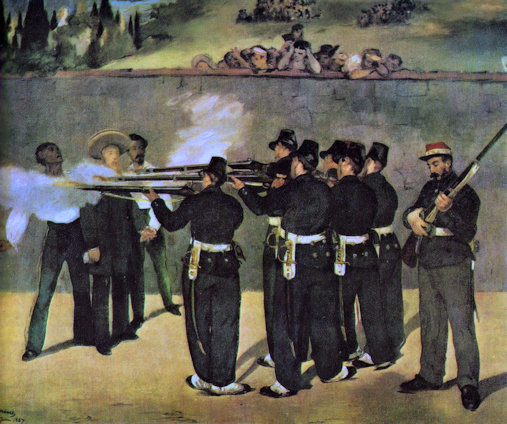

“The Execution of Mexican Emperor Maximilian”. Édouard Manet (1867).

Abstract: Group narcissism denotes the pathological version of the way in which individuals mirror themselves in a group, often associated with an idealized person. It comes to expression in religious or political extremism and in the celebrity media machine. The notions of a ‘healthy narcissism’ and a ‘natural narcissistic spectrum’ are criticized. The causes of narcissism are discussed.

Keywords: group psychology, popular culture, idols, narcissistic spectrum, mirror effect, NPD, idealization, primary narcissism, Pinsky, Fromm, Freud.

Collective narcissism

The term ‘group narcissism’ was coined by Erich Fromm in a book entitled

The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness (1973). It has an offshoot in the term

‘corporate narcissism’, referring to the business world (cmp. the recent

financial frauds in the U.S.). The dynamics of group narcissism is a destructive

factor in all human enterprise. It is a psychological phenomenon that is extremely costly to society

and to industrial companies. Incalculable sums of money are being wasted in

projects that are going on the rocks simply because the working team has

alienated itself from reality under a narcissistic leader whose postulates

cannot be questioned. Vulgar notions, such as ‘arse licker’, ‘bumsucker’, and ‘ass

kisser’, are quite apt in this context. The notion actually has its origin

in historical reality. The knights of Christianity used to prove their

submissiveness to the Pope by kissing his bottom. Fromm writes:

Most persons are not aware of their own narcissism, but only of those of its manifestations which do not overtly reveal it. Thus, for instance they will feel an inordinate admiration for their parents or for their children, and they have no difficulty in expressing these feelings because such behavior is usually judged positively as filial piety, parental affection, or loyalty; but if they were to express their feelings about their own person, such as “I am the most wonderful person in the world,” “I am better than anyone else,” etc., they would be suspected not only of being extraordinarily vain, but perhaps even of not being quite sane. (Fromm, 1992, p. 202)

The strategy of providing for one’s own narcissism by way of reflection in another ‘ideal person’, is well-known in studies of personal narcissism. In group narcissism we see a parallel phenomenon: an unquestioning loyalty and admiration for the group and its ideals, and an intense fervour in the persecution of any person who questions the authority of the overarching ideals of the group.

Now, as Fromm explains, “[an] individual, unless he is mentally very sick, may have at least some doubts about his personal narcissistic image. The member of the group has none, since his narcissism is shared by the majority” (ibid., p. 204). So here we see the reason why narcissistic individuals show a tendency to gather together in groups: it works as protection and amplification of their own narcissism. Although one would expect the narcissist to be ‘above’ such social conformity, it often represents a stepping up of his pathology. It is also gratifying to the weak and untalented narcissist since he becomes a giant by belonging to the group.

Of course, there is nothing wrong in feeling proud of belonging to a certain group. This is not narcissism. (I find the notion of a “healthy narcissism” both vulgar and theoretically improper.) Nor is there anything wrong in showing appreciation for great personalities and their work. But if we look upon Freud, Mao Zedong, or whomever, as an unquestionable authority, then we are falling prey to narcissistic idealization. If the social group is perceived as a sphere of perfect cleanliness, void of the “destructive influence” of independent thinkers, then we have become part of the narcissistic group.

