Critique of Individuation

“Seagulls at the beach”. Alexander Camaro (1951).

Abstract:

Individuation as the process of psychological maturation is associated with the way of the spirit, equal to the ‘narrow path’. Social and worldly adaptation as central aspects of individuation are overvalued. It is generally held that symbolic transformation of unconscious images fulfils a therapeutic function. This view is criticized as a way of upholding the stagnant ego. On the contrary, transformation must be authentic. The notion of ego abandonment in spiritual tradition should be taken seriously. Central to psychology is the integration of the unconscious. But equally important is the opposite process of ‘complementation’. Consciousness is not only synthetic; it has also a ‘sympathetic’ function. Consciousness can give life back to the unconscious and not only empty it of its goods. To this end, a creative form of contemplation is recommended, in the manner of painting or writing. The destruction of the stagnant state of personality, and the riddance of aspects of personality, are part and parcel of individuation. Today, adaptation and assimilation are overvalued whereas negation is undervalued. The Self in Jungian psychology is a towering ideal, a conglomerate of contradictory aspects of personality. At a point in time, the spiritual seeker must abandon the ideal of completeness and begin to negate his profane obsessions, which are nothing but meaningless games of life. At this juncture, the passionate game of creativity is ushered in.

Keywords: critique of Jungian psychology, integration, complementation, negation, destruction, spiritual path, art, individuation, apotheosis, alchemy, Gnosticism, Holy Grail, C. G. Jung, Emanuel Swedenborg, Poul Bjerre.

Introduction

It seems that life has a “game-playing” foundation. The most pronounced characteristic of human nature is a fondness for the manifold games of life. Historian Johan Huizinga (1971) goes as far as naming our species ‘homo ludens’. Human activities, in the form of professions and careers, are qualitatively different. Some are, in the short

perspective, more beneficial to society, but not necessarily to the natural world. Yet, there’s no essential difference between

the careers of sports, scientific research, film stardom, politics, etc.,

because they share the same “game-playing” foundation. The

share market is a kind of game, and so is the whole competitive market

system. Whatever we do, we are merely partaking in a meaningless game,

spurred by unthinking forces of instinct. Like energetic hamsters we are running around on the game board of life. While

swimming with the tide, life’s forces shuffle us around. It’s an apt picture of professional and matrimonial life. In our careers and endeavours we are unthinkingly devoted to playing life’s game.

Although it captivates and engages us to a remarkable degree, the perpetual game-playing must be regarded an essentially purposeless activity. It gives birth to the idea that we should step out of the hamster wheel and stand apart from the onrush of life. Of course, this is nothing new. The achievement of worldly transcendence is central to the spiritual traditions of the world.

Arthur Schopenhauer argues that humanity is

driven by a dissatisfied Will, continually seeking satisfaction. Human

desire and all human action are futile, illogical, and directionless. To

Schopenhauer, the Will is a malignant power that arises from insentient nature and imprisons us in the hamster cage of life. His answer is

that we must escape the Will by standing apart from life. It is achieved

by way of methods of transcendence, such as asceticism and chastity. But

since Schopenhauer lacked a positive notion of

individuation [1] as a complement to the negative compulsion of the Will, it took the reverse expression in an hedonistic lifestyle among

his followers. Since life is essentially without purpose, we could just as well enjoy ourselves while remaining on this earth.

Carl Jung, being averse to asceticism and chastity, took Schopenhauer’s

insensate Will and turned it into the positive force of

individuation.

From a standpoint of worldly abstinence, it is as if Jung endorses the “hamster wheel of life”. Yet, since his consciousness

is modelled on the

ambivalent Self, he is also capable of seeing life’s

failure as the inception of individuation in the way it promotes

self-knowledge. He expands life’s game by inventing the individuative

journey as the successive integration of

archetypes [2] by the method

of

active imagination. [3] Concepts of individuation and the

realization of the

Self, [4] as they go inwards and outwards at the same

time, are contradictory and unclear, and many can’t seem to make

heads or tails of them.

Thus, Jung has revamped the spiritual path as the journey of individuation. On the one hand, there is a focus on psychic integration; on the other, it remains essential to partake in earthly existence to the full, as the goal of integration is the acquirement of the complete humanity of the Self. The traditional notion of worldly transcendence is reinterpreted as a temporary period of introversion, involving a confrontation with the archetypal domain. However, in the following I shall argue that it risks becoming yet another game-playing activity.

The towering ideal of Self

The

Self is defined as a teleological goal. The

telos of the Self implies that the ego is pulled towards

the Self whose gravity is always increasing during individuation.

The Self is viewed as a paradoxical and multifarious wholeness, harbouring many conflicting

opposites.

Arguably, since individuation as a concept elevates the multifarious wholeness of Self as an ideal for the ego, self-absorption could be the consequence.

Rather than depending on the telos of the Self, I suggest that individuation depends

on spiritual ambition, which is essentially different than secular fulfillment. Notions of worldly transcendence, deriving from time-honoured religious tradition, are as valid as ever before. For this reason, it is necessary to disentangle the non-secular path from the notion of individuation and introduce a notion of

spiritual individuation.

The Self is a towering ideal, representing the integration of conscious and unconscious, mundane and

extramundane. Arguably, the notion of Self is overbearing, as it represents the ideal to

encompass

both social existence and the unconscious psyche in yet more intense and

also broader relationships (cf. Jung, 1977, para. 758). In theory, demands are put on the individual that require an inordinate power of personality. However, we cannot possibly be well-adapted individuals in society,

having recourse to a full-fledged family and social life as well as a

thoroughgoing relation to the

spirit — not at the same time, at

least. Jung’s

ideal of Self is associated with “completeness” and he argues strongly for it,

repudiating the ideal of “perfection” (cf. Jung, 1979, pp. 68-70). It amounts to

“lifting up one’s cross”, carrying it along in life.

He says that “[only] the

‘complete’ person knows how unbearable man is to himself” (Jung, 1977b, pars. 1095f). The conclusion is that huge and contradictory demands are put on the individuant.

The majority of people are occupied with the problem of how to amuse themselves this

very day, or how to promote their own social or economical

status. Yet some people have another drive.

Marie-Louise von Franz (1915-1998) holds that the

spiritual drive is even stronger than the sexual. Such a devotional drive, corroborated by the tremendous prominence of esoteric and ascetic tradition, would seem to make the

telos of the Self redundant. Why some

people have more of it than others is another question. It’s evident that suffering plays a prominent role. Has anyone, who hasn’t been sick or deprived in some sense, ever succeeded on the godly path?

It’s evident that the earthly allure has a harmful influence on spiritual development, which explains the enormous focus on poverty and suffering in religious tradition. We have a tendency to become overly absorbed in secular matters, with the consequence that the faint and godly energies vanish from sight. The sense of mystery is easily lost.

Individuation is something quite different than self-fulfillment and

self-realization, which is the subject of many a book. Whereas earthbound

success is like being transported on the diverse currents of life,

especially as formulated by societal life, spiritual individuation depends on

another kind of drivenness. I think of individuation as a pious devotedness

that has its source in the unconscious, which means that it is

independent of religious doctrine.

Yet, Jung’s version of individuation is to play the game to the full,

both in its inner and outer sense. He inscribed the following verse

in Greek on a stone, and it’s also how he ends his autobiography:

Time is a child — playing like a child — playing a board game — the

kingdom of the child. This is Telesphoros, who roams through the dark

regions of this cosmos and glows like a star out of the depths. He

points the way to the gates of the sun and to the land of dreams.

Thus, the Self is portrayed as a gamester who points the direction to

daylight existence and the moonlit realm, simultaneously. Telesphoros means ‘fulfillment-bearer’.

The

anima/animus, [5] as archetypal personification of the unconscious, plays an important part in psychic life. Yet, it is also the fabricator of

illusions — the veil of

Maya — which might explain why Jung always looked upon the

anima with suspicion. He had in a sense fallen for her deception.

