all around, but the little island blazed with sunlight (ibid. p. 198). It is the same tree that Jesus was talking about, equal to the ‘arbor philosophica’ of the alchemists. It grows in the Wasteland. It is not to be “integrated”, and therefore it cannot become manifest in society as an expression of culture.

Remarkably, Jung understood the dream as depicting the climax of his current psychological progress. It ought to mean that psychology cannot take him further, and he must venture out into the spiritual Wasteland. But, since he had rejected the trinitarian way, he never consciously undertook that journey. It could provide an explanation for his conversion to transcendental idealism. Since the project of conscious integration had come to an end it must instead continue as collective integration, that is, as cultural realization, against the backdrop of an unapproachable heavenly realm. After all, had his journey of personal integration not come to a halt, then he need’t postulate that the archetypal world is noumenal, that is, non-integrable. Yet, during a time he closed himself into a tower like a monk, absorbed in alchemical texts. Perhaps it was an unconscious concession to the spirit.

It is evident from Jung’s dreams that the Wasteland is not a state to be overcome. Rather, it is a place (condition) to be sought, for it is the source of spirit. The Wasteland does not mean the unconscious per se. Rather, it is the spiritual condition that results from withdrawal of libido from worldly life and its cultural aspects. This is also why the alchemists discover their unpretentious spiritual stone in the lowliest of places.

In spiritual teachings the condition is associated with “perfection”, since it implies a sacrifice; to renounce life’s multitude of pleasures. However, many have mistakenly thought that self-denial and continence remains and end in itself. Rather, it serves the purpose of opening the spiritual eye with which the Platonic Forms may be perceived. The earth is “crammed with heaven”, in the words of Elizabeth Barrett Browning.

The Hermetic tradition

The Neoplatonist Iamblichus (c.245-c.325 AD) belongs to the Hermetic tradition according to which the

gods illuminate matter and are present immaterially in material things

(cf. De Mysteriis V. 23, Clarke, 2003, p. 267). In some measure, he distanced himself from Plotinus. He believed that the ascent of the soul could not be

achieved without a corresponding descent, which included theurgy

(god-work) and demiurgy (divine magic imitating the creative activity of the Demiurge). Theurgy refers to such practices as ritual and prayer, used in invoking these gods of matter. He seems to have believed

that, through this cultic practice, the soul may go through substantial

change in its very essence. So this is essentially the same idea as

medieval alchemy. The resultant effect of the symbolic practice was by

Iamblichus termed ‘theurgic union’ (De Mysteriis II.11, Clarke, 2003, p. 115). The alchemists called it the

‘alchemical marriage’, ‘coniunctio Solis et Lunae’, etc.

Although the symbols have great appeal, the average modern person is prone to regard it as hocus-pocus. The idea that we become sanctified by

partaking in ritual practices and by godly conduct is at the heart of

religion. It is equal to the notion that the “vertical striving” coincides with the

horizontal. To me, Plotinus and Porphyry appear more modern. Porphyry,

for instance, took exception to animal sacrifice (cf. De Abstinentia II.12-13).

Yet, a drawback of transcendentalist spiritual tradition is the

one-sided emphasis on the ascent to achieve ‘henosis’; union with the divine. Especially in Plotinus’s case, this is paradoxical, as he was very studious and traveled extensively.

It’s like he forgets this aspect of his personality and claims that it

doesn’t count, despite the fact that he emerged as one of the most

important thinkers in Western history.

It is a fact that we have a very strong horizontal drive in the first

half of life. It belongs in our personality equally much as the vertical

drive. Yet, Porphyry says that “the reascent of the soul is not to anything else than true being itself, nor is its conjunction with any other thing. But intellect is truly-existing being; so that the end is to live according to intellect”. (De Abstinentia, I.29). This means that the true Self is the Nous. It corresponds to the Hindu motto “atman is Brahman”. Thus, the

worldly Self doesn’t count for much. It is against this background that

we must judge the Iamblichean reaction against Plotinian

asceticism. To remedy this, Iamblichus turned to Pagan religion, the

Pythagoreans, and the secrets of ancient Egyptian priests.