Narcissistic idealization is often mistaken for a natural and healthy form of appreciation of other people. This is a great problem, as pathology is allowed to hide behind a respectable mask. It’s the same thing with group narcissism. Its devotees are often mistaken for nice fellows, who are socially mature and respectful towards other people. Nothing could be further from the truth. It is a chimera. Such people are only providing for their own narcissism by way of reflection in the group. Scratch on the surface, and a nasty intolerance appears. Many psychologists tend to view the social group as an ideal for the individual to attain. It’s an oversimplification. They are blind to the fact that there is a pathological version of social life called group narcissism.

In religious congregations the pathological fervour, building on narcissistic idealization, is often viewed as exemplary. Common among healthy people is that they do have religious faith, and that they do subscribe to ideas of great thinkers. It is a great problem that such an attitude, which is beneficial to psychic health, is, on the surface, so easy to confuse with the severe pathology of group narcissism.

Many narcissists, and individuals of ‘borderline pathology’, do not quite differ between outer and inner reality. Any formulation of outer reality is also a formulation of oneself. This is the well-known narcissistic short circuit. The subject’s personal feelings and perceptions must always be regarded as being on the same level of objectivity as anything else. An ego that is blown out of proportion and expands into outer reality cannot stand criticism. This is because anything that the subject produces, whether thoughts or anything else, remains part of the ego. He defines the world on his own, which means that he doesn’t really need to differ between subjectivity and objectivity. If the subject is angry with Mr. Smith, this also proves that he must be right because otherwise he wouldn’t have these feelings. So everybody else must also be displeased with Mr. Smith, otherwise they will be violating his world picture; in effect, they are offending his ego. So, in this situation, we have begun building a narcissistic group.

In historical times, the narcissistic group had clearly less survival value, due to bad adaptation to reality and repression of independent thinking. Historical culture had a remedy against narcissism: an unassuming view of the human personality, set against the backdrop of all the powerful spirits of nature to whom man must bow down. This gave rise to a healthy and modest ego that kept within its own confines. In today’s society the pre-scientific worldview is in decline and narcissism is on the increase.

Also gone are the natural dangers posed to the narcissistic group. In our

rich world, such people have no problems surviving. Thus, it is no longer vital to remain

adapted to reality. Corporate narcissism is funded for by our rich combines, and

by our wealthy societies. It might seem questionable to use this notion in such a

broad context as this, but, as Fromm explains, its importance has been

miscalculated. Its relevance for the neurotic personality is enormous.

Famous for being famous

In his book The Mirror Effect (2009), Drew Pinsky argues that the levels of narcissistic behaviour in our culture appear

to be at an all-time high. It’s a cultural virus, not the least driven by celebrities who as a group tend to

suffer from unhealthy levels of narcissism. A whole host of narcissistic traits — extreme self-importance, inflated

sense of specialness, vanity, envy, and entitlement — come

into play in “diva shows” (cf. Pinsky, 2009, p. 65). It has to do with the fact that outrageous behaviour tends to reinforce our sense that they belong to an exclusive group, since they can “get away with” it. Often and many times it only serves to elevate their status.

Our work suggests that contemporary culture has become fixated on a group of stars whose narcissistic tendencies appear to be approaching personality-disorder levels. This theory raises disturbing questions, especially for those of us who worry about the examples these celebrities are setting for our children. The celebrity lifestyle has become a subject of aspiration for the rest of us […]

Narcissistic celebrities whose hypersexuality, body image issues, substance abuse, or other extreme behaviors are paraded in the public square are certainly “modeling” behavior to their fans, making it seem more normal and appropriate, and encouraging others to emulate it themselves […]

The phenomenon we call the Mirror Effect has troubling implications for society at large. (Pinsky, 2009, pp. 14-15)

Celebrity magazines, reality TV shows, and social networking platforms on the Internet,

can feed narcissistic traits in the audience, functioning as incubators

for people who harbour narcissistic traits. The

normalizing of unhealthy behaviors — involving sex, alcohol, drugs, and uncontrolled

rage — are more and more seen as appropriate means of coming to terms with emotional issues and personal problems. Among young people, it leads to the creation of a “pseudo-self”, a false persona, which imitates the celebrity. The phenomenon is believed to have a magnifying effect on narcissistic traits, such as vanity, exploitativeness, unwarranted entitlement, low empathy, excessive ambition, grandiosity, and the ever-present need for acclaim and recognition from others. It causes damage to relationships, families, and the very fabric of society. On Pinsky’s view, we could be well on our way to creating a “culture of narcissism”.

