Abstract : The theory of four disunited psychic functions is critiqued. In accordance with Augustine’s theory of the Trinity as the prototype for the human soul, a unitive triadic structure is proposed. Intuition is not a separate psychic function. It is a triadic synthesis that brings wholeness of self and unity of consciousness.

Keywords : triadic psychic structure, intuition, feeling, wholeness, trinity, C. G. Jung, St Augustine, Mark Solms.

Carl Jung’s Psychological Types, published in 1921, is reckoned among his finest works. However, since then, much research has been done in the field. It is high time for a thorough overhaul of his theory. Jung proposes a model of four independent psychic functions: thinking, feeling, sensation and intuition. Thinking and feeling stand in a compensatory relation, and the same is true for sensation and intuition. The model is a quaternity of opposites:

Fig. 1. The quaternary model.

The primary function can be any of the four. It is here illustrated as the uppermost and most conscious function in the conscious-unconscious gradient. The compensatory relation between opposite functions means that they are involved in a balancing act. A too dominant thinking function will be interrupted by feelings from the unconscious, because the feeling function of the thinking type is unconscious. The thinking type suppresses feeling, “for nothing is more liable to prejudice and falsify thinking than feeling values” (CW 6, para. 600). Analogously, the feeling type suppresses thinking, for “[n]othing disturbs feeling so much as thinking” (ibid. para. 598). The corresponding suppression of the ‘inferior function’ is present also in the other types. The contrariness of thinking and feeling seems to be a Western cultural idiom that refuses to go away. Says Jung:

The discrepancy between intellect and feeling, which get in each other’s way at the best of times, is a particularly painful chapter in the history of the human psyche. (Jung, CW 10, para. 569)

But what Jung is referring to is the moment when a certain feeling has a disturbing effect. It is not true for feelings in general. After all, we often observe how naive thoughts are accompanied by infantile feelings and sophisticated thoughts by mature feelings. Yet, in many a 20th century textbook intelligence is connected with the absence of feeling: Emotion contains no “trace of conscious purpose”; it causes “complete loss of cerebral control” and an “acute disturbance of the individual as a whole” (as referenced in Feldman Barrett & Salovey, 2002, p. xii). The neuroscientist Antonio Damasio calls this the “high-reason” view:

The “high-reason” view, which is none other than the common-sense view, assumes that when we are at our decision-making best, we are the pride and joy of Plato, Descartes and Kant. Formal logic will, by itself, get us to the best available solution for any problem. An important aspect of the rationalist conception is that to obtain the best results, emotions must be kept out. Rational processing must be unencumbered by passion. (Damasio, 1994, p. 171)

Damasio explains that this cannot work, because we would get lost in the byways of our calculation. The enormous tree of imaginary scenarios that the process of logical inference gives rise to must be radically pruned. This is what feeling does. Because the feeling is about the body and because it “marks” an image, Damasio calls it a somatic marker.

It forces attention on the negative outcome to which a given action may lead, and functions as an automated alarm signal which says: Beware of danger ahead if you choose the option which leads to this outcome. The signal may lead you to reject, immediately, the negative course of action and thus make you choose among other alternatives. The automated signal protects you against future losses, without further ado, and then allows you to choose from among fewer alternatives. […] When a positive somatic marker is juxtaposed instead, it becomes a beacon of incentive. […] Somatic markers do not deliberate for us. They assist the deliberation by highlighting some options (either dangerous or favorable), and eliminating them rapidly from subsequent consideration. (ibid. pp. 173-74)

As an avid chess player I’m well aware of this. When calculating a line that leads to a negative outcome I get scared. This is odd. After all, it’s not like I’m hanging on a cliff. Correspondingly, when investigating a line with a positive outcome I get elated. This is kind of silly, too; but this is how the mind works. It is required in order to accelerate the process of decision-making and to find the necessary emotional motivation. A gambling addict is well aware, intellectually, that statistics are against him. However, since he is not scared of the consequences he cannot break free of the addiction. On the other hand, the feeling response can be too strong. I know for a fact that a person with a nervous disposition can get a recommendation from his doctor to stop playing chess, because it is too nerve-wrecking to calculate variations! The conclusion is that an effective thought-process requires levelheaded feeling. Already Wilhelm Wundt found that “the clear apperception of ideas in acts of cognition and recognition is always preceded by special feelings” (Wundt, 1907, p. 436). Psychologist Robert Zajonc says:

In nearly all cases, however, feeling is not free of thought, nor is thought free of feelings. Considerable cognitive activity most often accompanies affect, and Schachter and Singer (1962) consider it a necessary factor of the emotional experience. Thoughts enter feelings at various stages of the affective sequence, and the converse is true for cognitions. (Zajonc, 1980)

Feeling accompanies all cognitions, says Zajonc (ibid.). It means that thought and feeling are compatible. In fact, “consciousness is feeling”, says neuropsychologist Mark Solms (2002, ch. 3), or more precisely, “feeling is the foundational form of consciousness, its prerequisite” (Solms, 2021, p. 265). It’s because “[t]he structures that form the core of the emotion-generating systems of the brain are identical to those that generate the background state of consciousness” (Solms & Turnbull, 2002, ch. 4). The authors further explain that

“[c]ore consciousness” relates information about the current state of the self to the prevailing circumstances in the outside world — the source of all the objects that the self requires to meet its inner needs. This information is conscious because it is intrinsically evaluative; it tells us how we feel about things. This applies especially to the inwardly derived aspect of consciousness — the conscious “state” — which provides our background sense of awareness. This background sense of awareness is not merely quantitative; it always has a particular qualitative “feel” to it. Conscious awareness is therefore grounded in emotional awareness. (ibid.)

Thinking, explains Solms, may be regarded as imaginary acting, whereby the outcome of a potential action is evaluated by feeling, while the motor output of the envisaged action is inhibited:

Freud refers to thinking as ‘experimental action’ (i.e. virtual or imaginary action). In contemporary neuropsychology, this is called ‘working memory’. Working memory is conscious by definition. (Not all cognition is conscious; but here we are concerned only with conscious cognition.) The function of working memory is to ‘feel your way through’ a problem until you find a solution. The feeling tells you how you are doing within the biological scale of values described above, which determines when you have hit upon a good solution… (Solms, 2016, p. 28)

Thus, we feel our way through a virtual reality of thought:

We must remember that thoughts are just an internalized version of our perceptual experiences of the world. All thoughts, as distinct from feelings, have a perceptual format that is derived from sensory images. […] So when we are feeling our way through a problem using thoughts, we are, as it were, feeling our way through a virtual form of reality, feeling our way through representations of reality. The function of thinking, in this sense, stands for reality. It’s a virtual space in which we can work out, in the safety of our minds, what to do in relation to reality, before we actually put solutions into effect. In short: thoughts are interposed between feelings and actions. (Solms, 2015)

Psychoanalyst Marianne Leuzinger-Bohleber says:

Psychic processes, such as “unconscious memories” or affects and fantasies evoked in a certain situation are “constructed” between subject and environment in the here and now of a current interaction: consequently, thinking, feeling and action thus arise only interactively: the subject cannot learn in an insular quasi autistic capsule and further develop itself: it requires interaction with the environment. (Leuzinger-Bohleber, 2016, p. 145)

Thinking, feeling and sensation are in constant interaction. Thinking does not take place in an autistic capsule, since it is dependent on the other functions for its operation. The upshot is that the theory of stand-alone psychic functions must be abandoned. According to Jung’s quaternary model, opposite functions are antagonistic. This view is at variance with our experience of consciousness as a single integrated state — the unity of consciousness. Jung’s solution to this is that “compensation is an unconscious process” (CW 6, para. 695). Yet, it seems far-fetched that we should be totally oblivious to this continual balancing act.

Anyway, it’s clear that compensation requires that the inferior function stays unconscious, in order to serve as a bridge to the unconscious (cf. CW 18, para. 212). Curiously, a thinking person must not differentiate his conscious feelings, in preference for intrusions of primitive unconscious feelings. It seems to contradict Jung’s goal of the relative integration of personality, supposedly leading to an approximation to the Self; the archetype of psychic wholeness. After all, full integration of personality requires “the union of the four basic functions” (CW 14, para. 390). Regardless of contradictory theory, how can compensation occur unknowingly between the two ‘auxiliary functions’, which are not suppressed?