So this is the Hermetic solution, which many scholars have evaluated as

a regressive development of Neoplatonic philosophy. It is only with Jung

that we get a proper programme for the horizontal expansion in life. He

defines the Self as a ‘complexio oppositorum’ and explains that

(horizontal) wholeness is achieved through a process of psychic

integration. In fact, he is fixated on the compresence of opposites.

Still, he adopts a one-sided perspective as well. He threw out the

vertical form of wholeness as if the traditions of Plato, Plotinus, St Paul,

Jesus, and Buddha counted for nothing.

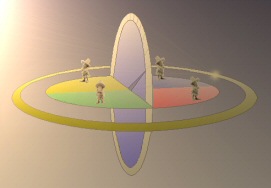

Wolfgang Pauli’s vision of the world-clock served to remedy this (Jung,

1980, p. 203). The clock consists of a vertical and an

horizontal circle, having a common centre. So there are two wholenesses

intersecting. Remarkably, Jung understood its implications very well: “[The] figure

tells us that two heterogeneous systems intersect in the Self […] We

shall hardly be mistaken if we assume that our mandala aspires to the

most complete union of opposites that is possible, including that of the

masculine trinity and the feminine quaternity on the analogy of the

alchemical hermaphrodite” (ibid. p. 205).

Wolfgang Pauli’s vision of the world-clock served to remedy this (Jung,

1980, p. 203). The clock consists of a vertical and an

horizontal circle, having a common centre. So there are two wholenesses

intersecting. Remarkably, Jung understood its implications very well: “[The] figure

tells us that two heterogeneous systems intersect in the Self […] We

shall hardly be mistaken if we assume that our mandala aspires to the

most complete union of opposites that is possible, including that of the

masculine trinity and the feminine quaternity on the analogy of the

alchemical hermaphrodite” (ibid. p. 205).

So here he says that there are two heterogeneous wholenesses. One of

them is the quaternity whereas the other is the trinity (a

Christian symbol invariably associated with vertical ascent). However, what Jung has in mind is undoubtedly conscious and unconscious viewed as two distinct systems. But it doesn’t quite tally with his concept of psychic economy;

so he soon goes back to viewing the Self as a quaternity and

forgets about the equation 4 + 3.

The diverse Hermetical traditions, which include Kabbalah, Alchemy, and Rosicrucianism, claim that the worldly and

spiritual spheres overlap rather than intersect. That’s why worldly

activities can be performed in a holy way, so as to facilitate the

redemption of the soul. A retired professor appeared on TV. He

collected beetles, I believe it was, and he had many vitrines in his home

with collected specimens. But his wife looked unhappy — I suppose because

his obsession had continued after retirement. So he was very much like an alchemist. There are people always hunting for new

orchid specimens; alternatively they might collect gemstones, for

instance. This is like the quest for the Holy Grail or the precious

lapis. The difference compared with Iamblichus and the alchemists is

that the latter conceived of a very elaborate theology around their

secret art. They also collected conceptual symbols.

At the time when Jung was about to bury himself in alchemy he dreamt

that he arrived in an Italian manor house in a carriage (Jung, 1989,

pp. 202-4). Both gates flew shut behind him. The driver exclaimed, “Now

we are caught in the seventeenth century”. Jung thought that now he

shall be caught for years. But then a consoling thought came to him:

“Someday, years from now, I shall get out again”. Jung says: “Not until

much later did I realize that it referred to alchemy, for that science

reached its height in the seventeenth century” (ibid.).

