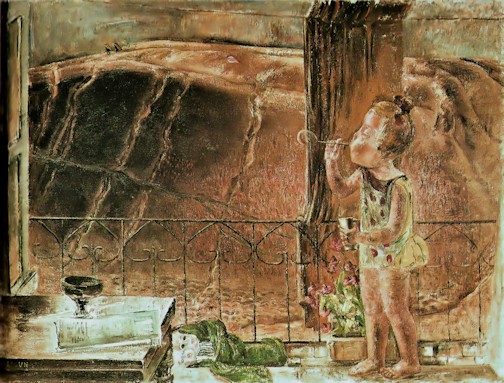

“Soap bubbles”. Vera Nilsson

(1927).

Abstract: The puer aeternus (eternal youth) is an

archetypal image found in mythology that also denotes a neurotic

condition in which the maturational process becomes arrested.

This condition depends on an inability to take root in life. In

the present era, this condition has reached epidemic proportions.

To understand contemporary societal and political changes, it is

necessary to grasp the “Peter Pan syndrome,”

which is well-known to psychotherapists. Not only does this

represent a tragedy for individuals who risk wasting their

lives — this psychological rootlessness poses

a threat to our civilization. Christianity’s influence on

Western humanity’s ethos is analyzed.

Keywords: Peter Pan, The Little Prince, infantilism,

cultural dissolution, Mel Faber, M-L von

Franz, St. Augustine, Christianity.

Introduction

Puer Aeternus first appears in Ovid’s Metamorphoses as a

reference to Iacchus, the child-god of the Eleusinian mysteries.

This divine figure, later associated with Dionysus and Eros,

emerges from ancient mother-goddess cults and represents cycles

of death and rebirth. Like similar deities across ancient

cultures — Tammuz, Attis, and

Adonis — Iacchus embodies themes of

regeneration, resurrection, and perpetual youth. The term has

since evolved beyond its mythological origins to describe a

psychological pattern in men characterized by a pronounced

maternal complex, serving both as an ancient archetype and a

modern psychological concept. A lexicon defines the term

according to psychological terminology:

Puer aeternus. Latin for ‘eternal child,’ used in mythology to designate a child-god who is forever young; psychologically it refers to an older man whose emotional life has remained at an adolescent level, usually coupled with too great a dependence on the mother. [The term puella is used when referring to a woman, though one might also speak of a puer animus — or a puella anima.]

The puer typically leads a provisional life, due to the fear of being caught in a situation from which it might not be possible to escape. His lot is seldom what he really wants and one day he will do something about it — but not just yet. Plans for the future slip away in fantasies of what will be, what could be, while no decisive action is taken to change. He covets independence and freedom, chafes at boundaries and limits, and tends to find any restriction intolerable […] Common symptoms of puer psychology are dreams of imprisonment and similar imagery: chains, bars, cages, entrapment, bondage. Life itself, existential reality, is experienced as a prison. The bars are unconscious ties to the unfettered world of early life. (Sharp, 1991)

This feeling of being fettered characterizes today’s

ideological mindset. It is now typical among leftist, feminist,

and black “liberation” groups to claim that they are

constrained by societal structures created by the oppressive

White Patriarchy (symbolic of the demanding father figure). The

demands of adult life can indeed be difficult to endure,

especially during times of economic hardship. However, when an

ideology is created from this youthful concept, society becomes

bound to produce a multitude of alienated people each year. It is

imperative that this ongoing epidemic be better understood.

Freudians call it the ‘Peter Pan syndrome,’ which is

the title of Dan Kiley’s book from 1983. (However, he

provides no references to Jungian authors who had already

researched the problem.)

The puerile form of narcissism has not yet received full

attention from the psychological community. In comparison, there

exists a vast amount of literature on the Oedipal form of

narcissism, which is connected with narcissistic personality

disorder. Whereas Oedipal narcissism is the specialty of

Freudians, the puer aeternus is the specialty of Jungians.