She creates the illusions which keep us bound to the games of life. For example, the game of

chess is subjected to an anima projection, which serves

to enslave the chess player to the game (to his own contentment). The

anima is projected on the psychological theoretical edifice, too, providing us

with an eminent hamster cage. We are being deluded; but this is how life

is. It is not really evil, but it’s a functional and probably necessary

phase.

The giant and the two skyscrapers

Individuation, understood as emancipative achievement, or worldly transcendence in religious language, is brutal and nothing must stand in its way. This seems to be the

message of the unconscious. The following dream of a middle-aged man is thematic.

A giant, several hundred meters high, is attacking

a skyscraper, but he lets the other skyscraper be. Debris was falling all

around me, and people fell to the ground and died. I took a long

roundabout route, outside the view of the giant. During the journey I

fell blind during a time, but finally managed to enter the safe

skyscraper. From the bottom floor window in the safe skyscraper I could see that

the giant wore washed-out blue jeans.

The “spiritual” skyscraper was

undergoing construction, and it was determined to overcome the doomed

skyscraper. The skyscraper being demolished represents earthbound and ambivalent

life whereas the other one represents inner life. Meaningless

mundane obsessions and preconceptions fall to the ground and die. The

giant presumably represents the towering force of individuation, which cannot be stopped.

The first skyscraper is like an illusory and grand

“hamster cage”, in which the ego scurries around on the many floors and

joyfully tries out the different hamster wheels. The gist of my argument

is that individuation, from the beginning, seems to continue

independently alongside the construction of an illusory

anima life, yet

in the form of a second skyscraper undergoing construction. The upshot is

that transcendental individuation is to be taken very seriously, because it has its roots in powerful insensate nature. It is so central that nothing else

counts. It is a giant that crushes to

smithereens the painstakingly constructed skyscraper of consciousness.

According to the view here proposed, individuation runs invisibly in the background, as it were, in

parallel with Schopenhauer’s formative Will. But when the adaptational

function of the latter has served its purpose it becomes only an

impediment, and the structure must be dismantled. Thus, the spiritual pilgrim

must stand apart from illusory life, in the way of Schopenhauer. The

difference is that the individuant now has recourse to the completed second skyscraper, which represents individuation proper. Personality needn’t be ambivalent anymore.

Thus, there seems to be two complementarian aspects of Self and two

parallel paths of individuation, one illusory and one true, the first of

which must be terminated. On the other hand, the problem with the Jungian edifice is that

it’s conglomerative, something which leads to deleterious consequences.

For Jung, there is only

one skyscraper and there is only

one Self.

Taking part in purposeless life while performing

inner work constitutes

a conjugate, since it gives expression to completeness and the

conglomerative Self. However, there are really two skyscrapers, the

first of which must be razed to the ground because it has turned evil,

although it wasn’t from the beginning.

The complementarian Self

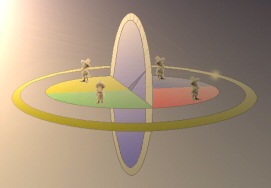

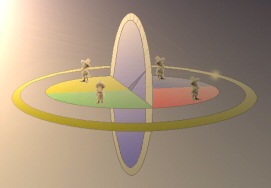

Joseph L. Henderson takes the view that individuation is predicated on the shamanic journey. He adds to the picture the “Ultimate God Image” as a complement to Jung’s view of Self, namely the “Primal God Image”, portrayed as an “ambivalent monster” (cf. Henderson, 2005, p. 226). The shamanic journey takes place as a circular movement between these two poles:

Here, the transcendental movement means to transcend the earthbound in its guise as the “Primal God Image”. However, it does not signify a polarization of secular and non-secular in the metaphysical sense. In the above dream, the giant is destroying the very same “ambivalent monster” as carrier of our conceptual objects of worship. It is a terrestrial God Image, a pagan image of idolatry. Striving after transcendence serves the purpose of emancipation; to free personality from the idolatrous aspects of consciousness.

When the conscious ego-structure has played out its role it goes the way of all flesh. Personality is relieved of everything that it believes in, which has kept personality and its creativity captive. What remains is the heavenly blue yet chthonic spirit, the indwelling spirit, which the alchemists called Mercurius. It is a pseudonym for the Holy Spirit, or the Christchild. It’s no longer a hypostatized object of worship, but a spirit of creativity rooted in insensate nature, which allows personality to relate to existence in a profound sense. When we think that we are being worldly-minded and relational, we in fact miss the essence of reality. Sometimes it seems we are only rushing by in a hurry. As extraverts use to say at a ripe age: “Oops! Was that Life that just sped past me?”

In Henderson’s diagram, I think that the downward movement means a return to the Primal God Image in its guise as the Earth Mother, which here takes the meaning of bodily death. The upward movement of detachment would signify ‘the assimilation of the alchemical Mercurius as the spirit of individuation’, leading to a creativity that is unpretentious and rooted in the insensate mind.

The Mercurius, as the heretic god of medieval alchemy, seems to represent the force of love as

present in the lives of people, whereas the Christ represents the hypostatization of love as

transcendental object of worship. The Mercurius is merely another name

for the Christchild. I hold that it symbolizes the

primus motor of individuation as

the force that invokes and sustains the path of individuation in the

lives of people, and which always attempts to break the gridlock.

Such a development necessitates that the world of the “ambivalent monster” is thoroughly abandoned. Nevertheless, the Primal God Image remains a necessary phase of individuation. We cannot start out without a platform of concepts and beliefs, serving the constructive purpose of strengthening our consciousness. Although psychology provides us with a good conceptual platform, later in life it may inhibit the powers of emancipation.

Thus, in the ongoing race of construction, the first skyscraper takes the lead, as a necessary factor of personality growth, but the second skyscraper is destined to overcome it. As the latter reaches a certain elevation, it is time for the giant to step in and demolish the

earthly skyscraper. It is earthly in the sense that it keeps us bound to the Primal God Image, that is, the Jungian earthbound ideal of Self and concomitant idolatrous concepts of consciousness. Instead of giving them metaphysical status, almost as objects of worship, we must instead realize that it’s “grey theory”. As such, it is of the good, until the time arrives to loosen the mooring.

The Primal Self Image is an ‘ambivalent monster’. Should the individuant remain stuck in its claws, he may not emancipate personality and truly participate in life. As a consequence, life rushes by without him taking root in existence. It is paradoxical in the sense that “grey theory” isn’t really invalid. It just isn’t useful anymore, but has become an enemy of individuation.

Thus, Henderson’s diagram seems to point at a radical transformation of personality, since it portrays our psychology as harbouring two competing selves, the primary of which must be abandoned. I discuss this notion in my article ‘The Complementarian Self’ (Winther, 2011,

here).

Although the second skyscraper has long undergone construction, supported by an ambivalent consciousness, it is now time to remove its competitor, because egoic consciousness impedes its completion, a circumstance that leads to

stagnation.

Poul Bjerre

The theme of coercion in terms of life’s obligations and necessities

versus the liberation of the life spirit was central to Poul Bjerre (1876–1964).

Bjerre’s notion of

death and stagnation, to be overcome by an effort of renewal, remains central in human psychology, although its misinterpretation in Freudian theory as the “death drive” has rendered it a resting-place on the churchyard of psychoanalysis.

He belonged to the first psychoanalysts; but in 1913 he chose to break away from

the Freudians. Regrettably, few of his books have been

translated to English. His philosophical book “Death and renewal” (his intellectual

legacy) is much different from his

pragmatic explications of clinical psychology, which revolve around the

same theme, namely how the coercive forces of life give rise to

mechanization and psychological death. The life-draining force of stagnation

must repeatedly be overcome by a psychic renewal. Should one get stuck,

it may give rise to obsessive-compulsive afflictions or neurosis.