The pathogenesis of narcissism

In order to come to grips with these developments, it is necessary to have recourse to a good theoretical understanding. This is not the case, today. The Freudian concept of narcissism was from its inception crooked, as it builds on Freud’s notion of ‘primary narcissism’ as explicated in his article, On Narcissism: an introduction (1916). Probably due to factors of group narcissism, ‘papa’ cannot be questioned. Thus, Pinsky and many of his psychoanalytic colleagues believe that “we are all born narcissists” and that the child entertains the grandiose feeling that it is the center of the universe.

Each one of us falls somewhere on the spectrum of narcissism. We are all born as complete narcissists and then, based upon our emotional development in early childhood, we arrive at our adult expression of these traits. (Pinsky, 2009, p. 107)

However, the premise that the baby’s or toddler’s self-perception is overblown (“His Majesty the Baby”) is illogical, because it has not yet developed a sense of self. There is still no demarcation zone between “me” and the outer world — everything is still a whole. Therefore it cannot have a grandiose perception of “myself”. If a baby cries because it is hungry, it doesn’t mean that it is attention-seeking, or has an inordinate sense of entitlement and views all “other” people as servants of “I myself” — the king. This is merely a projection. In fact, the baby cries because of its instincts. It has no other means of sustaining its existence. Toddlers are empathic. If you smile at them, they smile back. They are relational and soon develop empathic interaction. They are either curious or shy around people, and tend to tease out a smile from people by smiling at them. Nothing of this would occur if they were “complete narcissists”. As a matter of fact, unlike the adult narcissist, they aren’t manipulating people, but function wholly from the basis of healthy human instinct. It is high time that theorists do something about this monumental misconception. What’s more, they need to discard the view of the healthy mind as moderately narcissistic, because it is in fact a pathology of the ego. Thus, narcissism can only begin to show its ugly face when the ego has developed out of childhood wholeness.

Narcissism is generally viewed as a spectrum disorder, which means that it includes a range of conditions of varying severity. Sadly, this has given rise to the misconception that all people can be placed somewhere on a continuous spectrum of narcissism. Thus, this severely demoralizing disease has come to be regarded as essentially different than all other diseases. Comparatively, we don’t say that all people are schizophrenic to a different degree. But this is how many a psychoanalyst reasons about narcissism. They speak of “healthy levels of narcissism”. As the underlying psychology of narcissism isn’t properly understood, they have instead chosen to identify the disease with natural aspects of human psychology, such as aggression, ambition, and the feeling of gratification from receiving attention. If these come to expression to a moderate degree, the person is regarded moderately narcissistic, which is proper. Pinsky believes that popular culture has the capacity to magnify these aspects of our psychology, making people addicted to attention-seeking, etc. Thus, more and more people will raise their level of narcissism, from a “healthy level” to a malignant level.

However, this is not a correct description of narcissistic pathogenesis. In fact, if aggression is controlled, and the demand for attention is moderate, it implies that personality is safeguarded against narcissism. By analogy, if a man is in the habit of drinking half a pint each day, we can be certain that he is not an alcoholic, because he is evidently in full control of his weakness for a cold and fizzy beer and has no penchant for becoming drunk. This we can know beyond a doubt, because he has each day subjected himself to the temptation of becoming drunk. Since alcoholism is not regarded a continuous spectrum, we do not say that he is “moderately alcoholic” and therefore suffers from a “healthy level of alcoholism”, which is ever at risk of being augmented to alcoholism proper. So he can be trusted with an important assignment. However, we cannot be certain of a man who never touches alcohol.