Jung always thinks in opposites. It is sometimes worthwhile, but not always! Opposites must belong to the same category. Electrons and positrons are opposites because they belong to the lepton type of elementary particles. They annihilate each other if they meet. Analogously, Jung places feeling and thinking in a category called “rational functions” (CW 6, para. 787). When something is put in the wrong category it is called a category error. As we’ve seen, thinking provides a virtual reality experienced and evaluated by feeling. Thus, thinking and feeling are very different in their nature and are therefore not conflicting. Category errors result from thinking too much in terms of opposites. The Gnostics thought of the soul as a “spiritual body” held captive by the physical body from which it must emancipate itself. A category error made them think that the spiritual body was in perpetual conflict with the physical body. In fact, they are a wholeness, as Augustine explains, because the mind belongs to a different category than the body. It is higher up on the ladder of being.

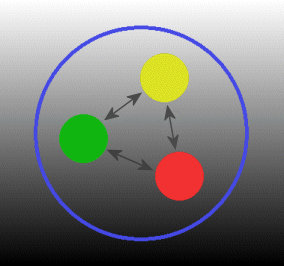

Thinking in opposites is attractive, probably because it is diagrammatic and appeals to the orderly and rational left hemisphere. It lends itself to thinking in quaternary structures, such as Jung’s psychic model (fig. 1), whose structure is two-dimensional rather than only one-dimensional, which makes it doubly dualistic. The triadic model is anathema to dualistic thinking, because a trinity cannot consist of opposites. It can only be a dynamic wholeness of cooperating elements. Curiously, Jung often quoted the axiom of Maria Prophetissa: “One becomes two, two becomes three, and out of the third comes the One as the fourth.” This “enigmatic” axiom, as he says, “presumably means, when the third produces the fourth it at once produces unity” (CW 9i, para. 430). This is in fact a trinitarian formula. It is dynamic; as the numbers commute, they are not in opposition. In this three-unity the One is equal to the fourth, as in fig. 2. Yet, there is no fourth element. The One emerges from the three elements as epiphenomenal unity, the blue circle in the image. As it consists only of three elements, it gives the lie to the quaternary model, and that’s perhaps why the axiom remained in the back of his head as a gnawing doubt.

The next big fish to fry is intuition. Jung defines it as “perception via the unconscious” (CW 6, para. 951). In the plentiful literature on intuition it is most often defined as a multifarious phenomenon that conveys “immediate insight”. There is moral intuition, aesthetic intuition, intellectual intuition, divine intuition, etc. Since intuition has also a cognitive aspect it can hardly be categorized as perception simply. I propose instead that intuition is what underlies the unity of consciousness, through the joint operation of the three psychic functions; thinking, feeling and sensation. The whole is more than the sum of the parts, and that’s why intuition can be seen as an emergent form of consciousness. The subject habitually employs the favourite psychic function; but when consciousness relaxes, the other two functions can join in on equal terms. It results in intuitive insight. The following improved model illustrates the triad of interdependent psychic functions. They give rise to intuition (the blue circle) as epiphenomenal mental unity.

Fig. 2. The triadic model.

In De Trinitate, St Augustine proposes several triadic structures of the psyche. By psychological analogy he wants to apply the doctrine of the Trinity to the structure of the human mind. Science has verified Augustine’s hypothesis that the innermost structure of matter is in some measure analogous with the Trinity. Thus, the quarks in stable matter are structured exactly according to fig. 2. (cf. Winther, 2019, para. 5). Augustine is probably right about psychic structure, too. He aims to describe triads of functions that belong together since they are really a unity. He proposes triads such as memory + understanding + love, or memory + inner vision + will, and so forth. However, he is not quite satisfied with the result, for in the epilogue he confesses “that the wonderful knowledge of Him is too great for me, and [I] cannot attain to it” (De Trin., XV: 50).

Augustine wants to show how we can attain an earthly proximate to the divine life according to the trinitarian analogue in the mind. Since we are a fallen species, mired in sin, we can never come to grasp the Trinity, nor can we ever attain true mystic union with God. Rather, with recourse to the faith, we must work to repair the inner image of the Trinity. Our capacity of intuition can be trained, and much literature is devoted to the subject. The angelic intellect, says St Thomas Aquinas, “understands the truth of intelligible objects not discursively, but by simple intuition” (Summa Theologica, part I, Q58:2). Thus, the disciple can come closer to fullness of being by the recovery of the angelic faculty of the mind. It is an antidote for the earthly pessimism of the Augustinian theological project. The model that is presented here is what Augustine sought to find; but he had not the modern concept of intuition, only the Aristotelian.