Freud took Bjerre’s notion of the death-renewal cycle and reinterpreted

it in terms of the

death drive versus the

eros drive. Probably he

thought that he had thereby foiled Bjerre’s competing

school of

psychosynthesis, but he had also made nonsense of the notions

and made them indefensible in biological terms.

It seems to me that Bjerre’s views could inform modern psychology, especially since his

successful therapeutic approach is bolstered by modern developments in

therapy. In Bjerre the individuative demand is toned down. Instead, it is regarded an

autonomous function of the psyche, searching to acquire harmony and

wholeness, building on experiential contents and future

possibilities. It is our natural biology, which serves to further the

chances of good health and survival. Thus, the dream function attempts

to overcome stagnation and to further growth to new possibilities of

life. It always revolves around the dichotomy of stagnation and renewal. Yet people tend to get stuck in

the transitional phases, which could result in neurosis.

Thus, his view of psychological growth is different than the Jungian

view. The latter is teleological in that individuation strives to realize the

goal of an ideal Self, formally indistinguishable from the God image.

The Christ as a symbol of the Self is in itself a dichotomy,

incorporating the little suffering man and his opposite in the form of

the all-powerful Christ Pantocrator. Nevertheless, the Christ isn’t

complete enough, according to Jung. The Self is an ambitious goal of

personality, which implies both secular fulfillment and deiform

elevation. One might question why evolution should have endowed us with

such a individuative drive. Biologically, it is hard to explain. But

Jung has absorbed Gnostic and Neoplatonic religious ideals and reformulated them in earthbound terms.

In his book

Drömmarnas naturliga system (Natural system of dreams)

Bjerre, among other things, gives a few examples of the monogamous-polygamous conflict. He exemplifies with dreams of patients

where the monogamous and matrimonial solution is sought by the

dream function. This, of course, gives the lie to the Freudian instinctual

and polyamorous wishes. The question is why the unconscious mind should side

with monogamy. The answer is that it searches to achieve

harmony and to avoid inner conflict. After all, there is nothing as

disruptive and splitting as polyamorous adventures, when one’s feelings

become divided. The social consequences are damaging, especially in

Bjerre’s own time. Bjerre has termed this natural tendency

‘assimilation’. It searches to assimilate the different aspects of the

individual, including the forgotten events that carry exuberance of life, in order to create a harmonious whole, so that the individual may have

recourse to his/her full vigour and feeling for life. Thus, growth of

personality and individuation occurs as a corollary of the natural

tendency of stagnation (such as a stagnated marriage) and the natural

tendency to overcome stagnation, achieving a renewal of life. Arguably,

individuation can do without the teleological goal of attaining the Self

in all its humanity and divinity, on lines of the mystical ideal.

In terms of Bjerre, the forces of stagnation depend on a mechanization of

life typically brought about by a fixation on tenets of consciousness.

Arguably, the way in which Jungian psychology depends on a rather

overbearing metaphysical edifice, it might have psychological stagnation as

a consequence. If individuation is regarded as the

telos of the magnificent Self rather than depending on pragmatic

emancipation of life’s energies, in whatever form, then it represents a

hypostatization of spiritual emancipation, as in the world religions. If the tenet of

individuation is worshipped rather than lived, then psychology has acquired religious overtones.

Bjerre exemplifies with a young Christian man whose highest ideal was to

evangelize among “the Negroes”; but he was waiting for a calling from

God. He had been brought to a neurotic standstill, working with office

duties that were below his intellectual level (cf. Bjerre, 1933). Bjerre sent him on his way, despite the fact that he despised

the notion of Christian evangelization. He reasoned that this man might

in the future come to his senses, but only provided that the deadlock is

broken. One must “strive after an emancipative development”, no matter

what form it takes. It is a highly pragmatical attitude, similar to how

a sapling must for a time grow in the “wrong” direction in order to

reach the light. On account of his pragmatism, analysis didn’t continue

over many sessions, but was continued in correspondence. To get the

juices flowing is central. But how would a modern analyst have treated

this patient? Arguably, he would have been subjected, directly or

indirectly, to the many metaphysical tenets of psychology, in an

attempt to “win him over”. Let life have its way, instead.

Thus, individuation isn’t entirely predetermined according to psychological law. By

example, if painting geometrical abstract art is the way that the

dream function suggests, then it’s the right way, because it releases

libido, stimulating a movement out of stagnation. It doesn’t matter

that it gives the lie to the Jungian symbolic process. Although the unconscious psyche

has an innate structure, individuation cannot be pinned down.

Anything goes, as long as we make headway. The giant in the skyscraper dream held a

huge broken off portion of the building and shook the many conscious

preconceptions out of it, with the consequence that they fell to the ground and died.

Examples of such are preconceptions along lines of psychological

telos and the technique of making headway on the path of

individuation.

Negation and destruction

To be undivided means to have recourse to our full resources. It promotes health, both psychological and bodily. The psyche strives autonomously to heal us in this sense. But it’s not that simple. After having attained a stage of stability and relative wholeness, we will soon find the forces of routinization and stagnation taking over. So it goes with everything; religions, marriages, social networks, and especially the individuated person.

According to Bjerre, this is the birthplace of neurosis, which gives rise to dividedness. The psyche wants to overcome stagnation, and it starts to break up the lifeless wholeness. Thus, the psyche works both ways: there is a dynamic interplay of the forces of death and renewal. Wholeness eventually leads to death, which must be overcome.

When people become stuck in the transitional phase, it has neurotic consequences.

People often dream of having a complete row of teeth; but then they start to drop out. This is a typical “negation dream”. It means that the wholeness achieved is negated and that which has become rooted in the flesh must be removed. New teeth will grow out instead. In the aforementioned dream, the first skyscraper is like a row of teeth that must drop out. It’s a wholeness become stagnant that must be destroyed. The reason why it takes this monumental archetypal expression is because stoical and long-suffering consciousness needs to be convinced, in a brutish way, that the present situation can’t be right. It is a very common problem, having to do with the centrality of ‘faith’ and ‘faithfulness’ in our culture.

For Jung, there is only an archetypal impetus toward wholeness. He turns a blind eye to the motif of destruction, which could be denoted the Hegelian fallacy. In fact, the destructive force is part and parcel of individuation. Any wholeness, regardless of its richness, is a cocoon that must sooner or later crack open and give birth to something new. Stagnation, and possibly neurosis, occurs when we remain stuck in the cocoon. It gathers mould instead of breaking up.

His notion of Self as unitarian means that it envelopes both ego and non-ego. The ambivalent ego is modelled after this criterion.

Thus, the Jungian notion of Self it violated when ambivalent wholeness is being negated. But this is the way of mystical tradition; the ideal of “self-abandonment to divine providence”. At some stage, self-abandonment becomes necessary, at least to a moderate degree, otherwise it leads to death and stagnation. The notion of ego abandonment, in Eastern philosophical terms, is misinterpreted by Jung. From a psychological point of view, transcendence mustn’t be understood as a metaphysical and religious concept. Rather, it means transcending the ego in its present constitution. In his critique of yoga and Eastern spiritual discipline, Jung interprets ego transcendence as the catastrophic abandonment of the conscious function. Against this critique, Leon Schlamm says:

During transpersonal states of consciousness the ego is not abandoned, nor completely transcended; rather, the spiritual practitioner realizes that the ego lacks concrete existence. It is not the ego that disappears; rather the belief in the ego’s solidity, the identification with the ego’s representations, is abandoned in the realization of egolessness during states of ordinary waking consciousness. (Schlamm, 2010)

Jung’s ardent defence of the egoic structure is misguided, because its consciousness is not the same as its structure. As he formulates it himself, the ego is merely the centre of consciousness. The ego cannot enhance its light endlessly, incorporating yet more realizations of the unconscious. There’s a limitation to the elevation of the first skyscraper, because stagnation ensues and there’s ‘negation’ piling up in the unconscious. (However, according to Bjerre, when religious tradition elevates ‘negation’ to doctrinal status, the devotees tend to get stuck in that phase instead.)