Marie-Louise von Franz analyzes a figure

corresponding to Peter Pan, namely “The Little

Prince” by Antoine de

Saint-Exupéry. As an archetype, the puer aeternus

represents something valuable and wonderful, although

identification with it leads to tragic consequences. An important

difference is that the puerile narcissist is decidedly more

sociable than the Oedipal type. The latter becomes a nuisance in

workplaces because the little King Oedipus has no notion

that he can be wrong, which causes problems when deciding how to

resolve matters. Yet such persons can be quite industrious. The

puer aeternus is different. I once knew a handsome and friendly

puer who, although he was an adult man, genuinely believed that

he could live without money. What need did he have for the facts

of reality? He could just as well settle on asteroid B-612, like

the Little Prince. M-L von Franz

characterizes the puer aeternus:

Precisely because the puer entertains false pretensions, he becomes collectivized from within, with the result that none of his reactions are really very personal or very special. He becomes a type, the type of the puer aeternus. He becomes an archetype, and if you become that, you are not at all original, not at all yourself and something special, but just an archetype […] One can foretell what a puer aeternus will look like and how he will feel. He is merely the archetype of the eternal youth god, and therefore he has all the features of the god: he has a nostalgic longing for death, he thinks of himself as being something special, he is the one sensitive being among all the other tough sheep. He will have a problem with an aggressive, destructive shadow which he will not want to live and generally projects, and so on. There is nothing special whatsoever. The greater the identification with the youthful god, the less individual the person although he himself feels so special. (von Franz, 2000, p. 121)

A teenage boy who refuses to accept responsibility might

become a grown man who refuses to accept responsibility. Yet not

all of them will become vagrants or alcoholics. Rather, their

irresponsibility is typically hidden behind a respectable façade.

The most characteristic trait of the puer is that he will

refrain from taking root in the present, instead continuing to

hover like a helium balloon through his life. Although the puer

is often capable of maintaining employment, he is incapable of

taking a passionate interest in his work. For example, a puer

working as a software developer will take no genuine interest in

algorithmic techniques or the advanced features of programming

languages.

Instead, he is likely to adopt a strangely indifferent attitude,

as if he were floating in the air, even when the company risks

bankruptcy. It is merely a provisional job, after all. If he is

married, that too is a provisional arrangement. The prevalence of

the puerile syndrome explains why people in the present era

change partners so frequently. Several authors have noted their

proclivity for short-lived romantic attachments (cf. Yeoman,

1998, p. 28). Neither the puer nor the puella possesses the

capacity for genuine emotional attachment. They have no strong

passion for anything or anyone, but remain dissolute and

unfaithful in the general sense — a moral

incapacity characteristic of the pueri aeterni.

The puerile society

I maintain that the puer aeternus syndrome has emerged as an

enormous problem of our time and even poses a threat to Western

civilization. It underlies the prevailing cultural and moral

relativism in the Western world. The puer aeternus refuses to

take root in our common heritage. He has no love for our great

cathedrals or for our intellectual tradition. Cultural

unfaithfulness, combined with the refusal to mature, has given

rise to an ideology of multiculturalism according to which

“anything goes.” There exists a belief that all

cultures, theories, religions, personalities, and ethnic groups

are interchangeable because they are not essentially different.

The “ideology of sameness” impedes individuation,

keeping people trapped in the kindergarten of uniformity.

Yet the current ideology of sameness builds upon a puerile form

of indifference towards culture and ethnicity. The puer aeternus,

since he lacks enthusiasm for learning, never develops a proper

understanding of anything. Among the pueri aeterni are many

politicians and journalists who remain indifferent to our

Christian legacy. Nor have they investigated Islamic culture or

delved into anthropology and psychology. It is only in their

capacity as “empty balloons,” floating above reality,

that they are able to claim that “anything goes.” Had

they acquired proper understanding, they would realize that many

differences of culture and human nature are

fundamental — contradictions and incongruities

that inevitably lead to destructive consequences.

But the puer aeternus is not troubled by such concerns. He has no

passion for our civilization, since he is essentially loveless.

Behind the façade, he feels no responsibility whatsoever for our

cultural heritage. Relativism means that there really is no such

thing as right or wrong. Conservative philosopher

Roger Scruton employs the term ‘oikophobia’

(’ecophobia’) and defines it as “the

repudiation of inheritance and home.” He argues that it is

“a stage through which the adolescent mind normally

passes.” In adulthood, it is a feature of certain,

typically leftist, political impulses and ideologies that espouse

xenophilia (preference for alien cultures) (cf. Wiki:

‘Oikophobia’).