Likewise, if a father for good reasons gives expression to anger, without ever succumbing to “narcissistic rage”, his children can feel perfectly safe with him, unlike if he harboured feelings of resentment that never come to expression. If a man paints in oils, but never receives any appreciation, he will likely feel sad. Should he receive some attention for his beautiful oils, he will be happy. This is wholly natural and has nothing to do with narcissism. Should he become addicted to attention-seeking, however, then something is wrong. But if he can handle his relative success, avoiding the spotlights when he has better things to do, then he belongs to the group of people who, probably due to constitutional factors, are vaccinated against narcissism. When the belly is full, one stops eating.

Otto Kernberg (1975), among others, has demonstrated that the prognosis of pathological narcissism is poor and therapy has little chance of success, although symptoms may improve. This wouldn’t be the case if narcissism were a mere addiction to attention-seeking, etc., in terms of Heinz Kohut’s ‘excessive narcissism’. Thus, narcissism depends on a deep-seated ‘narcissistic personality structure’, connected with a pronounced ‘ego weakness’. This invalidates the theory of a natural narcissistic spectrum (cf. Kernberg, 1975, p. 16; ch. 10, and elsewhere). On Kernberg’s view, malignant narcissism means that a radical disruption has occurred, in the form of a pathological development.

The misconception of psychoanalysis has the consequence that both psychologists and laymen see signs of narcissism everywhere. There are actually psychoanalysts that understand a fit of anger as a narcissistic symptom, when, in fact, a complete expression of personality is a sign of a healthy psychology. The healthy psyche is connected with instinct and natural human expression. Thereby the person in question has also demonstrated his/her ability to hold our human constitution in leash, without falling prey to overexcited behaviour. I think it is distasteful, as Pinsky does in some cases, to cast suspicion on certain celebrities of being narcissistic, when they are in fact only giving expression to our inherent human nature. A beautiful woman, for instance, would like to get some appreciation for her beauty, because it makes her feel better and increases her self-confidence. Cats do the same. When I at times played chess at a friends home, the cat was in the habit of placing herself at the middle of the chess board. This has nothing to do with narcissism, since the cat lacks an ego proper. It only gives expression to instinctual relatedness. After all, we had ignored the cat and left it unattended — this is not the way to treat a lady.

On the same grounds, a natural appreciation for one’s nation and ethnicity cannot be diagnosed as an expression of group narcissism. If a man loves to watch team sport events between his national team and foreign teams, it doesn’t mean that he is on the slippery slope to developing nationalistic chauvinism. We are only capable of keeping such feelings within our supervising consciousness if we connect with our inborn nature and allow them to come to expression, to a relative degree. However, the concept of a continuous spectrum of narcissism leads theorists to misinterpret expressions such as these. In fact, they are really wholly healthy and grounded in our congenital human nature. A young boy will typically see the older and stronger boy as a role model and feel admiration for him. It is wholly natural and beneficial for the growth to maturity. Why such healthy mechanisms, among some individuals, take a turn for the worse and lead to obsessive behaviour is another question. I am convinced that the malady stems from the constitutionally weak ego and a concomitant insufficiency of consciousness, corrupted by a culture incapable of leading its members on to psychological adulthood.

The conclusions from research

The doctrine of ubiquitous narcissism is a derivate of Heinz Kohut’s theory.