The theory of unconscious compensation

Dreams on the theme of negation are difficult to understand from the Jungian perspective of compensation. “What does this dream compensate?” Thus, it is taken for granted that there’s something wrong with the conscious standpoint; but it isn’t necessarily so. In fact, we must sometimes search to overcome a wholeness that is become complacent and listless. The only thing that counts is that life is flowing. People who are overly fond of alcohol and merry festivity tend to dream that they meet an alcoholic bum on the street. Understood in terms of compensation, i.e., as a way of contrasting consciousness, it would mean that the dreamers’s qualms about his alcohol consumption is exaggerated, as there are people worse off. Or if it’s understood in archetypal terms as the shadow, then it would signify his innate nature, which he can only keep on a tight rein but not get rid of.

In terms of Bjerre, such dreams are really ‘objectifications’, which serve to put the alcoholic and festive aspect of personality on the outside, as non-ego. It is not ‘me’ but another person. It has an immediate benevolent effect, because the dreamer begins to loosen his attachment to this particular aspect of personality. Should he dream that the alcoholic bum goes to Japan, then it’s termed ‘distancing’. Should he die, then it’s negation proper, i.e. like losing a tooth (cf. Bjerre, 1933, pp. 178ff).

The fact that therapists have to struggle with the notion of compensation as only tool is unsatisfactory. The Jungian theory of dream interpretation is rather simplistic. What’s worse, the therapist might apply the method of ‘amplification’ and associate the drunken bum with mythological themes, such as Bacchus the wine god, or whatever. It leads away from the concrete dream material in the same manner as Freudian free associations. The method is worthwhile provided that the archetypal theme can be connected to personal material. Yet, dreams seldom focus on the archetypal aspect. They generally refer to personal life and not to the life of our species.

Dreams often serve to strengthen the conscious standpoint. It gives the lie to the notion of compensation as the master key of dreams. It has to do with the fact that consciousness is conflicted. Although personality has already made up its mind in a sense, for various reasons it remains stuck. For instance, it could be due to insecurity or inertia. It could be the question of a bad personal relation that needs to be terminated. In such cases dreams can tell the person what he or she already knows, in the so called outline dreams (‘gestaltning’). The way in which dreams outline the situation and certifies that the conscious view is right, is a valuable function. It makes the ego strengthen its resolve, enabling it to see things more clearly. Consciousness is often only ‘almost’ certain, but the fog will soon be lifting as rational understanding is supported by feeling. Personality is freed of the remaining illusions.

The ego needs support from the unconscious, and not only opposition and correction in the form of compensations. Often the dream function supports the wholeness achieved by an endowment of feeling, perhaps with a religious overtone. The conclusion is that the dream function is generally synthetic and not generally compensative, since it strives to alleviate the conflicts of personality and to enliven consciousness. When lust for life peters out, and the present situation is insupportable, the Self will attempt to break up the stagnant wholeness in order to invoke a new development, which has long been in the making as a parallel building project.

The stagnant ego castle

The theory around individuation and the dream function is rather abstruse and the theoretical blueprint is inadequate. The Self isn’t working single-mindedly towards wholeness. Wholeness must be destroyed, if it is become like an oxygen-depleted pool, void of life. Should the ego lead life in a beautiful castle yet with boredom approaching, then it’s time to leave the castle for a hut in the wood, among the wild animals, if this is what it takes to keep libido flowing. This is the way of Prince Siddhartha Gautama and many other an ego-transcending ascetical sage.

Jung, however, takes offense at the idea. I suppose, his own ego castle remained animate and alive not the least thanks to his many followers and the circus that surrounded him. One cannot expect the great sage to abandon his own edifice. He only continued building on it, never questioning any part of it. Some of his premises are wrong, however. That’s probably why his dreams emphasized the transcendental element. When he is levitating in space above India (in whose philosophy he rejects the element of self-abandonment) he meets a meditating Hindu sitting silently in lotus posture. He was about to enter his temple when he was called back to life (Jung, 1989, pp. 289-94). In the dream about kneeling before the highest presence (ibid. pp. 217-20), he enters a circular room with

two persons of eminence, the worldly-minded Akbar and the heavenly-minded general Uriah (who had been murdered by — guess who?), to whom he bows down in deference. Arguably, Jung’s ego is comparable to the ambivalent King David, who conspired to kill general Uriah (2 Samuel 11:15).

The spirit is,

prima facie, the greatest

passion of humanity, arguably stronger than sexuality.

From a traditional point of

view, individuation is the purpose of life, and it is not merely

“a prescribed path”. In the early 1980s,

M-L von Franz withdrew from teaching

at the Zurich Institute on the grounds that not enough attention was

being paid to individuation as an unconscious process (cf. Kirsch, 2000, p. 26).

Should individuation come to a halt, then personality is spiritually dead.

It seems that we can detect that people are dead in the way they are

lacking in “love” as a

foundational passion for existence. Lacking a sense of

mystery, they have no longing for the mercurial spirit that is flowing

like a silvery stream behind the veil of existence. Neville Symington (1993) says that, with such people, the “life-giver” in the unconscious is become extinguished. It is an overly simplistic notion, but it seems

to accord with Poul Bjerre’s idea of “Death and Renewal” as the central

theme of individuation. They are stuck and cannot invoke

renewal, and thus they are virtually dead. He exemplifies with people who remain virtually dead

throughout life, and seem to have invoked it as a solution.

Individuation as a parallel spiritual path

There is indeed a process of individuation, although not necessarily as Jung

envisaged it. I think of the notion as a process taking place in the

background, as in the building project of the ‘second skyscraper’. It is

a spiritual project running autonomously or semi-autonomously,

to which consciousness adds its support by way of interim measures of

assistance. To accomplish this, it is necessary to dampen the conscious light. The ambivalent

ego is capable of this. It is also how the

alchemists described the process of

circular distillation. Jung,

however, understands the alchemical process in the usual terms of conscious-unconscious

integration, which is questionable.

If the construction of the first skyscraper depends on ‘integration’ so

the second skyscraper must depend on another process. Obviously, the

latter, during which time it is constructed, is not being

assimilated as a psychic content. It must refer to some other

process. As a suitable modern psychological term, I have suggested

‘complementation’. It is

the semi-autonomous process, mentioned above, during which time

something is brewing and taking shape in the unconscious. I hypothesize

that it underlies true individuation as opposed to chimerical and

ambivalent anima life. It coincides in some measure with

esoteric teachings of olden times. Still, we must have recourse to

psychological understanding, to which religious notions are inadequate.

For the psychological process to function harmoniously when

primary wholeness (Henderson’s ‘Primary God Image’) is abandoned, there must already be an alternative wholeness that

may serve as ideal at the point when the stagnant state is broken,

otherwise a change cannot go smoothly. However, psychology’s focus on integration means that the

negation of assimilated content is out of

the question. Jung never discarded anything. Instead, any inconsistent notion is

complemented with its opposite, having the effect that both

opposites are absorbed by consciousness. Although he had a beef with

Christianity, he never abandoned the Christian standpoint. He only

complemented it with its opposite in the form of pagan Neoplatonism — problem solved!

The notion that individuation can mean destruction, in the sense of

breaking out of an old shell, conflicts with the view of the psyche

as a teleological system that is seeking integration. Since the

telos of

the Self is wholeness, it cannot possibly work toward the destruction of

wholeness. Nevertheless, his youthful vision of God destroying the Basel

Cathedral had a profound effect on him (Jung, 1989, pp. 36-39). To understand

the Basel Cathedral as the burden imposed on us by our Christian

heritage isn’t exactly wrong; but it really

signifies the destructive capacity of the Self to obliterate the

“stagnant wholeness”. Thus, it serves as a symbol of the ‘first skyscraper’.

The vision really points to the future into which he projects a

renewal of the Self, wholly in line with the ideal of ego

abandonment.