Former Swedish Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt said in a recent

interview (Dec 24, 2014) that “Sweden belongs to the

immigrants — not the Swedes.” When

flying over Sweden, he could see that there is plenty of space

for new inhabitants (the puer aeternus is fond of airplanes, says

M-L von Franz). In a speech in Södertälje

in November 2006, he claimed that “only barbarism is

domestic” and that “all advancement derives from

abroad” (something that earned him the nickname

“Freddy the Barbarian”).

A Prime Minister who says such things about his own country and

people cannot be of sound mind. There is a complete lack of

objectivity, monumental naïveté, as well as the

characteristically puerile lack of grounding in culture. Yet

Reinfeldt, as the self-professed quisling of the modern era, is

not an uncommon example, because politics is replete with pueri

aeterni. This inevitably leads to the disintegration of culture.

The following prescient excerpt was written more than 70 years

ago by sociology professor Pitirim Sorokin

(1889 – 1968). Sorokin says that when any

socio-cultural system enters the stage of its disintegration, it

first enters a phase of inner self-contradiction in the form of

irreconcilable dualism. It soon becomes formless as it develops a

chaotic syncretism of undigested elements taken from

different cultures:

An emergence of a chaotic syncretism in a given integrated culture is another general symptom of its disintegration. The classical example is given by the overripe sensate culture of Greece and Rome. In that stage it became, in the words of Tacitus, “the common sink into which everything infamous and abominable flows like a torrent from all quarters of the world” […]

This all-pervading syncretism is reflected in our mentality, in our beliefs, ideas, tastes, aspirations, and convictions. The mind of contemporary man is likewise a dumping place of the most fantastic and diverse bits of the most fragmentary ideas, beliefs, tastes, and scraps of information. From Communism to Catholicism, from Beethoven or Bach to the most peppy jazz and the cat-calls of crooning; from the fashion of the latest movie or best-seller to the most opposite fashion of another movie or best-seller — all coexist somehow in it, jumbled side by side, without any consistency of ideas, or beliefs, or tastes, or styles […]

Viewed from this standpoint, our intellectual life is but an incessant dance of jitterbugs. Its spineless and disjointed syncretism pervades all our social and mental life. Our education consists mainly in pumping into the mind-area of students the most heterogeneous bits of information about everything […] Our ethics is a jungle of discordant norms and opposite values. Our religious belief is a wild concoction of a dozen various “Social Gospels,” diversified by several beliefs of Christianity diluted by those of Marxianism, Democracy, and Theosophy, enriched by a dozen vulgarized philosophical ideas, corrected by several scientific theories, peacefully squatting side by side with the most atrocious magical superstitions […]

This jumble of diverse elements means that the soul of our sensate culture is broken down. It appears to have lost its self-confidence. It begins to doubt its own superiority and primogeniture. It ceases to be loyal to itself. It progressively fails to continue to be its own sculptor, to keep unimpaired the integrity and sameness of its style, that takes in only what agrees with it and rejects all that impairs it. Such a culture loses its individuality. It becomes formless, shapeless, styleless. (Sorokin, 1957, pp. 241-54.)

Due to ongoing cultural dissolution, the pueri aeterni are growing in numbers. The ISIS warriors who travel from Europe to join the Islamists are mostly recruited from the puer group. They are typically portrayed as “lost youth” who have suddenly found a passionate connection with life, namely becoming part of the murderous machine. It was found that one traveler had purchased the book “Islam for Dummies” before departing, which is very telling. Probably Adolf Hitler, before he fell prey to his obnoxious shadow — during which time he lived as a vagrant and also maintained good relations with Jews(!) — can be diagnosed with the puer aeternus syndrome. The characteristic neurotic solution of the puer consists in a compulsive descent from an aeronautical lifestyle:

The strange thing is that it is mainly the pueri aeterni who are the torturers and establish tyrannical and murderous police systems. So the puer and the police-state have a secret connection with each other; the one constellates the other. Nazism and Communism have been created by men of this type. The real tyrant and the real organizer of torture and of suppression of the individual are therefore revealed as originating in the not-worked out mother complex of such men. (von Franz, 2000, p. 164)