In contrast to traditional psychoanalysis, which focuses on drives (instinctual motivations of sex and aggression), internal conflicts, and fantasies, self psychology thus placed a great deal of emphasis on the vicissitudes of relationships. Kohut demonstrated his interest in how we develop our “sense of self” using narcissism as a model. (Wiki, here)

Fiscalini (…) suggested that narcissism is a dimension present in all people, ranging from normal to pathological, and cutting across the diagnostic spectrum with both milder and more severe forms. (Campbell & Miller, 2011, ch. 5)

This model is paradoxical because it bases human psychology on narcissism despite the fact that personality emerges from an ego-less state. As I’ve already shown, this view is not universally accepted. It conflicts with the Jungian view, and psychodynamic theory, generally. According to The Handbook of Narcissism (2011) a theoretical divide characterizes the psychology of narcissism. This comprehensive work supports the view that the narcissistic spectrum and normal psychology represent two different forms of psychic economy. In chapter 29 (‘The Emotional Dynamics of Narcissism - Inflated by Pride, Deflated by Shame’), Jessica L. Tracy et al. explain that we must distinguish narcissism from genuine self-esteem:

Our emphasis on the emotions underlying narcissism allows us to better distinguish two personality processes that are frequently confused or conflated: narcissistic self-aggrandizement (also known as narcissism, grandiose narcissism, self-enhancement, fragile self-esteem, self-deception, and nongenuine self-esteem) and genuine self-esteem […]

[A] growing body of research suggests that there is an alternative, adaptive way of experiencing self-favorability, which is empirically distinct from narcissism. Individuals who are not burdened by implicit low self-esteem and shame do not behave in the same defensive manner as individuals high in narcissism. For example, when faced with an ego threat, only individuals with dissociated implicit and explicit self-views and, specifically, low implicit and high explicit self-esteem, respond to the threat defensively and engage in compensatory self-enhancement (…). Individuals who do not show such dissociations tend to have more stable self-esteem (…), tend not to get defensive in the face of threat, and are less likely to self-enhance (…). Similarly, individuals with noncontingent self-esteem show fewer decreases in self-esteem in response to negative life events (…), and individuals high in self-esteem controlling for narcissism (i.e., genuine self-esteem) tend to be low in aggression and anti-social behaviors […]

Individuals who experience genuine self-esteem thus seem able to benefit from positive self-evaluations without succumbing to the host of interpersonal and mental health problems associated with narcissism. Genuine self-esteem allows individuals to acknowledge their failures, faults, and limitations without defensiveness, anger, or shame, and integrate positive and negative self-representations into a complex but coherent global self-concept. [Statistics reveal] starkly divergent correlations between the two partialled constructs (conceptualized as narcissism-free genuine self-esteem and self-esteem-free narcissistic self-aggrandizement) […]

Given these empirical findings, the self-evaluative system and underlying emotions that characterize individuals high in genuine self-esteem must be quite different from those that characterize narcissism. Rather than responding to success with hubristic pride, individuals high in genuine self-esteem tend to respond with authentic pride, an emotion marked by feelings of confidence, productivity, and self-worth (…). This adaptive emotional response […] is attainable because the integration of positive and negative self-representations allows for more nuanced self-evaluations. If success occurs, it need not be attributed to a falsely inflated, stable, global self; credit can instead be given to specific actions taken by the self (e.g., hard work) — an appraisal found to promote the experience of authentic and not hubristic pride (…).

Likewise, when failures occur, individuals high in genuine self-esteem need not succumb to the shame-destined attributional trap of blaming the stable, global self; negative events, too, can be attributed to specific actions. Within the context of overall self-liking, self-acceptance, and self-competence, mistakes are not self-destructive agents of demoralization, but rather can be agents of change, pointing to areas of future improvement. (Campbell & Miller, 2011, ch. 29)

The authors present a model of “self-regulatory processes underlying narcissism and associated fragile self-esteem (…), with an emphasis on the driving forces of shame and pride.”

There are “starkly divergent correlations” between the narcissistic personality and the normal personality in the most central emotional aspects of human personality. They react wholly differently to the same stimulus, whereas in the narcissistic spectrum model, they would respond similarly but with different intensity. In fact, at occasions when the narcissist reacts defensively, the normal person shows no such signs, because he has “genuine self-esteem” due to a strong ego.