This is a youthful dream of the man with the previous discussed skyscraper dream.

I was

overlooking town from a ridge and observed the nearby ongoing

construction of two skyscrapers, which both had begun at ground level

below the ridge, perhaps a hundred meters below. But suddenly the leading

construction collapsed. I looked down and saw many dead people. My

friend, standing beside me, hadn’t seen anything of this. It would mean

that I had experienced a vision of the future. It is relevant that both

constructions begin far below the conscious level.

According to this model, individuation continues more or less

autonomously in parallel with ordinary life, ready to take full charge

of life when time is ripe. It is the notion of a

spiritual path that moves ahead, independently of societal success, while the individual is leading an earthly

existence. It would

mean that the process is self-sufficient, since it is unconnected with the

integrative work. The latter only fulfills a function up to a degree,

sufficient for adaptation to life and the assimilation of one’s own

psychological shortcomings. But at a point in time, the continued

assimilation of content and the expansion into secular and social life will

bring no benefits. It will only bring about stagnation, which to Bjerre is the root cause of neurosis. Thus, we

must question psychology’s overarching ideal of an unending progression of

psychic integration. At some point, we must abandon

integration and wholly focus on complementation, which requires a toning

down of consciousness.

Death and rebirth

Jung discusses rebirth symbolism in his paper ‘Concerning Rebirth’ (Jung, 1980b). He adopts the view that ‘natural transformation’ (individuation) accords with a psychological view of rebirth whereas other forms, such as ‘magical procedures’ are historical and sometimes imitative variants. He claims that “all ideas of rebirth” are founded on the natural transformation of personality (cf. p. 130). Thus, he manages to shoehorn all rebirth symbolism into the integrative paradigm. Jung interprets the death experience as the withdrawal from social life by resort to the introverted standpoint, and exemplifies with an old man taking his abode in a cave as a refuge from the noise of the villages, where he is to be incubated and renewed. Inside the cave an encounter with the archetypal universe occurs, which will lead to the assimilation of archetypal content.

Thus, death and rebirth are invariably regarded as transformation symbols. Transformation does not denote a particular moment of transfiguration — it’s a process that serves to approximate the Self by means of integration. But it’s a goal that can never be fully attained, although the transformation process strives to approximate ego and Self to one another. The Self, which functions as an “invisible guru” or “personal guide”, may be “just as one-sided in one way as the ego is in another. And yet the confrontation of the two may give rise to truth and meaning” (p. 131). It is this newly acquired truth and meaning that constitutes rebirth. He interprets alchemical texts to the effect that it is “not a personal transformation, but the transformation of what is mortal in me into what is immortal” (p. 134).

The rebirth experience leads to a relative change of personality; but it’s not the question of transfiguration. In fact, “[the] repristination of the original state is tantamount to attaining once more the freshness of youth” (p. 136). So it is predominantly an

invigorating experience. Thus, it seems that Jung’s notion of rebirth is not, after all, that much different from the religious rituals of rebirth, which served to revitalize the initiand through the invocation of archetypal truths.

The Self symbolically undergoes a complete transfiguration, as in the metamorphosis of the fish into the Khidr (an incarnation of Allah in human form). Yet, the ego must refrain from identifying with the process. Allegedly, it is an archetypal symbol of transformation that is not applicable in real life. Were personality to undergo a corresponding transfiguration it is tantamount to an “identification of ego-consciousness with the self [that] produces an inflation which threatens consciousness with dissolution” (p. 145).

Paradoxically, then, the Self is not viewed as an ideal and a role model for the ego, but as an Other, a “personal guide” with whom one relates in an attempt to restore harmony. In this interpretation, the Self is, after all, not a self-ideal, but is more like a personality who is to be confronted in order to achieve a more balanced standpoint on part of the ego. This is paradoxical, because the Self in Jungian psychology represents also the ideal of completeness and wholeness.

The paradox shows that something isn’t right. If the Self portrays itself as undergoing a thorough transfiguration, it ought to symbolize the future prospects of personality, although it is indeed possible to downgrade it to a therapeutic ritual enactment. Nonetheless, the deity really urges us to follow his calling and not only to ritualize his message. Jesus said, “Destroy this temple, and I will raise it again in three days” (John 2:19). He is to undergo a complete destruction whereupon he will arise from the dead. He also said, “Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me” (Matt. 16:24). Thus, the disciple is expected to undergo a complete transfiguration, too. Jesus was transfigured and not merely “therapeutically invigorated”.

Normally, the tone of voice is sufficient to identify a person, but Jesus’s disciples didn’t recognize him although they kept company on the road to Emmaus (Luke 24). The meaning of this symbol is evident: he had undergone a complete transfiguration. It was not the question of creating a clone.

Symbolization and amplification

The conclusion is that death and rebirth takes a purely symbolic and archetypal meaning, having essentially the same therapeutic aim as religious ritual. The main difference is that the process is now better understood by recourse to modern psychological terms. However, this may damage the healing effect, since consciousness has a way of devitalizing the symbol. The archetype cannot tolerate the stark light of consciousness, but tends to dwindle to a mundane dimension.

The concept of death and renewal is subjected to ‘symbolization’ in Jung. It never occurs to him that it could mean the actual dethronement, partly or wholly, of the extant personality, including its beliefs and fixations. He rejects the notion of transfiguration proper, since the ego shall not be cast off as an old shell, but must continue the work of integration. Symbolization and mythologization may have the effect that a factual and realistic interpretation is foiled.

Amplification is a way of interpreting mythological images in terms of other mythological images. Amplification, correctly used, allows us to better understand the language of dreams. Our unconscious employs ideation and emotion in a mythological way, and thus we may be informed by historical mythology. If the diverse themes of a dream are archetypal, that is, if they conform with characteristic mythological motifs, then amplification is worthwhile. But the archetypes are merely the stage actors of dreams, whereas the overall meaning of the dream typically boils down to personal difficulties and how to make progress in life. The archetypal themes are employed by the dream function to conduct a stage play that will, in the end, boil down to small-scale personal realizations.

This is also true about the impersonal form of archetypal realization. When the gods land in reality they become mundane beings, as exemplified by the pine tree, the narcissus flower, and the poor carpenter’s son. In fact, the dream function will often make use of everyday language and compose a play with words, which is not at all archetypal but more in the way of rebuses. We must first and foremost search to associate the dream content with personal life and old memories rather than with mythological motifs, which risk leading us astray.

M-L von Franz criticizes the unrestrained use of amplification, in the manner of Julius Schwabe and sometimes also Mircea Eliade. “If you start with the world tree, you can easily prove that every mythological motif leads to the world tree in the end” (von Franz, 1996, pp. 9-15). Thus, it is essential that interpretation is rooted in personal emotion and feeling, otherwise understanding will fly off on a tangent. Symbols mustn’t be treated impersonally, as if they were an end in themselves.

This makes me think that also the symbol of ‘death and renewal’ must mean something personal. It’s not merely a symbolic spectacle arranged by the Self wherein only the Self shall undergo transfiguration, in order to promote secondary therapeutic effects in the ego. In fact, a numinous archetype will become manifest in small-scale form in personal life and invoke a radical change of personality. The intellectual person may “transmutate” into an artistic and feeling-oriented individual, in close proximity to insentient nature — the realm of the spirit. Although personality undergoes transfiguration it does not mean that it is being dissolved in unconsciousness. In fact, there is already an auxiliary ego, a higher personality, in the making. It is like changing ships on the high sea, or moving from one skyscraper to the next.

Yet, Jung downplays the theme of death and resurrection as mere therapeutic self-analysis. For him, it is necessary that the egoic structure remains intact. He says that

[psychologically] this means that the transformation has to be described or

felt as happening to the ‘other’ […] This can hardly be accidental, for the great psychic danger which is always connected with individuation, or the development of the self, lies in the identification of ego-consciousness with the self. (CW 9:1, p. 145)

However, a notion of Self undergoing development isn’t easy to reconcile with the notion of the Self as telos.