This phenomenon explains why the pueri aeterni so commonly defame people as “Fascists” and reactionary “hardasses” — it is because they are projecting their own shadow. [1] Nazism, Communism, Islamism, and Fascism belong to the authoritarian shadow of the puer aeternus. This is the megalomaniacal phantasmagoria that serves as a new foundation when the puer attempts to leave behind his “pluralistic,” acultural, and rootless condition. Von Franz explains:

In the practical life of the puer aeternus, that is, of the man who has not disentangled himself from the eternal youth archetype, one sees the same thing: a tendency to be believing and naive and idealistic, and therefore automatically to attract people who will deceive and cheat such a man […]

As you know, Christ is the shepherd and we are the sheep. This is a paramount image in our religious tradition and one which has created something very destructive, namely, that because Christ is the shepherd and we the sheep, we have been taught by the Church that we should not think or have our own opinions, but just believe. If we cannot believe in the resurrection of the body — such a mystery that nobody can understand it — then one must just accept it. Our whole religious tradition has worked in that direction, with the result that if now another system comes, say Communism or Nazism, we are taught that we should shut our eyes and not think for ourselves, that we should just believe the Führer or Kruschev. We are really trained to be sheep!

As long as the leader is a responsible person, or the leading ideal is something good, then it is okay. But the drawback of this religious education is now coming out very badly, for Western individuals of the Christian civilization are much more easily infected by mass beliefs than the Eastern. They are predisposed to believe in slogans, having always been told that there are many things they cannot understand and must just believe in order to be saved. So we are trained to be like sheep. That is a terrific shadow of the Christian education for which we are now paying. (ibid. pp. 42-43)

Mel Faber (2010) criticizes religion from a similar perspective and alleges that “the doctrinal, ritualistic core of Christianity harbors a magical process of infantilization” (Faber, 2010, p. 19).

There is just too much supportive material [to] miss the overwhelming emphasis upon infantilizing the worshiper, upon transforming him or her into an utterly dependent, utterly submissive, utterly obedient “little child” following after the explicitly parental figures of the Almighty Lord and His pastoral Son from Whom he or she continuously seeks provision and protection through prayer. (ibid. p. 12)

Allegedly, Christian religion exploits our early experience of

being a helpless, dependent little child in the care and

protection of an all-powerful parent. The religious feeling stems

especially from the early period that is lost to our explicit

recollection. The unconscious longing for the parental figure is

projected onto the religious narrative, which acquires divine

dimensions. Thus, spiritual awareness is predicated upon

infantile attachment to an internalized, all-powerful parental

presence. Faber maintains that “it is precisely the

‘engram’ of the first relationship [at which]

Christianity aims its traditional or sacred ‘cues,’

the substance of its doctrinal and ritualistic enactments”

(ibid. p. 57). The devotee can feel the connection

within, and thus the unconscious associations have a seductive

effect, which leads to blind faith in religious narrative. The

result, Faber explains, is collective infantilization, because we

are required to adhere to the rules and dutifully propitiate the

Parental God. To be saved, Christian style, is to become innocent

as a child and to surrender wholly to authority.

Saint Augustine of Hippo

Modern Christianity, as a secular misinterpretation of historical

faith, may indeed have contributed to this trend. However, I

suggest that both von Franz and Faber misinterpret

Christianity’s historical function and role. If it has had

such an infantilizing effect, then it is difficult to explain why

Christian civilization rose to power and came to outshine all

other civilizations. Christian faith answered an inner thirst for

fellowship with the divine while also providing a predominantly

transcendental view of the sacred. St. Augustine

(354 – 430) renounces the antique ideal of

divine orderliness in the earthly realm and instead elevates the

City of God as the ideal (Augustine, 2015). He contrasts worldly

striving after power and glory, the pursuit of earthly joys, and

the grasping after transitory things with the eternal City of

God, whose citizens live according to the spirit, not according

to the flesh. The City of God, which can be acquired through

faith, “has lived alongside the kingdoms of this world and

their glory, and has been silently increasing” (Augustine,

Kindle Loc. 135).

The Earthly City, on the other hand, is divided against itself.

It is characterized by conflict, vice, and pride, and the

relentless search for terrestrial and temporal benefits. In

contrast, Augustine emphasizes ideals that transcend the worldly,

connected with the rational soul. What gives peace to the soul is

the “well-ordered harmony of knowledge and actions”

(cf. Augustine, Kindle Loc. 15769-71). Central is the

investigation or discovery of truth so that we may arrive

at useful knowledge by which we may regulate life and conduct.