Thus, constitutional ego frailty is what accounts for the characteristic traits of narcissism, such as entitlement, grandiosity, need for admiration, lack of empathy, arrogance, envy, and exploitativeness. These traits do not characterize the normal personality, not even in a weak form. After all, characteristic of the strong ego is that it has recourse to an inner source of life whereas the narcissist must rely on an outer source. Note that ego strength does not signify an overtly strong and self-assured person, being experienced in the ways of the world. Rather, Richard Sennett (1992) explains that such a person has “the integrity to be confused”. The pain can be endured because there is no risk of dissolution and regression (cf. Winther, 2003, here).

This model coincides largely with earlier literature, according to which “primary narcissism” is regarded as obsolescent, whereas the adult narcissistic strategy is viewed as a form of lingering and deep-rooted immaturity, sometimes dependent on hereditary factors.

Refutation of the natural narcissistic spectrum

Although narcissism is denoted a spectrum disorder, it doesn’t mean that all people can be placed on a narcissistic scale. Rather, it means that those who suffer from the disease can be mildly or seriously affected. Autism is also regarded as a spectrum disorder; but it doesn’t mean that all people are autistic to a degree. Yet, according to a heavily popularized theory, narcissism is a trait-based disorder that must be understood as merely a pathological amplification of narcissistic traits present in everybody. It means that all people are narcissistic to a degree.

Characteristic of narcissism is a sense of grandiosity. Yet, all people do not experience excessive feelings of self-importance “to a different degree”. Either you have inadequate feelings of self-importance or not. If you don’t, then you are not narcissistic. Another example is that narcissists tend to react to criticism with rage, since they feel humiliated. Yet, many people do not feel humiliated but are grateful for constructive critique, especially when it concerns an intellectual or artistic product.

Narcissists get a kick out of attention and admiration. In contradistinction, many people do not at all appreciate admiration. For instance, a scientist is happy when his theory receives attention. On the other hand, it is quite common that scientists dislike admiration for their person, so much so that they shy away from publicity. Moreover, narcissists readily take advantage of other people to achieve their own goals. This is unthinkable to many people. Personally, I would be capable of punching a person in the face, but I could not steal his work.

So, how do we account for this? How come some people lack a sense of grandiosity, and how can they experience the opposite feelings when they receive admiration for their person? How come they are pleased when somebody criticizes their work? Evidently, the person in question is thereby taken seriously, since he/she is being treated as an adult independent thinker, artist, or whatever, and will likely benefit from the critique.

The theory of omnipresent narcissism rules out that people can have the opposite feelings. On this view, when a person receives admiration, he/she must at least experience a tiny gratificatory feeling. When faced with critique, he/she must at least get a little humiliated and angry. Since this is not the case, there are people who cannot be placed on the narcissistic scale. The conclusion is that the theory of ubiquitous narcissism is wrong. Since we know that many people feel awkward when receiving admiration as a person, the theory collapses. This is called empiricism, and it is an indisputable principle practiced in the hard sciences. As soon as a theory confronts an empirical fact that contradicts the theory, the theory collapses.

Grandiosity and vulnerability

A person who thinks of himself as infallible and invincible is delusional and seriously ill. We are all fallible, and we keep making mistakes all the time. So, if one works as a computer programmer one is bound to make programming errors, and there’s no way around it. The best remedy is self-criticism. Only if we look at ourselves and our products with a critical eye, can we avert many mistakes. A person who suffers from delusional grandiosity has a seriously defective ego. The ego is the “reality function”. If the ego isn’t realistic anymore, then it has lost its capacity of adaptation to reality, which means that it is “weak”. Yet, this is exactly what the grandiose personality does not want to admit to himself.