Jungian theory has no notion of a collateral and autonomous individuation process, pertaining to an auxiliary Self image (Henderson’s Ultimate God Image) — there is only a singular individuation process that depends on a continual assimilation of personality. Thus, destruction and negation can’t be regarded natural aspects of individuation. I conjecture that this is wrong. Interestingly, Sabina Spielrein, a patient and collaborator of Jung’s, wrote an article named ‘Destruction as the Cause of Coming Into Being’ where she argues that “no change can take place without the destruction of the former condition” (JAP 39 (2), 1994). However, she reasons in obsolete Freudian terms of a destructive drive and a drive for coming into being.

The resurrection body

In

Alchemy (1980),

M-L von Franz investigates the central theme of alchemy, namely the fabrication of the ‘resurrection body’ (glorified body) by means of the alchemical procedure of

circular distillation. She connects it with the resurrection of the Osiris in Egyptian religion. Osiris is imprisoned in the coffin, similar to how the Mercurius is imprisoned in the alchemical Vas Hermeticum. The alchemists believed that they were able to accelerate the processes of nature with the aim of creating a new vehicle for the soul — the glorified resurrection body of Christian theology. According to Christian belief, it is the bodily form that we shall assume at the end of the world. It also denotes the body of Christ after his resurrection.

The alchemists believed that they needn’t wait for the end of the world, but that they could cultivate the resurrection “body” by alchemical means, which will grant the artifex eternal longevity. In this faith, they effectively aimed to reproduce the procedures of the ancient Egyptian priests, whose duty it was to provide the Pharaoh with a resurrection body, that is, to transmutate him into Osiris — the immortal one. Whereas it is unlikely that European alchemists had much knowledge about Egyptian religious chemistry, European alchemy has its roots in Egyptian alchemy and the traditions of Hermes Trismegistus — a holy teacher identified with the Egyptian god Thoth, who knew the magic of resurrection.

The physical mummy is equated with the Osiris, and it must be preserved as the carrier of the soul. A person who had gone through the rituals of resurrection “would be able, as the papyri texts say, to appear in any shape any day. That meant the dead could leave the coffin chamber; they could leave the tomb of the pyramid and walk about in the daylight and could change shape. They could appear as a crocodile and lie about in the sun by the Nile, or they could fly about as an ibis” (von Franz, 1980, p. 236).

According to this belief, the old body shall be cast off as an old shell and the soul shall continue to live in a new body. Since the egoic framework in psychology cannot be discarded but only complemented with yet more psychic content, it’s not worthwhile to interpret this symbol in traditional psychological terms. Of course, von Franz realizes this, and that’s why she gravitates toward a religious interpretation, on lines of the ancient Egyptians, i.e. that it signifies the “incorruptible essence in man which would survive death”. The Self contains the “divine nucleus in man which is immortal”. She says that “[it] is an experience of something immortal lasting beyond physical death. You know that in parapsychological reports this is also sometimes mentioned as a typical quality of the soul of a dying person” (ibid.).

Von Franz’s parapsychological interpretation is, of course, accompanied by a traditional symbolical understanding; but it is evident that theory is ill-equipped to interpret the central alchemical mystery, since there is no way that it allows for the destruction of the old form of earthly personality. In fact, the symbol of the resurrection body means that our personality is to be totally renovated. Self No. 1 is abandoned for Self No. 2, capable of living in unison with earthly reality. No. 2, has acquired earthly transcendence and is truly experiencing life‘s presence. He may take to flight with the ibises, or lie about with the crocodiles, because the Kingdom is present in every direction. Personality No. 2 will slowly take shape under the auspices of personality No. 1, who has decided to contribute to its growth in the unconscious vessel. The resurrection body has many names: filius philosophorum, filius regis, infans solaris, Adam Kadmon, among others. Jung says about him:

And yet that light or ‘filius philosophorum’ was openly named the greatest and most victorious of all lights, and set alongside Christ as the Saviour and Preserver of the world! Whereas in Christ God himself became man, the filius philosophorum was extracted from matter by human art, and by means of the opus, made into a new light-bringer. In the former case the miracle of man’s salvation is accomplished by God; in the latter, the salvation or transfiguration of the universe is brought about by the mind of man — “Deo concedente,” as the authors never fail to add. Man takes the place of the Creator. (Jung, 1983, p. 127)

Note that he takes the view that it concerns the “transfiguration of the universe” whereas it is really about the apotheosis of the artifex. He then goes on to explain that it forebodes the rise of science, which would change the world and let man take the place of God. But this has nothing to do with it. He makes again the reductionistic interpretation that so many have done before him. He understands it as changes going on in the collective unconscious, which will impact the collective ways of mankind. Thus, the transformations of the Self are relevant to the ego only in a limited sense, and the latter should refrain from identifying with them. His understanding again focuses on integration, now ready to produce the scientific mindset. This runs counter to the view of the alchemists who saw it as a way of personal salvation. Gerhard Dorn, Jung’s favourite philosopher, worked to achieve the ‘unio corporalis’, which represents the unification of the ‘unio mentalis’ with the previously mortified body. The work of self-redemption runs like a red thread throughout the history of alchemy, even from its beginnings in the 1st millennium B.C. The “body” shall undergo transmutation; but it is not about the salvation of the world. (The Christ has taken care of that.) It really means that the artifex searches to acquire the glorified body in advance and in this manner to redeem himself.

Jesus isn’t lying when he presents the mystery of resurrection as something that is open for everyone, and not only relevant for the Pharaoh of Egypt. Nor does it refer to a life in the hereafter, because people can possess life “here and now” as well as in eternity, for they have “passed from death to life” (John). “You won’t be able to say, ‘Here it is!’ or ‘It’s over there!’ For the kingdom of God is already among you” (Luke 17). When Jesus rises from the dead, he is transformed and may take up his place at the right hand of the Father. It means that he is back in the paradisal Eden, together with God. “When you come to know yourselves, then you will become known, and you will realize that it is you who are the sons of the living father” (Thomas 3). Thus, we can all attain the heavenly kingdom, provided that we are capable of abandoning our personality No. 1, which has served its purpose insofar as it has provided us with a worldly-minded and realistic attitude. Although it has been of help in the adaptation to harsh reality, it also constitutes a prison for the soul.

Therapeutic ritual

In Jung’s terms, this is an archetypal symbol that cannot take effect in the ego, but must only be applied ritually, however in the modern way of active imagination. Instead of partaking in institutionalized ritual, the mind can forge imitative fantasies of its own, an activity which is believed to have a similar therapeutic effect as religious ritual.

M-L von Franz tries to remedy Jung’s symbolistic reductionism by recourse to parapsychology whereas James Hillman regresses to the neurotic solution of extraverted romanticism. It is time to realize how conservative Jung is about the life of the soul and how he notoriously applies symbolistic reductionism and the paradigm of integration to reduce mystical transcendence to therapeutic exercise. People always think about Jung as the liberator of the soul, although he is something of an archconservative stick-in-the-mud. He is equally conservative about the “terrifying” reality of the archetypes as Freud about sexuality.

When the spiritual mystery finally lands in reality, it does not mean that one has acquired the ability to walk through walls, like the Osiris. It would mean that worldly-minded and ambivalent personality has been cast off, allowing room for the divinely inspired person whose heart is open to the Kingdom of God, which has always been nigh. The personality No. 1 is only provisional. I dreamt about this very theme recently.

At a sunny day I was making an excursion into a beautiful area for open-air activities. However, I immediately chose to climb a big mountain from where I had a good view. But I couldn’t find a way down, so I had to go back. It was then that I found out that it was fake. It was made of some plastic material that had been masked with a cloth which made it look very natural. I knocked on it and it sounded plastic and hollow. I slid down the mountain at good speed, sitting on my back. It impressed an old gentleman passer-by. From below, it was impossible to see that it was a fake mountain. I ventured out in the natural surroundings and was slightly surprised to see that many people were living here in big apartment buildings. There were small industries, too. It looked like a very harmonious area, close to nature. I wended my way into the attractive surroundings.