The invisible spirit — which encompasses

truth, morality, and inner harmony — takes

precedence over outer societal orderliness and worldly success.

In his masterpiece, St. Augustine manages to refute the

notion of the earthly Utopia, which had become an ideal in the

Roman epoch. This change of perspective that emphasizes the

transcendent had already begun with St. Paul. It laid the

foundation for modern civilization and is also the psychological

basis for the scientific mindset.

Faber contends that becoming a child of God, subordinating

oneself to the transcendental Godhead, is the same as becoming a

naive and credulous lackey of societal authority. But the

Christian message of faith and the ideal of becoming an obedient

“little child” of God does not imply credulousness in

worldly matters. Accordingly, Jesus says: “Behold, I send

you forth as sheep in the midst of wolves: be ye therefore wise

as serpents, and harmless as doves” (Matt. 10:16). In fact,

acquiring a foothold in the transcendental

realm — the City of

God — is a requirement for authentic

psychological detachment and autonomy. The early Christians

rejected many demands of earthly authorities. Thus, it is hardly

Christian religion that has given birth to the puer aeternus.

Faber claims that Christianity represents “a magical,

prescientific mode of discourse” that serves to infantilize

its followers, “urging them to rely for security and

behavioural guidance on faith, on the existence and the

perfection of overarching parental spirits from the beyond, as

opposed to their own human reason and good sense” (Faber,

2010, p. 291). As a matter of fact, as the

“childlike” side of personality is provided for by

the church, it allows the pragmatic side of personality free rein

in the material world, precisely because the latter is being

deflated as a goal of personality. It is pointless and vain to

quest after worldly perfection in the form of an orderly earthly

paradise. Since Christianity endeavored to separate the

transcendental domain from the immanent, the gods and spirits

that dwelt in temporality, and all sorts of superstitions,

persistently dwindled in parallel with the advance of

Christianity.

Yet with the advent of modern times, people began to leave the

embrace of the church. For this reason, we have seen an enormous

upsurge in idealistic beliefs projected onto the earthly

condition. Communism and Fascism stand out as the most

destructive worldly belief systems, but the plague continues in

our current era in the form of multitudinous infantile

“-isms.” In a way, it represents a regression to

pre-Christian mentality, although pagan religious creed is now

called “ideology.” The ideologists all inhabit the

Earthly City, whose mythic founder was Cain. According to

Augustine, it is equivalent to Babylon and Confusion. Thus,

Christian faith has served as a bulwark against pagan and naive

mentality, which conflates the spiritual with the worldly. To

become a child of the Savior was the recipe for civilizational

and scientific success, as rationality, morality, and

interiority rose as guiding stars (cf. Winther, 2011).

Critics of Christianity, such as Faber, do not recognize that

tenets of faith (virgin birth, resurrection, etc.) refer not to

the earthly condition but to the City of God. Nor are critics

aware of the separate ideals of the spiritual and the transitory.

The religious message is seen as “the veiling, or the

denying, of the inescapable biological realities that not only

mark us but define us as natural creatures in the world”

(Faber, 2010, p. 193). Allegedly, it would be better to see

things as they really are rather than live a lifetime of

comforting illusions. But this is a caricature of Christian

religion, which does not consign the believer to a life of

reverie. On the contrary, human nature is seen as flawed, stained

by original sin. Worldly existence, although tolerable, is

permeated by strife, suffering, and decay. Augustine explains

that it is actually the citizens of the Earthly City who are in

pursuit of an illusion.

As for those who have supposed that the sovereign good and evil are to be found in this life, and have placed it either in the soul or the body, or in both, or, to speak more explicitly, either in pleasure or in virtue, or in both; […] — all these have, with a marvellous shallowness, sought to find their blessedness in this life and in themselves. Contempt has been poured upon such ideas by the Truth, saying by the prophet, “The Lord knoweth the thoughts of men” […] “that they are vain.”