Avicenna (c. 980-1037) and al-Ghazali (c. 1056–1111) connect prophesy with intuition and regard it as the highest expression of the human intellect. Avicenna calls intuition the “sacred faculty” or the

“sacred spirit” (Treiger, p. 77). However, since intuitive prophesy is continuous with the normal activity of the human intellect it is not equal to divine spirit. It is “the most luminous and purest part of the cogitative spirit” (ibid. p. 75).

Prophets are endowed with a superior intuition. Their mode of cognition is called inspiration and

revelation. Alexander Treiger says:

We can see that, according to Avicenna, the soul can derive knowledge from the supernal realm. As has been pointed out by Dimitri Gutas, on the basis of this and other texts, this knowledge is twofold, incorporating, on the one hand, intelligible universal concepts, found “in the Creator’s and the intellectual angels’ knowledge,” and on the other hand, forms of the particulars, i.e. past, present, and future individuals and events, generated, and hence also thought, by the souls of the celestial spheres (called here “the souls of the celestial angels”). […] Finally, Avicenna indicates that in order for the connection to the supernal realm to occur, the imagination must be as free as possible from distractions from both the sense and the intellect. (ibid. pp. 79-80)

Notably, Avicenna, unlike al-Ghazali, puts emphasis on imagination as essential for the strong intuition characteristic of profethood. Nigel and Maggie Percy are devoted intuitives of the present era. They find that intuition consists “of information accessed by a variety of channels or modes, making a simplistic single explanation no longer acceptable” (Percy, 2019, ch. 15). They argue that intuition is underestimated in the modern time:

The perception and awareness of intuition can be improved, most simply by becoming aware of its existence. And the fact that it can be trained to be something larger and more obviously a part of our lives gives credence to the existence of a base level, if you will, of some natural force at work within us. […] [T]hat wonderful experience of consciousness above and beyond our senses brings to us that which we need to make our lives richer and fuller, deeper and more meaningful. That undercurrent of consciousness creates those moments, those intuitions or phenomena, which our senses are then able to perceive, but it does so by virtue of the nature of the web of life itself. As we live, we pull on strands of that web, and those tugs and movements are felt and come back to us as intuitions. It is for these reasons that intuition, I believe, is always at work every moment of every day. It cannot be otherwise, given its nature. This ever-present aspect of it is important to remember, just as it is important to remember that we cannot escape it. […]

Something which medieval minds knew for certain is something we have forgotten. The universe may appear to be remote and uncaring, but it is not, and intuition is the way it shows that it both listens to us and responds. Intuition is, therefore, our greatest gift, transcending as it does time and space, giving us access to untold amounts of information beyond the reach of our senses and reminding us, if we let it, that we consist of far more than we allow ourselves to think. (ibid.)

In order to be “as free as possible from distractions” it is necessary to follow the example of Augustine, as explicated in De Trinitate and Confessiones (Book X), where he turns inward to recover his “memories”. Augustine sees this as a clean-out of the “spacious palaces of memory” in order to create space for the Truth that comes from God through divine illumination. He has especial focus on his sinfulness of yonder days. Today, self-analysis is understood as a methodical attempt to study and comprehend one’s own personality or emotions. The central tenet of psychoanalysis is that unconscious complexes may disturb consciousness. It is remedied by the assimilation of unconscious content.

Thus, Augustine’s project could be understood as the cleaning of the window of the soul which is intuition. Wholeness is not achieved solely by the integration of the unconscious. It is a preparatory stage that will allow the three psychic functions to sing in unison. In Augustine’s view, any union, such as the union of body and soul, has greater scope than any of its constituent parts. Thus, any two-unity or three-unity is closer to the fullness of Being, which is God. Although mankind is disjoined from God, we have recourse to an earthly analogue of the divine trinitarian mind.