This is an apt example of how the dream function supports the already accepted standpoint rather than compensating it. The fake mountain is provisional personality No. 1, which is abandoned with great ease. The “heavenly kingdom” which I venture into is a very normal and civilized world, and not a fairytale paradise with supernatural creatures. It is an ‘outline dream’, which strengthens the resolve to abandon the plastic mountain. Although the mountain was a nice and cleanly place with a good overview, life there has been unconnected with reality in the profound sense. There is no need for the intervention of a giant that crushes the first skyscraper, because I’ve already made up my mind. That’s why the process is portrayed as so much easier. The manner in which I slide down the mountain (when the old man commended my bravado) portrays the process as “child’s play”, which is a well-known saying in alchemy: the ‘ludus puerorum’. The rest is easy. Just let nature take over, and don’t hold fast to anything. Jung finds no explanation for this idea. He thinks it is euphemistic (cf. Jung, 1980, p. 199).

On Jung’s view, this is the plastic ego mountain on which one must settle permanently and resort to therapeutic measures to make life bearable. But the abandonment of the plastic mountain is the objective of the alchemical opus and the goal of Jesus’s rebirth mystery. It’s no wonder that the filius philosophorum is so long in the making, because the artifex must, in a manner of saying, learn to play the celestial violin. Jung’s understanding of the alchemical and Christian mystery leaves something to wish for. It is reductionistic, in a sense.

In his otherwise erudite and rewarding works he manages to shoehorn his notion of individuation, as consecutive phases of integration, into the concepts of spiritual tradition, such as yoga. As a consequence it comes to be regarded as a therapeutic measure for the stagnant ego, rather than a means of transformation proper. A misinterpretation of mystical tradition, such as alchemy, is not to be taken lightly because it devaluates the precious symbols and it leads the seeker astray.

Hegelian collective individuation

I highlighted the way in which Jung interprets the filius philosophorum as the harbinger of science. He is thinking especially about Jungian psychology. He saw alchemy as proto-psychology, i.e., he projected the tenets of his psychology on alchemy. Thus, the filius philosophorum represents not only material science but psychological science, especially. This newborn spirit is bound to redeem the world, by imbuing it in a new light, thus replacing the light of the Christ. This thinking is known as the Hegelian unfoldment of the World Spirit, which aspires to yet higher and higher levels of consciousness.

Jung believed that the World Spirit is brewing in the unconscious, and that alchemy represents this very brewing process. Of course, the truth in the matter is that science ran apace when the straightjacket of theology was finally removed. Every historian of science knows this. Science has been there all the time, at least since the time of Aristotle. By example, scholars of medieval times believed that Adam’s atoms had propagated and are now continuing in our bodies. This served to explain the theological dogma of the propagation of original sin. We are of the same substance as Adam’s body — so they believed. Thus, the food we eat does not contribute to the building of our bodies. We are in fact only extracting the energy from the food. But when scholars no longer needed to heed to theological dogma, they began to think freely.

The final blow to the Catholic church came with the theologically inexplicable Lisbon earthquake in 1755, after which the floodgate of science and rationality was released. Science and rationality had only been held back, because it had been there all the time. Thus, science did not jump out of the collective unconscious as if the scientific mindset hadn’t existed before. It is true that the expansion of consciousness depends on the unfolding of the unconscious, and that ideas are always brewing in the vessel. But the notion that alchemy and its symbols represents proto-science, serving to prepare us for the scientific and psychological mindset, doesn’t hold water. It is a Hegelian and unscientific fantasy; the belief that we are guided by an unconscious Will that continually unfolds in reality.

As a matter of fact, alchemy already incorporated chemical science, and alchemists were already making important discoveries. They had recourse to all the chemicals and equipment, still in use. But it was only at the point when mystical theology was stripped from it that chemistry began to unfold. Chemistry was already present, but clad in mystical language. Thus, alchemy represents the path of transcendence. Alchemical fantasy was a form of creativity, an art of imagination, that served to gather the celestial sparks in creation. Jung sees the Opus as constituting a heap of naive projections on matter, a project doomed to failure, since they could never manage to integrate their findings as psychological insight (perhaps with the exception of Dorneus, according to Jung).

In fact, the alchemical Opus did not serve the end of integration — it was a form of

complementation. Many an artist and musician is devoted to the same process. A modern painter adds chemical compounds, dissolved in linseed oil, to a canvas. The canvas serves the same purpose as the vessel in medieval alchemy. By example, have a look at this painting where Picasso has filled the “canvas egg” with the typically ignoble items in earth colours, characteristic of ‘prima materia’. In alchemy, the vessel is notoriously associated with the egg. It shall give birth to the ‘infans solaris’, the golden child.

“Still Life With Chair Caning”. Pablo Picasso.

The alchemists knew very well what science was; yet they insisted that they were devoted to an holy art form. They did indeed manage to gather the ‘scintillulae’ (Lat. little sparks) from matter. It is a remarkable success story that has prevailed throughout the Christian era and long before. Not many spiritual disciplines have been so fruitful, pervasive, and resilient. It depends on the fact that it did not only revolve around prescribed collective values, ideas and techniques.

Jung did not only project his psychology on the alchemical art. He saw it in Gnosticism, too, despite the fact that it could not be understood in Jungian terms. He also projected psychological tenets on the book of Job. Eventually, he projected them on the universe as a whole, which is said to harbour the archetypes-as-such in a wholly transcendent realm, namely the

unus mundus. In

Answer to Job (1969), Jung portrays the divine drama with Jahve as client. Jahve undergoes psychoanalysis with Job as analyst, and a lot of transference and countertransference takes place.

I believe it is a grave misinterpretation. The biblical Wisdom books (including Wisdom of Solomon) give expression to a longing after the Sophia (Wisdom) — Sapientia Dei. According to Jung, this shows that Jahve longed to become conscious, because wisdom relates to consciousness. But Sophia really denotes the fallen heavenly being responsible for the orderliness of the world, whose ‘scintillae’ (divine sparks) the Gnostics and the alchemists endeavoured to gather for the subsequent transportation back to the celestial sphere. Thus, contrary to Jung’s belief, the salvation of Sophia signifies the opposite movement than the descending movement of incarnation.

The soul-spark

The scintillae of matter are the heavenly atoms that, when gathered, constitute and replenish the resurrection body. Eventually, the filius philosophorum shall rise from the receptacle. Thus, the alchemist redeems himself, but he also redeems God, who is longing after spiritual replenishment due to his great sacrifice. He is longing after Sophia. So the movement goes in the opposite direction than that of assimilation, which is why Jung could never arrive at a proper understanding of Gnosticism and alchemy. To him, the scintillae in matter represent archetypes that must be integrated. But it doesn’t make sense to interpret the divine restoration of the scintillae as conscious integration, for human consciousness cannot be equated with the heavenly abode where cosmos had its beginnings. In my article ‘Complementation in Psychology’ (

here) I point out in what ways ‘Answer to Job’ is defective.

The filius philosophorum represents the resurrection body. It shall serve as the new vehicle for personality, after Self No. 1 has been cast off. The Opus does not serve the Hegelian purpose of integrating God with terrestrial existence in yet more revelations of consciousness. In fact, it wins back to God that which has been lost to him due to his continual unfolding in the world. After having acquired the resurrection body, which is the heavenly person, the stark light of consciousness is dampened, and the disciple’s eyes are opened to heavenly things that were imperceptible before. The stark conscious light has hitherto blinded him to the faint spiritual energies. He will be able to discern the soul-sparks that permeate reality, and may continue to gather the heavenly food, a feat that could only be achieved with difficulty before.