For what flood of eloquence can suffice to detail the miseries of this life? […] For when, where, how, in this life can these primary objects of nature be possessed so that they may not be assailed by unforeseen accidents? Is the body of the wise man exempt from any pain which may dispel pleasure, from any disquietude which may banish repose? The amputation or decay of the members of the body puts an end to its integrity, deformity blights its beauty, weakness its health, lassitude its vigour, sleepiness or sluggishness its activity, — and which of these is it that may not assail the flesh of the wise man? Comely and fitting attitudes and movements of the body are numbered among the prime natural blessings; but what if some sickness makes the members tremble? […] What shall I say of the fundamental blessings of the soul, sense and intellect, of which the one is given for the perception, and the other for the comprehension of truth? But what kind of sense is it that remains when a man becomes deaf and blind? where are reason and intellect when disease makes a man delirious? […] And what shall I say of those who suffer from demoniacal possession? (Augustine, Kindle Loc. 15409-29)

Modern infantilism does not stem from Christianity. Rather, I

theorize that many pueri aeterni are essentially different from

the mature Western personality. They live in a radically

different conceptual universe, as if floating around in a bubble.

Psychoanalysis has always underestimated the constitutional

differences among human beings. I believe that

“patriarchal” personality, denoting the

individuating personality, is essentially different from

“matriarchal” (mother-bound) personality. The

principle of individuation takes root in early childhood and only

in certain individuals. So the matriarchal personality does not

‘evolve’ into the patriarchal because it represents a

different branch of the human tree. The two human branches

correspond to the City of God and the Earthly City.

I would characterize many adult men in the Western world as

‘dorks’ or ‘drones.’ In my country, they

have ascended to power in government and institutions. As

criminal psychopaths ruled Germany in the thirties, so do the

drones rule much of the Western world in the present era. They

are like little twigs, little phalluses, on the trunk of the

Mother tree. Their personality resembles that of a

twelve-year-old who will never truly adapt to reality, mentally

remaining in his boyhood room. Such people are

“playing” a boyhood game in which the world is

Mama’s paradise, where motherliness and multiculturalism

prevail. The drones are almost like a different species that the

church managed to enclose in its garden but which is now

ascending to power. Arguably, they have always been present. It

is just that they have, through societal changes, become more

conspicuous in modern times. Immigration contributes to a

considerable increase in their numbers.

Oscillation between dependence and

independence

Drawing on anthropologist Victor Turner’s work on ritual

and social structure, Bruce Reed (1970) identifies two

contrasting social models: the differentiated and structured

relationships of everyday life, and the undifferentiated and

homogeneous relationships found in ritual activity. Societies

oscillate between these states, with religion serving as the

vehicle for temporary regression to dependence that subsequently

enables renewed engagement with structured social life. This

observation appears to corroborate the preceding analysis.

Individuals naturally transition between states of dependence

(where they can recuperate and regain strength) and independence

(where they actively engage with the world). Reed contends that

this cyclical pattern is essential for psychological health.

Religious gatherings create environments that express dependence

(as demonstrated by von Franz and Faber) while

simultaneously providing frameworks for evoking, expressing, and

regulating emotions.

Reed conceptualizes this oscillation as movement between chaos

and cosmos, emphasizing that authentic faith can guide

congregations towards controlled regression, thereby enabling

their return to structured society with enhanced autonomy and

moral authority. He argues that the Church’s function in

society is to address people’s dependency needs. While many

contemporary thinkers advocate for humanity “coming of

age” and outgrowing dependence on God, psychological

research suggests that genuine independence and maturity actually

depend upon underlying security and dependence. A

“childlike” dependence on God enables autonomous

functioning within society.

The puerile ideal of pluralism

The theory around the puer aeternus can also help us understand

why Jungian psychology has difficulties advancing to a

respectable academic level. By all evidence, psychology, much

like politics and journalism, is being swamped by pueri aeterni,

or at least people poisoned by the “pluralistic

relativism” of our times. Thus, a well-known Jungian

analyst and author can say:

For me, Jung has left behind a number of wonderful toys which I can carry into my playground. This Jungian inheritance is mixed together with toys left behind by Freud, Klein, Bion, Winnicott, Kohut and many others. My “Jung” wanted us to play with these toys, mix them up, make new things with them, and invent new games. My “Jung” did not want us to mummify, safeguard, or enshrine his ideas — but I believe he did want us to embrace the spirit of inquiry that all of his ideas emerged from. (Winborn, 2015)

Moreover, a well-known Jungian analyst has proclaimed

“the diversity of psychology and the psychology of

diversity” (Samuels, 1989, ch. 12). Yet he has

effectively refuted the idea of theoretical pluralism because it

is somehow obvious that it cannot work. The scientific community

would dismiss it as whimsy since it flies in the face of the

empirical paradigm. However, the puer aeternus has no problem

with this because he has no passion for science or for the

Platonic and Aristotelian pursuit of truth. Science is merely a

way of “toying” with the plurality of theories while

traveling in one’s balloon. It requires a superficial

attitude, which means that theories are not properly understood.