At this time his co-worker Toni Wolff withdrew, as she had no wish to collaborate

in the alchemical research. She viewed alchemy as an unappealing form of

obscurantism. Maybe she had good grounds to think so. Alchemist Michael Maier (1568-1622), author of the

alchemical emblem book Atalanta Fugiens, says that at the end of his

grand peregrinatio he found neither Mercurius nor the phoenix, but only

a feather — his pen! (referring to his copious literary achievements) (cf. Jung, 1980, p. 431). Arguably, he could have chosen any other diversion, such as

collecting beetles or gemstones. Alchemy and Hermeticism is essentially a form of personal religion that brings therapeutic benefit. But it seems to require a certain naïveté, characteristic of the collector of beetles. One shouldn’t repudiate this standpoint in spiritual matters, however. It probably suits people with a medieval makeup of personality. On the other hand, should it develop into an obsession it fulfils the same negative function as dogmatic religion, which only serves to divert the seeker from the spiritual experience proper.

Quietism versus Hermeticism

The central theme of Tao Te Ching is the reversion from the world of multiplicity to the oneness of the Tao (ch. 32) :

Once the whole is divided, the parts need names.

There are already enough names.

One must know when to stop.

Knowing when to stop averts trouble.

Tao in the world is like a river flowing home to the sea.

In the quietistic tradition, as in the Indian Vedantic school, one needs only return to one’s original place in the cosmos, since one already carries it inside — atman is Brahman. So the “emptying of the mind” becomes the focus of the adept’s efforts. The goal is to “simply be”. But is it really that simple?

In my view, the gist of the Neoplatonic message is the ascetic or renunciant orientation, and this cannot be wrong for certain people during a certain period in their life. What Plotinus introduced was the “inward turn”, away from interpersonal strife, internal agitation, and preoccupation with trifles.

Yet it seems that the quietistic model is unsatisfactory during phases of personal development. After all, we are an instinctual species for which it is hard always to remain passive. Our brains and bodies are thirsting for activity and creativity.

Accordingly, there emerged in Neoplatonism a conflict between the original quietistic model and the Hermetic model introduced by Iamblichus. Interestingly, Taoism underwent the same development. Traditional quietism, following Tao Te Ching, was succeeded by the Quanzhen school, equal to alchemical Taoism. It began in the twelfth century under the leadership of Wang Zhe. Whereas the former focuses on a return to original nature (the Tao or the One) the latter teaches the adept to transform his/her inner nature — the Self. The alchemical model focuses on cultivation, refinement, and transformation whereas quietism is dedicated to non-action and simplicity (cf. Komjathy, 2007, p. 21).

According to Plotinus and Porphyry, the human soul partly resides in the Nous, albeit unconsciously. So this means that “turning inwards” is already a return to original nature.

Since personality is sufficiently at one with the Tao or the Nous, all that is required is to achieve a “decrease”, i.e. to become simple. The adept is not trying to become something else or something more, for the soul already extends into the spiritual orb. The quietistic and apophatic concept has had an enormous following throughout history. Central to Christian mysticism (St John of the Cross, et al.) is the accomplishment of ‘unio mystica’, corresponding to Neoplatonic henōsis and Hindu samādhi. All that is required is an internal contemplative focus, together with worldly renunciation, for a lengthy period of time.

This view contrast with alchemical Taoism, and Iamblichean Neoplatonism, according to which the divine soul has fallen entirely into physis. Accordingly, a process of self-cultivation is required in order to release the celestial spirit from its material prison. In Quanzhen Taoism, the Self was seen as an alchemical crucible, wherein the work of internal alchemy was conducted, leading to immortality and perfection (cf. Komjathy, p. 98). The alchemical gold is symbolic of this purified condition of inner Self.

Thus, it was not enough to separate oneself from the mundane world and turn inwards in meditation. One must also work to refine the flawed and undeveloped inner Self, which must undergo transformation into a celestial and perfected spiritual body. It means a shift in ontological condition from ordinary human being to alchemically-transformed being. A work of self-transformation is necessary (cf. Komjathy, p. 240). This concept coincides with European medieval alchemy. So the adept must achieve a permanent spiritual state rather than having sporadic experiences of enlightenment. Interestingly, the medieval Quanzhen Taoists had a notion of “observing the internal landscape” in connection with abandonment of mundane concerns. Zhongli Quan says:

Storied terraces, blue-green pearls, female pleasures, reed pipes, precious delicacies, extraordinary luxuries, wondrous herbs, strange flowers, luminous beings, flowing radiances — each arouses the eyes like a painting does. Humans who have not awakened will take these to be a real, a sign that they have reached the Celestial Palace. They do not know that it is only the Inner Courtyard of one’s own body. (Komjathy, p. 190)

The Inner Courtyard would signify the unconscious. Apart from alchemical

transformation and mystical experiencing, Quanzhen Taoism centered very much on asceticism and renouncement of the worldly. The ascetic and contemplative praxis was at times quite austere. Thus, Quanzhen is part of the spiritual paradigm and cannot be understood in psychological terms of societal adaptation, cultural creativity, and conscious integration. Despite this, there are some interesting parallels. Late Neoplatonism and Quanzhen Taoism have many advanced and interesting psychological notions, which appear very modern.

On the negative side, Hermetic tradition resorts to naïve pagan customs, such as ritualistic activity, which do not find appeal among modern people. Is it possible to resolve this conflict between quietism and inner alchemy? I believe that modern artistic expression, such as oil painting or writing, corresponds to alchemical customs of bygone eras. James Elkins (2000) has argued that the artist’s studio equates with the alchemical laboratory (cf. Winther, 2014b, here).

Thus, it would be possible to reinterpret late Neoplatonic worship and ritual in terms of artistic expression. Rather than mixing chemicals, or making pagan sacrifice, modern people may find a corresponding symbolic activity in writing and painting. I maintain that the contemplative effort is predominantly a sacrifice to God. It is not something that must lead to samādhic ecstasy and a gratifying experience of the ego. Rather, the whole point is to tone down the ego. Thus, it is good enough if the contemplative experiences St John’s “night of sense”. A temporary ecstatic experience isn’t wrong, but it has no intrinsic value. What we are really after is a change in ontological being, conceivable as the glorified body of Christian theology. In modern terms it would imply a new and permanent spiritual condition of personality.

Faith

Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman wondered about the capability of film to capture the audience. He found it perplexing and exemplified with his film The Seventh Seal; a low-budget black-and-white film done in all haste. Still, it is considered a classic of world cinema. Despite the fact that it is an unbelievable story projected on a two-dimensional screen, it captures the viewer. Something inside us is quite capable of taking it seriously, although it is obvious that the Grim Reaper in black cloak is none other than actor Bengt Ekerot, having painted his face white. It is quite understandable that children are stirred by it, but aren’t adults supposed to be realistic and see through the deception?

It seems that we have retained a naïve faith in what we experience, although we know that it isn’t “real”. It is a function of the psyche that stays with us no matter how rationalistic and realistic we become. I believe that the phenomenon is related to the religious concept of faith. It has been argued that the “withdrawal of projections from the world” makes it a dull and grey place that no longer engages us — a Wasteland. This argument underlies the notion that the outer world must again be invested with spiritual meaning, like it was in animistic times. In postmodernist jargon, this is known as the “re-enchantment of the world”. I challenge this notion. Evidently, we still have recourse to the function of faith. This is the inner eye, capable of perceiving spiritual meaning. In a way, it can see the many living spirits that always surround and permeate us. We are capable of this despite maintaining a scientific worldview.

To withdraw projections means to realize that the figure on the film screen isn’t really the Grim Reaper — it is Bengt Ekerot. That’s why we don’t believe in a multitude of gods anymore. We recognize that the Spectre of Death does not partake in existence as a person. Yet, we are fully capable of relating to the notion, anyway, as if living the parts of the actors in the drama. Whether the rational mind wishes it or not, the spirit remains proximate. As Apollo’s Pythia at Delphi put it: “Called or not called, the god will be there”.

It seems that faith in this form must have its roots in an instinctual layer of conceptualization — the metaphorical unconscious of cognitive science. Beneath the level of cognitive awareness conceptual metaphors always operate, inaccessible to consciousness (vid. Lakoff & Johnson, 1999). At this level we are still animists. Since unconscious cognition occurs in parallel with conscious, it may function alongside a consciousness that is rational and even agnostic.