Arguably, it is not a sudden conversion of personality, but more of a slow descent to a true life, as opposed to the alienated existence upon the plastic mountain. By way of the artful gathering of the scintillae, the Christchild grows heavier all the time, as in the legend of Christopherus (cf. Wiki, Saint Christopher,

here). Thus, the conversion to a new person should probably be seen as a continual process, where the transfiguration to a new body serves as symbol for the moment when the decision is taken to abandon the earthbound ways, no longer to endorse the ways of the integrative paradigm and the diverse forms of personal advancement. It would correspond to the very moment when the Christopherus of legend places the Christchild on his shoulder and steps into the water. This is child’s play, “[for] my yoke is easy and my burden is light”, says the Christ (Matt. 11:30).

The spiritual pilgrim may loosen the grip and slide down the plastic mountain, because he/she has learnt how to gather the celestial sparks by recourse to the art. After that moment, to slide down is a ‘ludus puerorum’. Thus, the abandonment of personality No. 1 is not a metaphysical event, but would represent the moment when the pilgrim makes up his mind. At this precious moment the transfiguration process catches up speed, and it cannot be stopped. It is like sliding down a mountain with the aid of the natural force of gravity.

This is the correct interpretation of alchemy, which runs counter to Jung’s Hegelian reading, building on the paradigm of integration. The tribulation of Job, as well as the sacrificial work of the Gnostics and alchemists, really belong to the parallel paradigm of complementation.

Conscious expansion as evil

On a moonlit night we may see many things that we couldn’t see before, when we had recourse only to our analytical consciousness that separates all things. In the moonlight, things tend to meld together to reveal their sublime nature. Where we only saw distinct things before, they now meld with the surrounding to reveal the presence of an ethereal reality.

It is the cooperation of the sun and the rain clouds that makes life possible. The unconscious is like a cloud that provides us with life-giving moisture, without which sentient life couldn‘t exist. The moist principle serves to dampen the conscious light to the furtherance of the sacred. It is divinely procreative while sustaining a standpoint of quiescence. But the unconscious is not a horn of plenty capable of providing for us perpetually. The principle of integration has yielded an unbalanced view of the psyche.

Nor can we expect that God (or the World Spirit) will incessantly provide us with the boons of a continuous incarnation. The Gnostics saw the incarnation of Sophia as a monumental divestiture of celestial life, and it was incumbent upon mankind to settle the accounts. We must pay back what we owe the celestial Father by working for the salvation of Sophia, which is the spirit imprisoned in the world.

Christian theology, as opposed to Gnostic theology, focuses on the boons of incarnation, an overly one-sided standpoint which is continued in psychology’s focus on integration. But the spirit has already given up its autonomy to an enormous degree and we cannot expect conscious expansion to continue interminably. Divine autonomy must be restored. The Hegelian project of Jung’s has run up against a brick wall on account of one-sidedness. That’s why his theory of the transcendent function doesn’t work. It is supposed to serve as a pipeline for the transportation of goods of the unconscious, but it cannot contribute more as it will ruin the balance. The moon sap, which in myth rains down on earth during the moon’s waning phases, is dwindling. Life cannot continue without it. What remains is a sun-scorched earth, where the ego abides upon the plastic mountain, entertaining its dried out archetypal concepts.

There is in theory only a flux from the archetypal to the temporal sphere, but there is no notion of a flux in the opposite direction. Thus, Jungian psychology is very much a child of its times. What does it help to remain aware of the repression of the feminine in our culture when there is no means of remedying the problem, other than to proselytize and make more people aware of the fact? As a consequence, even more people will have been recruited to an inadequate standpoint. It is a way of pretence, an aloofness from reality, which only serves a personal therapeutic end, since it enables the person to sustain his faith and steadfastly remain in the foxhole. Yet it represents stagnation, an artificial life made permanent with the aid of a clever ploy of consciousness.

Active imagination may serve as an artifice by which new tokens of worship are created, in lieu of the Christian. It is the fast-food variant of pagan worship, in a sense. But in that case it serves only a therapeutic purpose and leads nowhere. It is high time for Jungians to learn something from the Christian mystics, who Jung rejected off-hand. The

nigredo of the alchemists, and the ‘dark night of the soul’ of the mystics, does not signify the encounter with archetypal content, nor with the ambitious goal of extorting even more treasures from the unconscious.

In fact, the nigredo represents the abandonment of the “Happy Neurotic Island” and the opening of our senses to the faint fragrance of the sacred, ever radiating from the Sophia of the Gnostics, or the Mercurius of the alchemists. The faint stars in the darkness will continue to multiply, leading to the

albedo — the morning of a new life. It is a great moment when the grand building collapses, leaving only a naked island in its stead. Soon the rock will be covered with sparse and thin grasses. The return of life has begun, which is a precious moment. As Bjerre predicted, stagnation always ensues. There is only one way out of it, namely “death and renewal”.

The God-man

The manner in which the divine promotes new temporal life and how it offers itself up for us, is a mystery that is portrayed in the religions of the world, especially pagan religion. The gods sacrifice themselves for the benefit of humanity, as in the Passion of Christ. The deities are culture heroes, which means that the hero archetype is involved. It is also the central theme of fairytales. Narcissus sacrifices himself, too. The god-man remains the pre-eminent symbol of the complementarity in our nature.

The god-man of pagan religion poses a quandary to the

theologians. According to some theologians (e.g. Bultmann, Barth,

Kaufman) the “Christ event” is always ‘in potentia’, while it also

manifests continually. In the beginning of the Christian era, it

“spilled over” from myth into reality. The pagan myths confirm that the

Christian myth is deeply rooted in human psychology, and that people had

for centuries longed for the Christian revelation at the time of its

advent. To the Celts and the Teutons, the story of the suffering king

whose death brings blessing upon humanity, who hangs upon a tree

penetrated by a spear, was nothing new. The druids used to lop a tree

into T-shape form, as a symbol of the sacrificial king. The Graeco-Roman

versions of Jesus, however, weren’t real enough. They had this fairytale

character typical of Graeco-Roman religion. Greek culture had a penchant

for the abstract, as typified by the Greek philosophers, including

Plato. Jewish culture, however, was more oriented towards concrete

realization, not to philosophize but to make things manifest.

Quite possibly, the Australian aborigine story of the god-man is quite

ancient. Who knows, it could be many thousand years old. The myth

of “The Southern Cross” is about the first humans, two men and a woman,

who ate only plants. One day during a famine, the woman and one of the men

broke the rule of the sky king and killed a kangaroo rat. The other man

would not eat but walked angrily away towards the sunset. He continued

to walk until he fell down dead under a white gum tree. The death spirit

Yowi appeared and put him in the hollow centre of the tree. A terrific

burst of thunder was heard and the gum tree lifted from the earth

towards the southern sky where it planted itself where the Southern

Cross is now seen. The constellation looks like a Christian cross. It is

the smallest yet one of the most distinctive of all the modern

constellations. In the southern hemisphere, the Southern Cross is

frequently used for navigation (cf. Langloh Parker, pp. 9f).

Thus, to the aborigines, the cross is the symbol of the original man who

is faithful to God, whereas the other two correspond to Adam and Eve who

fell through sin. The god-man’s sacrifice follows upon the arrival of

sin in the world. He is buried in the tree, whereas the Christ was

fastened on the tree. Both symbols express the unity of the god-man with

the cross.

Among Indians of Central America there existed a god-man called the

‘bird-serpent’ (Quetzalcoatl, Kukulkan, Kukumatz) who, according to the

Toltecs, preached flower-offerings instead of human offerings.

Remarkably, in Toltec myth he appears as a white man with a beard. When

the conquistadors arrived in the Aztec kingdom there were crosses

erected to his honour. The vertical and horizontal axes of the cross

would signify the heavenly and the earthly natures that are united in

him. The fact that he is a bird as well as a serpent also points to his

double-nature.

Like Jesus he was chaste. In the manner of Jesus, he surrounded himself