In fact, they are genuinely contradictory. Many are

scientifically obsolete, while others have harmful consequences

for the patient. Of course, thinkers of this ilk do not care

about the future survival of psychology. The puer takes no real

interest in its theses anyway. He has no desire to dig deeper, to

substantiate and develop psychological theory. To the puer, all

things are toys, like pieces on a game board.

Psychologist James Hillman prided himself on being a puer

aeternus, whereas Jungian analyst Daryl Sharp and

psychoanalyst Dan Kiley both claim to have overcome their

condition. It is evident that the puer aeternus problem is

increasing. It is sometimes difficult for immigrants to adapt to

a new culture, which leads to rootlessness. M-L

von Franz criticizes the way in which modern welfare

society infantilizes its members through economic dependency.

Moreover, our culture seems to generate a mentality of fantasy

and ideology. The puerile community is very fond of nebulous

words like ‘multicultural dynamics,’

‘oppressive structures,’ and ‘complex and

multidimensional.’ Society is viewed as a huge multifarious

hodgepodge that cannot be analyzed. In this way, one need not

relate to the facts of reality.

Much of today’s societal problems stem from a psychogenic

incapacity for growing up. Rather than developing realistic

consciousness, many citizens remain idealistic in the naive

sense, retaining the immature and utopian mindset of adolescence.

This implies that consciousness is being infected by the

unconscious fantasy world, as conscious and unconscious are not

sufficiently separated. To subscribe to an ideology and to have

utopian ideals — that is, to live in a fantasy

world — is characteristic of many modern

citizens. It is characteristic of the pueri aeterni who remain

unaffected by the facts of reality. It was this very mindset that

St. Augustine successfully attacked by achieving a

separation of spiritual meaning and worldly existence. This

served to untangle consciousness from the archetypal imaginary

realm.

Could there also be a genetic component to this puerilization?

Historically, women’s economic dependence meant they

typically married ambitious men capable of supporting a family.

With women’s economic independence and the social safety

net, mate selection may now prioritize different traits, such as

physical attractiveness or social charm, rather than traditional

markers of financial stability or ambition. This shift in

selection pressures could theoretically influence population

genetics over time.

The remedy

Carl Jung argued that “hard work” is the remedy. It

does not merely serve the function of societal adaptation. It is

a way of becoming absorbed in something, which means that one

takes root in unexciting existence rather than hovering like a

balloon. Yet Jung and M-L von Franz

question whether hard work is always the right answer. Jung also

had a notion of “going through” the problem rather

than finding a resolution. In this way, one may emerge healed at

the other end, having thoroughly passed through the neurotic

phase. This reminds me of Wim Wenders’s road movies.

Perhaps a puer aeternus should try to immerse himself in the

problem by leading life like a vagrant, moving from motel room to

motel room in a thoroughly provisional existence. During this

phase, he is “totally committed to being a vagrant,”

which creates an interesting oxymoron.

However, I submit that St. Augustine’s time-honored

solution — to acquire a spiritual and

trinitarian passion — remains the foremost

remedy. The movement towards a transcendental ideal, inaugurated

by Christianity, caused the demise of religious worship of the

many immanent divinities of the classical era. It effected the

disentanglement of consciousness from the archetypes of the

unconscious, which was necessary for the advancement of realistic

consciousness. The mother complex implies that the conscious ego

is stuck within the motherly unconscious. My point is that the

separation of spirit and world causes a detachment of conscious

and unconscious. It constitutes a remedy against the mother

complex, of which the puer aeternus and the Oedipus complex are

different forms. The trinitarian form of mysticism requires

renunciation of the worldly and a more or less ascetic lifestyle.

It serves to rise above worldly identification. Arguably,

St. Augustine’s countermeasure against worldliness

remains a workable solution to the problem of the puer

aeternus.