This is how we must understand intuition. It is always active, as it underlies our unity of consciousness; but it can be greatly enhanced. It is not necessarily the way of salvation, although it gives life meaning and makes life bearable. Samadhi (sanskrit: ‘total self-collectedness’) is in Indian and Buddhist philosophy, religion and yoga, a state of mental concentration that unites the contemplative with the highest reality. Mircea Eliade says:

It would be wrong to regard this mode of being of the Spirit as a simple “trance” in which consciousness was emptied of all content. Nondifferentiated enstasis [contemplation of one’s own self] is not “absolute emptiness.” The “state” and the “knowledge” simultaneously expressed by this term refer to a total absence of objects in consciousness, not to a consciousness absolutely empty. For, on the contrary, at such a moment consciousness is saturated with a direct and total intuition of being. […] It is the enstasis of total emptiness, without sensory content or intellectual structure, an unconditioned state that is no longer “experience” (for there is no further relation between consciousness and the world) but “revelation.” Intellect (buddhi), having accomplished its mission, withdraws, detaching itself from the purusha and returning into prakrti. The Self remains free, autonomous; it contemplates itself. “Human” consciousness is suppressed, that is, it no longer functions: its constituent elements being reabsorbed into the primordial substance. (Eliade, 1958, p. 93)

A “total intuition of being” is the closest we can get to God, because God is the fullness of being. Everything else is to a different degree reduced in being, explains Augustine. Samadhi could be understood as a state of contemplation that amplifies unity of consciousness to a unity of cosmic dimensions. In Eastern philosophy it is generally regarded as a way of salvation; but in a Christian understanding it cannot bring personal salvation. It would be a way of achieving wholeness; of leading a holy life on earth. It’s a way of supporting God in his redemptive work. As life’s necessities take precedence, it should not go to excesses.

© Mats Winther, 2021.

References

Aquinas, St. Summa Theologica. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. (here)

Augustine, St. De Trinitate in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, Vol. 3. Philip Schaff (ed.). Christian Literature Publishing, 1887. (New Advent) (here)

Damasio, A. R. (1994). Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. Avon Books.

Eliade, M. (1958). Yoga – Immortality and Freedom. Routledge & Keegan Paul Ltd.

Feldman Barrett, L. & Salovey, P. (eds.) (2002). The Wisdom in Feeling: Psychological Processes in

Emotional Intelligence. The Guilford Press.

Jung, C. G. (1977). Mysterium Coniunctionis. Princeton/Bollingen. (CW 14)

-------- (1977b). Psychological Types. Princeton/Bollingen. (CW 6)

-------- (1977c). The Symbolic Life: Miscellaneous Writings. Princeton/Bollingen. (CW 18)

-------- (1978). Civilization in Transition. Princeton/Bollingen. (CW 10)

-------- (1981). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Princeton/Bollingen. (CW 9i)

Leuzinger-Bohleber, M. (2016). ‘Struggling with unconscious, embodied memories in a third psychoanalysis with a

traumatized patient recovered from severe poliomyelitis – A dialogue between psychoanalysis and embodied cognitive science’ in Leuzinger-Bohleber, M., Arnold, S., Solms, M. (eds.) (2016). The Unconscious – A bridge between psychoanalysis and cognitive neuroscience. Routledge.

Percy, N. & M. (2019). The Nature Of Intuition: Understand & Harness Your Intuitive Ability. Sixth Sense Books.

Solms, M. & Turnbull, O. (2002). The Brain and the Inner World. Karnac Books.

Solms, M. (2015). ‘Thinking and feeling: what’s the difference?’. FutureLearn. (here)

-------- (2016). ‘ “The unconscious” in psychoanalysis and neuroscience – An integrated approach to the cognitive unconscious’ in Leuzinger-Bohleber, M., Arnold, S., Solms, M. (eds.) (2016). The Unconscious – A bridge between psychoanalysis and cognitive neuroscience. Routledge.

-------- (2021). The Hidden Spring. Profile. Kindle Edition.

Treiger, A. (2012). Inspired Knowledge in Islamic Thought – Al-Ghazali’s theory of mystical cognition and its Avicennian foundation. Routledge.

Winther, M. (2019). ‘Modern metaphors for the Trinity’. (here)

Wundt, W. M. (1907). Outlines of Psychology. Nalanda Digital Library. (here)

Zajonc, R. B. (1980). ‘Feeling and thinking: Preferences need no inferences’. American Psychologist, 35(2), 151–175. (here)