Personally, I do not experience the outer world as dull and grey anymore than I experience Bergman’s black-and-white film as dull and grey. I am still capable of visiting my favourite meadow, lush with tall grass and herbs, there to meditate about the spiritual side of existence. This is not unlike the Australian aborigine who regularly visits holy places where he prays to the local spirit. Thus, it seems that it is not the withdrawal of projections which is the problem. Rather, what diverts people from the spiritual experience is the many allures of the outer world. Our multifarious and hectic culture desiccates our soul, absorbs our energy and time.

© Mats Winther, 2015.

Earth’s crammed with heaven,

And every common bush afire with God;

But only he who sees, takes off his shoes,

The rest sit round it and pluck blackberries,

And daub their natural faces unaware

More and more from the first similitude.

(From Aurora Leigh by E. Barrett Browning (1806-61). My remark: ‘the first similitude’ is the Parable of the Sower, Mark 4.)

References

Anonymous. (1922) (Underhill, E., ed.). The Cloud of Unknowing. London: John M. Watkins. (here)

Aquinas, T. St. (1947). The Summa Theologica. Benziger Bros. (here)

Barrett Browning, E. (1979). Aurora Leigh. Academy Chicago Printers (Cassandra Editions). (here)

Clarke, E. C. & Dillon, J.M. & Hershbell, J. P. (eds.) (2003) Iamblichus: De Mysteriis. Society of Biblical Literature. (On the Mysteries of the Egyptians.)

Corrigan, K. & Harrington, L.M. (2015). Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2015 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.) (here)

Elkins, J. (2000). What Painting Is – How to Think about Oil Painting, Using the Language of Alchemy. Routledge.

Fajans, J. (1997). They Make Themselves: Work and Play among the Baining of Papua New Guinea. University Of Chicago Press.

Gray, P. (2012). ‘All Work and No Play Make the Baining the “Dullest Culture”’. Psychology Today. (here)

Henderson, D. (2014). Apophatic elements in the theory and practice of psychoanalysis: Pseudo-Dionysius

and C. G. Jung. Routledge.

Jung, C. G. (1977). Mysterium Coniunctionis. Princeton/Bollingen. (CW 14)

------- (1978). The Structure and Dynamics of the Psyche. Princeton/Bollingen. (CW 8)

------- (1980). Psychology and Alchemy. Princeton/Bollingen. (CW 12)

------- (1981). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious (CW 9:1). Princeton/Bollingen.

------- (1989). Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Vintage.

Komjathy, L. (2007). Cultivating Perfection: Mysticism and Self-transformation in Early Quanzhen Daoism. Brill.

Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M. (1999). Philosophy in the Flesh – The Embodied Mind and its Challenge to Western thought. Basic Books.

‘Noumenon’. Wikipedia article. (here)

O’Rourke, F. (1992). Pseudo-Dionysius and the metaphysics of Aquinas. Brill.

Piaget, J. (1975). The Child’s Conception of the World. Littlefield Adams. (1929)

Plato. (Jowett, B., transl.). The Republic. (here)

Porphyry. De Abstinentia. (Taylor, T., transl.) (On abstinence from animal food, 1823). (here)

Pseudo-Dionysius (1923). The Mystical Theology of Dionysius the Areopagite. The Shrine of Wisdom. (here)

Singh, K. (1997). The Coming Spiritual Revolution. Sanbornton: Sant Bani Ashram.

Tacey, D. (2013). The Darkening Spirit: Jung, spirituality, religion. Taylor and Francis. Kindle Ed.

------- (2014). ‘Apophatic elements in the theory and practice of

psychoanalysis: Pseudo-Dionysius and C. G. Jung’. International Journal of Jungian Studies, Volume 7, Issue 1. (here)

Winther, M. (1999). ‘Edinger – the ego prophet’. (here)

------- (2012). ‘Critique of Synchronicity’. (here)

------- (2014). ‘Complementation in Psychology’. (here)

------- (2014b). ‘Critique of Individuation’. (here)

------- (2015). ‘Ethical Complementarity – A Complementarian Moral Theory’. (here)