Contrariwise, some psychologist characterize narcissism according to the outward expression of personality. They affirm that ego frailty is unfitting, because personality does not seem to give expression to a weak ego. Accordingly, a view has emerged which equates the grandiose form with “true” narcissism, while the vulnerable form is diagnozed as merely an immature attitude. Against this, Pincus and Roche explain that both grandiosity and vulnerability are phenotypic expressions of Pathological Narcissism — different strategies, as it were:

Narcissistic grandiosity involves intensely felt needs for validation and admiration giving rise to urgent motives to seek out self-enhancement experiences. When this dominates the personality, the individual is concomitantly vulnerable to increased sensitivity to ego threat and subsequent self-, emotion-, and behavioral dysregulation. Individual differences in the expression of narcissistic grandiosity and narcissistic vulnerability have been identified across disciplines. It is important, however, to distinguish the definition of narcissism from its diverse phenotypic expressions. For example, narcissistic grandiosity should not be defined by phenomena such as self-reported or informant-rated high self-esteem, interpersonal dominance, or low agreeableness although expressions of narcissistic grandiosity may include an inflated self-image, domineering interpersonal problems, and so on. Similarly, narcissistic vulnerability should not be defined by phenomena such as depression or borderline personality disorder, although expressions of narcissistic vulnerability may include anhedonia, social withdrawal, negative affectivity, suicidality, and so on. (Campbell & Miller, 2011, ch. 4)

There is today a tendency in psychology to confuse the symptoms with their cognitive causes; a bias present in experimental psychology. After all, experimental scientists study the outward phenomena of matter. What psychologists mustn’t forget, however, is that physicists devote much time to understanding how the material world “thinks”. The inner rules of matter must first be conceived intellectually. It is to no avail merely to collect empirical data and then jump to conclusions as to what the phenomenon means. This is especially true of human psychology. Just because a man appears forceful and self-assured on the surface, it doesn’t mean he has a strong ego. The persona is not necessarily a truthful reflection of the inner world.

If we reason in that way, we promote a superficial view of human nature.

The Western tradition of inwardness, inaugurated by St Augustine, has stimulated the acquirement of an inner locus of control (Wiki, here). It allows us to control our destiny and opens up the possibility of self-understanding and self-critique. On this view, our private world, separate from the intelligible world, is more relevant than outward symptoms and behaviours. Our psychological nature is characterized by interiority, subjectivity, and inwardness. In so far as psychology focuses on outwardness, it does not take our true nature into account.

There is, however, a variant that differs from pathological narcissism (NPD), namely the puer aeternus or Peter Pan syndrome (cf. Winther, 2015, here). It could also be called puerile narcissism. On the surface, it is more endurable for the social environment. The puer aeternus neurosis has been thoroughly investigated by several psychoanalysts. It is reminiscent of the phenomenon of juvenilization among domesticated animals, who never acquire an adult psychology. It has been suggested that humankind goes through such a process of psychological neoteny (retention in adults of juvenile traits). It is further hastened by the increase of the welfare society. In the process we lose contact with instinct. Arguably, it is this process that Pinsky and Young have observed, and which they call the “mirror effect”.

© Mats Winther, 2004-2018.

References

Campbell, W. K. & Miller, J. D. (eds.) (2011). The Handbook of Narcissism and Narcissistic Personality Disorder. Wiley.

Freud, S. (1999). ‘On Narcissism: an introduction’ (1916). The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, vol. 14. Vintage.

Fromm, E. (1992). The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness. Holt Paperbacks.

‘Heinz Kohut’. Wikipedia article. (here)

Kernberg, O. (1975). Borderline Conditions and Pathological Narcissism. Jason Aronson.

‘Locus of control’. Wikipedia article. (here)

Pinsky, D. & Young, S. M. (2009). The Mirror Effect – How Celebrity Narcissism is Seducing America. Harper Collins.

Sennett, R. (1992). The Uses of Disorder: Personal Identity and City Life. W. W. Norton. (1970).

Winther, M. (2003). ‘Winnicott’s Dream – A Critique of Winnicott’s Thought as a Form of Mystical Narcissism’. (here)

---------- (2015). ‘The Puer Aeternus – underminer of civilization’. (here)

See also:

Saedi, G. A. (2013). ‘Is Celebrity Behavior Making You a Narcissist?’. Psychology Today. (here)

Winther, M. (2011). ‘Mysterium Iniquitatis – The mystery of evil’. (here)

Young, S. M. & Pinsky, D. (2006). ‘Narcissism and celebrity’. Journal of Research in Personality, 2006. (here)